Wrth ddysgu neu wella ein dealltwriaeth o’n hiaith, mae angen cefnogaeth a chymorth oddi wrth bobl eraill arnom, pobl sydd wedi’i meistroli ac sydd gyda’r sgiliau i’w hesbonio’n effeithiol. Yma, mae Mark Stonelake, sydd wedi ysgrifennu llyfrau cwrs i CBAC a Dysgu Cymraeg - Ardal Bae Abertawe, wedi cytuno i rannu ei ddoethineb gyda'r byd. Mae parallel.cymru yn ei gyflwyno fe ar ffurf cwestiynau ac atebion, gyda thabl cynnwys isod.

When learning or improving our understanding of a language we need support and help from others who have mastered it and are skilled at explaining it to others. Here, Mark Stonelake, who has written course books for the WJEC and Learn Welsh- Swansea Bay Region, has kindly agreed to share his wisdom with the world. Parallel.cymru presents it in the form of questions and answers, with a table of contents below.

Mae Mark yn dod o Aberdâr yng nghymoedd de Cymru. Ar ôl ennill gradd yn y Gymraeg ac wedyn gwneud addysg Gymraeg ran-amser yn y 1980au, dechreuodd Mark weithio fel tiwtor a threfnydd llawn amser ym 1993, gan arbenigo mewn datblygu, trefnu a dysgu cyrsiau Cymraeg dwys iawn. Roedd Mark yn Swyddog Cwricwlwm ac Adnoddau yng Nghanolfan Cymraeg i Oedolion De-orllewin Cymru o 2006 i 2016. Roedd e'n Rheolwr Datblygiad Proffesiynol ac Ansawdd o 2016 i 2018 yng Nghanolfan Dysgu Cymraeg Ardal Bae Abertawe yn Academi Hywel Teifi, Prifysgol Abertawe. Yn ogystal â datblygu cyrsiau yn Abertawe, fe a gyd-ysgrifennodd gwrslyfr CBAC Sylfaen. Mae e wedi ymddeol o weithio lawn amser ers cynnar 2018 ond mae e'n dal i weithio mewn addysg ran-amser.

Mark is from Aberdare in the South Wales Valleys. After doing a degree in Welsh and working part-time teaching Welsh in the 1980s, Mark started as a full time tutor/organiser in 1993, specialising in developing, organising and teaching highly intensive Welsh courses. From 2006 to 2016 he was appointed as the Curriculum and Resources Officer in the South-West Wales Welsh for Adults Centre. From 2016 to 2018 he was the Personal Development and Quality Manager at the Learn Welsh Swansea Bay Area centre in Academi Hywel Teifi at Swansea University. In additon to developing courses in Swansea, he co-wrote the WJEC Foundation course book. He retired from working full time in early 2018 but continues to teach part-time.

Nodyn am y geirfa wedi'i chyflwyno yma: Yma ac acw, mae rhai o'r geiriau'n fwy addas eu defnyddio gan ddysgwyr yn Ne Cymru na chan ddysgwyr y Gogledd. Fodd bynnag mae cysyniadau gramadegol yn gwmwys i bob tafodiaith Gymraeg.

A note on the language: Some of the vocabulary was written for learners in South Wales, but the grammar concepts are applicable to all Welsh dialects.

Nodyn ar sut mae'r gramadeg wedi'i gyflwyno: Mae'r defnydd yma wedi'u hysgrifennu ar gyfer dysgwyr sydd yn gwneud cyrsiau dros 4 - 10 o flynyddoedd. Felly, os bydd dysgwyr newydd yn gweld popeth yn yr un lle ac ar yr un pryd, efallai y byddan nhw wedi eu llethu ganddo fe. Dylai dysgwyr ddefnyddio'r defnydd yma i gefnogi ffurfiau eraill o ddysgu. Er enghraifft, byddan nhw'n gallu defnyddio'r ganllaw hon dros sawl blwyddyn i ddod o hyd i esboniadau amgen ac er mwyn egluro pynciau. Fe fydd hefyd yn rhoi cymorth i bobl sydd eisoes yn medru'r Gymraeg ac sydd eisiau cryfhau eu gwybodaeth, a gloywi eu deallwriaeth greddfol.

A note on the presentation: This content was designed to be delivered to learners over the course of 4-10 years, and new learners receiving this all in one place could feel overwhelmed. Its purpose is to support an existing learning method, and for this guide to be referred to as a reference, clarification and alternative explanation over a number of years. It is also helpful for people with a good knowledge of Welsh to reinforce and clarify their intuitive understanding.

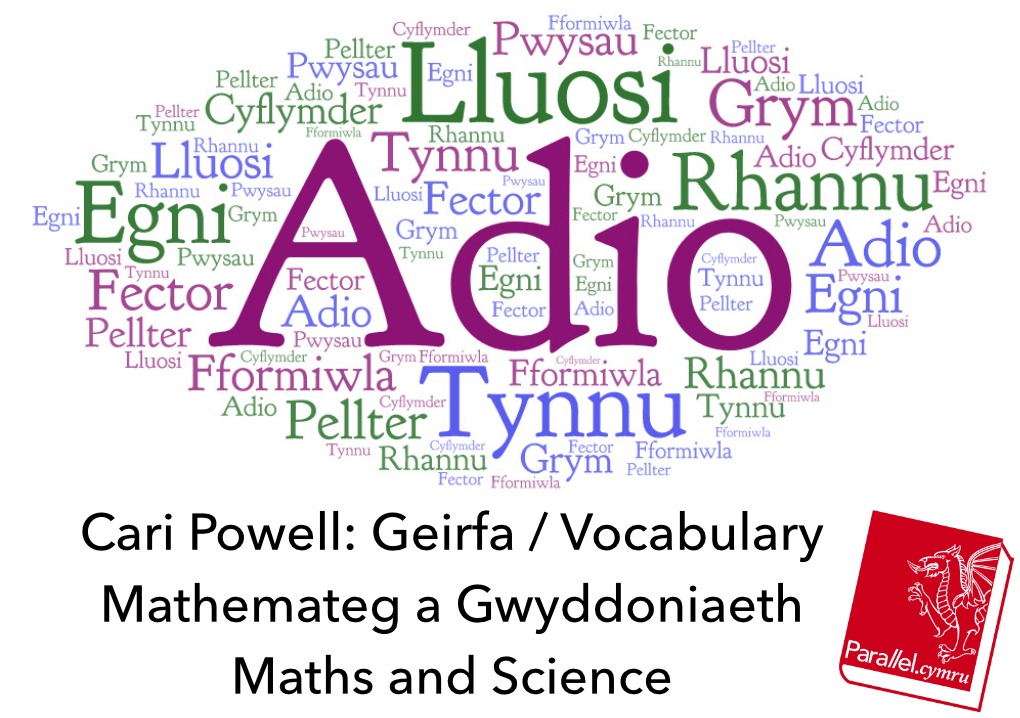

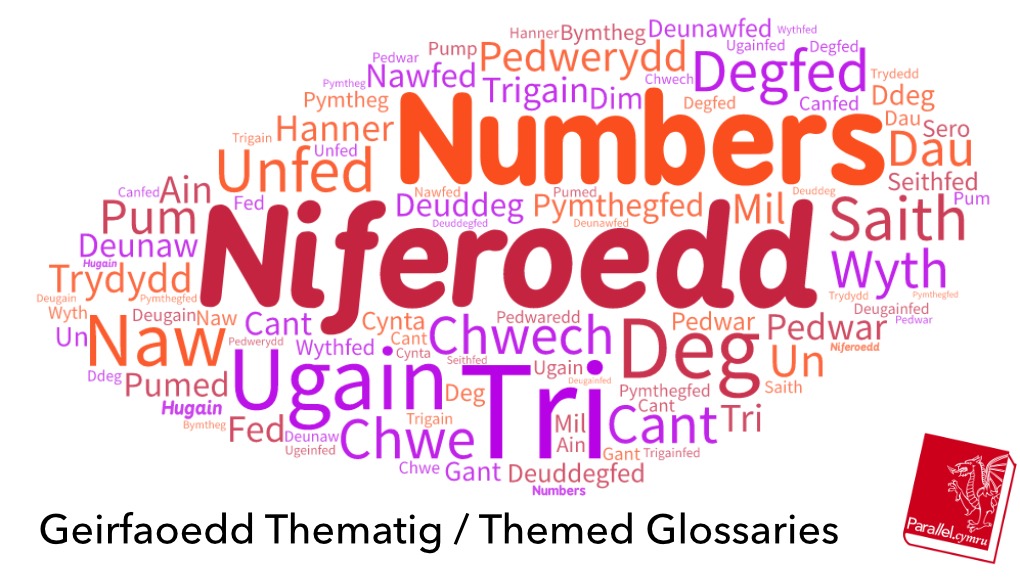

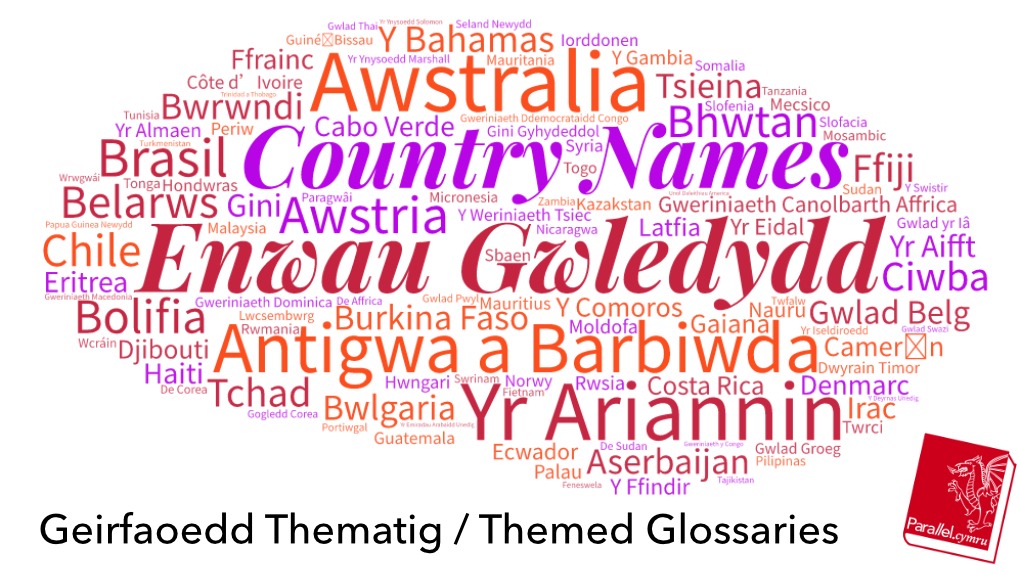

Rhagor o enghreifftiau: Mae enghreifftiau a delweddau ychwanegol gyda'r symbol * wedi cael eu paratoi gan Patrick Jemmer a Neil Rowlands i parallel.cymru. Er moyn cadw'r delweddau, right-click/long-press ac wedyn dewiswch 'Save As'.

Yn ychwanegol, diolch yn fawr i Patrick Jemmer am gyfieithu’r darnau gramadeg i’r Gymraeg ac y prawf ddarllenwyr am eu hawgrymiadau nhw.

More examples: The extra examples and images with the * symbol have been prepared by Patrick Jemmer and Neil Rowlands for parallel.cymru. In order to save the images, right-click/long-press and then choose 'Save As'.

In addition, thank you very much to Patrick Jemmer for the English to Welsh translation and to the proof readers with their suggestions.

Lefel Mynediad / Entrance Level

| Termau Gramadeg Beth yw ystyr y termau sylfaenol mewn gramadeg, fel berfau, enwau ac ansoddeiriau? | Grammar Terms What are basic grammar terms such as verbs, nouns and adjectives? |

| Yr Wyddor Sut mae'r wyddor yn wahanol yn y Gymraeg, a sut mae'n cael ei hynganu? | The Alphabet How is the alphabet different in Welsh and how is it pronounced? |

| Ti & Chi Pryd y dylwn i ddefnyddio Ti a phryd dylwn i ddefnyddio Chi? | Ti & Chi When should I use Ti and when should I use Chi? |

| Adeiladwaith brawddegau / Trefn geiriau Sut mae trefn y geiriau yn y Gymraeg yn wahanol i'r drefn yn Saesneg? | Sentence structure / Word order How does the order of words in Welsh differ from that in English? |

| Enwau ag Ansoddeiriau a Rhifau Sut mae enwau'n cael eu defnyddio gydag ansoddeiriau a gyda rhifolion? | Nouns with Adjectives and Numbers How are nouns used with adjectives and numbers? |

| Cyflwyno Treigladau Mae treigladau'n un o nodweddion arbennig yr ieithoedd Celtaidd, sy'n helpu sŵn yr iaith i lifo'n rhwydd. Pa synau sydd yn newid, a beth sy'n achosi'r newidiadau? | Introducing Mutations One of the unique characteristics of the Celtic languages, mutations help the sound of the language to flow smoothly. Which letters change and what are the main changes? |

| Fe / Hi, Yn / Mewn & Y / Yr Ar adegau, y geiriau byrraf sy'n achosi'r problemau gwaethaf. Sut, yn union y mae'r Gymraeg yn trin Fe/Hi, A/An, Yn/Mewn ac Y/Yr? | It, A / An, In & The Sometimes the shortest words can give the biggest problems. Precisely how does Welsh deal with Fe/Hi, A/An, Yn/Mewn and Y/Yr (It, A/An, In and The)? |

| Y tri math o Yn Mae'r gair Yn yn cael ei ddefnyddio mewn tair ffordd wahanol- beth ydyn nhw? | The three types of Yn The word Yn is used in three different ways- what are these? |

| Mae, Oes & Ydy Pryd y dylech chi ddefnyddio Mae, Oes ac Ydy? Mae hyn yn gallu achosi penbleth. Beth yw'r ateb? | Mae, Oes & Ydy When to use mae, oes and ydy can cause confusion- when do we use which one? |

| Cyflwyno'r amser gorffennol - Es i / I went Sut gallwn ni ddechrau defnyddio berfau cryno’r gorffennol i ddweud pethau fel 'I went'? | Introducing the past tense - Es i / I went How do we start using the past tense and saying things like 'I went'? |

| Cyflwyno'r amser gorffennol (parhad) - Defnyddio 'Gwneud' Sut gallwn ni ddefnyddio'r gorffennol cryno i ddweud 'I did' hefyd? | Introducing the past tense (continued) - Using 'Gwneud' How do we extend the past tense by saying 'I did'? |

| Defnyddio berfau yn yr amser gorffennol Sut mae gweddill y berfau'n rhedeg yn yr amser gorffennol? | Using verbs in the past tense And what are the rules for the rest of the past tense verbs? |

| Yr amser gorffennol (Cael) Sut gallwn ni ddefnyddio’r amser gorffennol i ddweud 'I had' hefyd? | The past tense (Cael) How do we extend the past tense by saying 'I had'? |

| Yr amser gorffennol (Dod) Sut gallwn ni ddefnyddio’r amser gorffennol i ddweud 'I came' hefyd? | The past tense (Dod) How do we extend the past tense by saying 'I came'? |

| Rhagenwau Personol- Fy, Dy, Ei ayyb Mae treiglo'n digwydd pan fydd rhagenwau'n cael eu defnyddio gydag enwau a berfenwau. Beth sy'n newid? | Personal Pronouns- How to say ‘my’, ‘your’, ‘his, ‘her’, etc When we relate a noun or verb to a person some mutations take place. What changes? |

| Gallu, Moyn & Eisiau Beth yw'r gwahaniaeth rhwng Gallu, Moyn ac Eisiau? Pam mae Moyn ac Eisiau yn gweithio'n wahanol i'w gilydd? | Gallu, Moyn & Eisiau What is the difference between Gallu, Moyn and Eisiau, and why do Moyn and Eisiau behave slightly differently? |

| Cyn, Ar Ôl & Wedyn Pryd y dylen ni ddefnyddio Cyn a phryd y dylen ni ddefnyddio Ar ôl neu Wedyn? | Cyn, Ar Ôl & Wedyn When should we use Cyn and when should we use Ar ôl or Wedyn? |

| Y Ferf 'Bod' Yn y Gymraeg mae berfenw 'Bod / To Be' yn hyblyg iawn, ac mae ganddi lawer o ffurfiau. Beth ydyn nhw? | The Verb To Be The verb 'To Be / Bod' is very pliant in Welsh, and takes on many forms. What forms does it take? |

| Berfau Cryno Trwy ddefnyddio'r rhain, rydyn ni'n gallu dweud pethau mewn llai o eiriau. Sut mae gwneud hyn? | Short Form Verbs These allow us to condense an action into a shorter expression. How can we do this? |

| Wedi Beth yw ystyr y gair Wedi, a sut mae ei ddefnyddio? | Wedi What does the word Wedi mean, and how should we use it? |

| Rhaid i fi Sut mae mynegi rhaid neu angen? | Rhaid i fi- I have to / I must How do we express a necessity or need? |

| Arddodiaid Dyma grŵp o eiriau sy'n golygu 'to, on, at' etc. Sut mae dewis pa un i ddefnyddio gyda berf os bydd angen un? | Prepositions There are a range of words which equate 'to on, at', etc. How do we know which one to use with which verbs? |

| Ateb Cwestiynau Dyw ymateb i gwestiynau yn y Gymraeg ddim cyn hawsed ag y mae yn y Saesneg. Beth yw'r dewisiadau? | Answering yes and no Responding to questions isn't quite as simple as in English. What are our answer options? |

| Cyflwyno’r Amherffaith Sut mae dweud beth yr oedden ni ei wneud yn y gorffennol? | Introducing the Imperfect Tense How do we say what we were doing in the past? |

| Cyflwyno Gorchmynion Sut mae dweud pethau fel Go! Get ...! Be...! ac yn y blaen? | Introducing Commands How do we say things like Go! Get...!, Be...! and so on... |

| Ffurfio gorchmynion Sut mae defnyddio gorchmynion gyda mwy o ferfau? | Command Endings How do we use commands with a wider range of verbs? |

| Mynd â & Cymryd Pryd mae defnyddio Mynd â, a phryd mae defnyddio Cymryd? | Mynd â & Cymryd- To Take When do we use each form of Mynd â and Cymryd? |

| Bydd- Amser dyfodol Bod Sut mae dweud pethau fel 'I will be there at 7'? | Bydd- the future tense of Bod (to be) How do we say things like 'I will be there at 7?' |

| Sydd- Ffurf arall ar amser presennol 'Bod' Pan fyddwn ni eisiau dweud 'who is/are’ or ‘which is/are' yn yr amser presennol, bydd rhaid defnyddio Sydd. Sut mae hyn yn gweithio? | Sydd- Another form for the present tense of 'Bod / To Be' When we want to use the present tense with 'who is/are’ or ‘which is/are' we need to use Sydd- how does this work? |

| Defnyddio Gallu yn yr amser dyfodol Sut mae dweud pethau fel 'I can', 'Can I', 'Yes you can' a 'No you can't'? | Using Gallu in the future tense How do we say things like 'I can', 'Can I', 'Yes you can' and 'No you can't'? |

| Hwn, Hon, Hwnna, Honna, Y Rhain & Y Rheina Mae ffurfiau'r geiriau sy'n golygu This, That, These and Those yn debyg iawn yn y Gymraeg- ydych chi'n gallu esbonio p'un yw p'un? | This, That, These and Those The forms of This, That, These and Those are very similar in Welsh- can you you explain which is which? |

| Sut, Pa Mor & Pa Pa eiriau rydyn ni'n eu defnyddio mewn cwestiynau fel 'How are you?', 'What kind of house is it?' and 'What colour is it?'' | Sut, Pa Mor & Pa Which forms do we use for questions such as 'How are you?', 'What kind of house is it?' and 'What colour is it?' |

Lefel Sylfaen / Foundation Level

| Cyflwyno'r Amser Dyfodol Sut mae dweud pethau fel 'Will you get up?' and 'Will you pay?' yn yr amser dyfodol? | Introducing the future tense How do we say things like 'Will you get up?' and 'Will you pay?' in the future tense? |

| Adolygu arddodiadau a'r terfyniadau priodol Rywbryd byddwn ni'n gweld pethau fel 'arno fe' and 'amdani hi'- beth yw'r ymadroddion yma, a beth yw'r patrymau sylfaenol? | Recapping prepositions and adding endings Sometimes we see things like 'arno fe' and 'amdani hi'- what are these and the patterns behind them? |

| Cyflwyno Bod fel That Yn aml yn y Saesneg byddwn ni'n gadael y gair 'that' allan o frawddegau, ond dyw hyn ddim yn bosibl yn y Gymraeg. Sut mae cyfleu ystyr y gair 'that'? | Introducing Bod as That In English we often omit 'that' from sentences, but this isn't possible in Welsh. How do we convey 'that'? |

| Cymalau yn yr amser dyfodol Beth sy'n digwydd pan fyddwn ni'n siarad am y dyfodol? | Clauses with the future tense What happens with 'bod' when we talk about the future? |

| Cip arall ar yr amser dyfodol Sut mae defnyddio Mynd, Cael a Gwneud i ofyn cwestiynau ac i ffurfio brawddegau negyddol? | Taking a look at the future tense again How do we form questions, use negatives and mynd, cael and gwneud? |

| Mwy am yr amser dyfodol Dyma ni'n gweithio'n galed iawn i ddysgu am yr amser dyfodol -- gawn ni ymarfer y terfyniadau rheolaidd? | Extending the future tense We are covering a lot of the future tense here- can we recap the straightforward regular endings? |

| Gofyn cwestiynau yn yr amser dyfodol Sut mae gofyn cwestiynau fel 'Will you learn? or 'Will they see?' | Asking questions in the future How do we ask questions such as 'Will you learn? or 'Will they see?' |

| Yr amser dyfodol (Cael) Sut mae dweud pethau fel 'I’ll have' a 'May I have?' | The future tense of Cael How do we say things such as 'I’ll have' and 'May I have?' |

| Yr amser dyfodol (Dod) Gan fod Dod yn afreolaidd yn yr amser dyfodol, sut mae defnyddio'r ffurfiau yma? | The future tense of Dod As Dod is irregular in the future, how do we use these forms? |

| Cyflwyno'r Goddefol Sut mae dweud pethau sy wedi digwydd i ni, fel 'I was born' neu 'She was brought up'? | Introducing the Passive voice How do we say things that have happened to us, such as 'I was born' or 'She was brought up'? |

| Mynegi hoffter gan ddefnyddio 'Mae'n well gyda fi' Sut mae dweud pethau fel 'I prefer...' neu 'What do you prefer?' ...? | Expressing a preference with 'Mae'n well gyda fi' How do we say things like 'I prefer...' or 'What do you prefer?' |

| Cyflwyno'r Amodol Sut mae dweud pethau fel 'I would be' a 'They would go'? | Introducing the Conditional tense How do we say things like 'I would be' and 'They would go'? |

| Yr Amodol (parhad)- If I Could Sut mae dweud pethau mwy cymhleth gan ddefnyddio'r amodol fel 'If I was to go?' | Continuing the Conditional tense with If I Could How do we extend the conditional tense and express a touch more complexity with things like 'If I was to go?' |

| Cyflwyno Rhifolion a Threfnolion Sut mae dweud pethau fel 'the first, second or twenty-third'? | Introducing Cardinal and Ordinal numbers How do we say things like the first, second or twenty-third? |

| Cyflwyno Gorchmynion- gyda Ti Sut mae dweud pethau fel ''Stand up' neu 'Don't'...? | Introducing Commands- with Ti How do we say things like 'Stand up' or 'Don't'... |

| Y Goddefol (parhad) Cip arall ar y goddefol | Continuing the Passive voice Taking another glance at the Passive voice |

| Mor, Cystal & Cynddrwg Sut mae dweud 'So', 'As...as', 'As good as' ac 'As bad as'? | Mor, Cystal & Cynddrwg How do we say 'So', 'As...as', 'As good as' and 'As bad as'? |

| Cymharu dau beth Beth yw'r patrwm sylfaenol pan fyddwn ni'n dweud pethau fel 'Wetter', 'Taller' and 'Younger'? | Comparing two things What is the pattern behind saying things like 'Wetter', 'Taller' and 'Younger'? |

| Cymharu Ansoddeiriau Mae patrymau rheolaidd i'w defnyddio pan fyddwn ni'n cymharu pethau, er enghraifft pan fyddwn ni'n dweud "Mae Eglwys Gadeiriol Llandaf yn dalach na Neuadd y Ddinas ond Stadiwm y Mileniwm yw'r adeilad tala". Beth yw'r rhestr lawn? | Comparison of Adjectives There are set patterns for comparing items, for example saying "Mae Eglwys Gadeiriol Llandaf yn dalach na Neuadd y Ddinas ond Stadiwm y Mileniwm yw'r adeilad tala". What is the full list? |

| Cymharu ansoddeiriau- Y Radd Eithaf Sut mae dweud pethau fel 'The tallest', 'The biggest' neu 'The wettest'? | Comparing two adjectives- The Superlative How do we say things like 'The tallest', 'The biggest' or 'The wettest'? |

| Cymalau: Tair ffordd o ddweud That- Taw, Y & Bod Pryd y dylech chi ddefnyddio Taw, Y & Bod, y tri ohonyn nhw sy'n golygu 'that'? | Clauses: Three ways of saying That- Taw, Y & Bod How do we know when to use Taw, Y & Bod where they each mean 'that'? |

| Dylwn Sut mae cychwyn dweud pethau fel 'I should go'? | Dylwn- I should How do we get started with saying things such as 'I should go'? |

| Geiriau llenwi- Sut mae cael amser i feddwl wrth siarad? Beth dw i'n gallu ei ddweud i lenwi bwlch wrth i fi lunio'r frawddeg nesaf? | Verbal fillers- giving you time to think when speaking What can I say to fill a gap while I'm still putting the next sentence together? |

| Cyflwyno Berfau Cryno Rywbryd rydyn ni'n clywed ymadroddion fel 'Licwn i fynd' ac 'Allet ti?'- sut mae'r rhain yn cael eu llunio? | Introducing short-form verbs Sometimes we hear expressions such as 'Licwn i fynd' and 'Allet ti?'- how are these formed? |

| Heb - Mae'r gair yma yn cael ei ddefnyddio i olygu 'without' a hefyd i olygu 'Ddim wedi' Sut mae defnyddio Heb i olygu 'without' neu i olygu 'ddim wedi'? | Heb- Used as 'without' and in place of 'Ddim wedi' to mean 'have not' How do we go about using Heb in its two different forms? |

| Wrth Fy Modd Beth yw ffurfiau eraill yr ymadrodd 'Wrth fy modd', sy'n golygu 'I am delighted'? | Wrth Fy Modd- In my element or Delighted What are the variations of 'Wrth fy modd', meaning 'I am delighted'? |

| Ar ôl, Ar bwys, O flaen & O gwmpas Mae geiriau yma yn eithaf tebyg i'w gilydd- Beth yw'r gwahaniaeth rhyngddyn nhw? | Ar ôl, Ar bwys, O flaen & O gwmpas - After, Beside, In front of & Around These sets of words can sound quite similar- what is the difference between them? |

| Bod yn yr Amodol: Byddwn, Byddet, Byddai, Bydden, Byddech, Bydden Sut mae cychwyn dweud pethau fel 'I would go' a 'She would come'? | The conditional form of Bod: Byddwn, Byddai & Byddet How do we start saying things such as 'I would go' and 'She would come'? |

| Cyflwyno Lluosog Enwau Beth yw rhai ffyrdd o ffurfio lluosog enwau yn y Gymraeg? | Introducing plurals What are some ways in which plurals are formed in Welsh? |

| Dim Ond Beth yw ystyr yr ymadrodd 'Dim ond' a sut mae'n effeithio'r frawddeg o'i gwmpas? | Dim Ond- Only What does 'Dim Ond' mean and how does it affect the sentence around it? |

| Pwysleisio rhannau brawddeg yn yr amser presennol ac yn yr amser gorffennol Sut mae newid brawddeg i bwysleisio rhan wahanol ohoni hi? | Emphasising elements of a sentence in the present and past tense How do we amend a sentence to emphasise a different part? |

| Cynffoneiriau Sut rydych chi'n ychwanegu ymadroddion fel 'Aren’t I', 'Don’t you' a 'Won’t you' i gwestiynau er mwyn swnio fel siaradwr rhugl? | Cynffoneiriau- Tags How do we add phrases such as 'Aren’t I', 'Don’t you' and 'Won’t you' to questions in order to help sound like a native speaker? |

| Er Gall y gair Er olygu naill ai 'although' neu 'despite'. Mae ganddo fe sawl ystyr eraill hefyd - Beth yw'r rhain? | Er- Although / Despite The word Er can mean although or despite, but it also has a few other meanings- what are these? |

| Pen Yn arferol, mae'r gair Pen yn golygu 'head, end, top'. Mae ganddo fe sawl defnydd idiomatig hefyd- Beth yw'r rhain? | Pen: Head, End, Top & Idioms Pen usually means head, end or top, but it also has a few idiomatic uses- what are these? |

| Mynd ati o ddifrif gyda Lluosogion O'r blaen rydyn ni wedi cael cipolwg ar luosogion. Sut mae gwneud lluosogion i fwy o eiriau? | Diving into Plurals Following the earlier glance at plurals, how do we use plurals with a wider range of words? |

| Y Genidol - Defnyddio dau air neu fwy gyda'i gilydd Mae'r Gymraeg yn llai hyblyg na'r Saesneg pan fydd yn cysylltu dau air gyda'i gilydd- sut mae gwneud hyn? | The Genitive- Using two or more nouns together Welsh is less flexible when joining two nouns than English- how do we accomplish this? |

| Y Treiglad Meddal gyda geiriau benywaidd unigol Gawn ni weld rhai esiamplau o'r treigladd meddal gyda geiriau benywaidd unigol? | Soft Mutations with feminine singular nouns Can we have some examples of soft mutations with feminine singular nouns? |

| Atgrynhoi Adferfau Beth yw adferfau, a sut mae eu defnyddio? | Recapping Adverbs What are adverbs and how do we use them? |

| Byth & Erioed Pryd rydyn ni'n defnyddio Byth, a phryd rydyn ni'n defnyddio Erioed? | Byth & Erioed- Ever & Never When do we use Byth and when do we use Erioed? |

| Ta Beth, Bron a Bron i Fi Sut mae defnyddio'r ymadroddion defnyddiol hyn? | Ta Beth, Bron a Bron i Fi- Anyway, Almost, and I Almost How do we use these handy little phrases? |

| Dyma fi’n, Cyfuno Lliwiau & Iawn Sut mae defnyddio Dyma Fi? Sut mae disgrifio arlliwiau? Sut mae defnyddio'r gair Iawn? | Dyma fi’n, Cyfuno Lliwiau & Iawn- A short way of saying 'I am', Combining Colours, and using Iawn How do we use Dyma Fi, how do we describe shades of colours and how can Iawn be used? |

Lefel Canolradd / Intermediate Level

| Allan / Mas, Ar Gyfer, Cam, Er Mywn, Yn Enedigol & Llys Casgliad o gyngor ar y geiriau hyn | Allan / Mas, Ar Gyfer, Cam, Er Mywn, Yn Enedigol & Llys A collection of advice on these words |

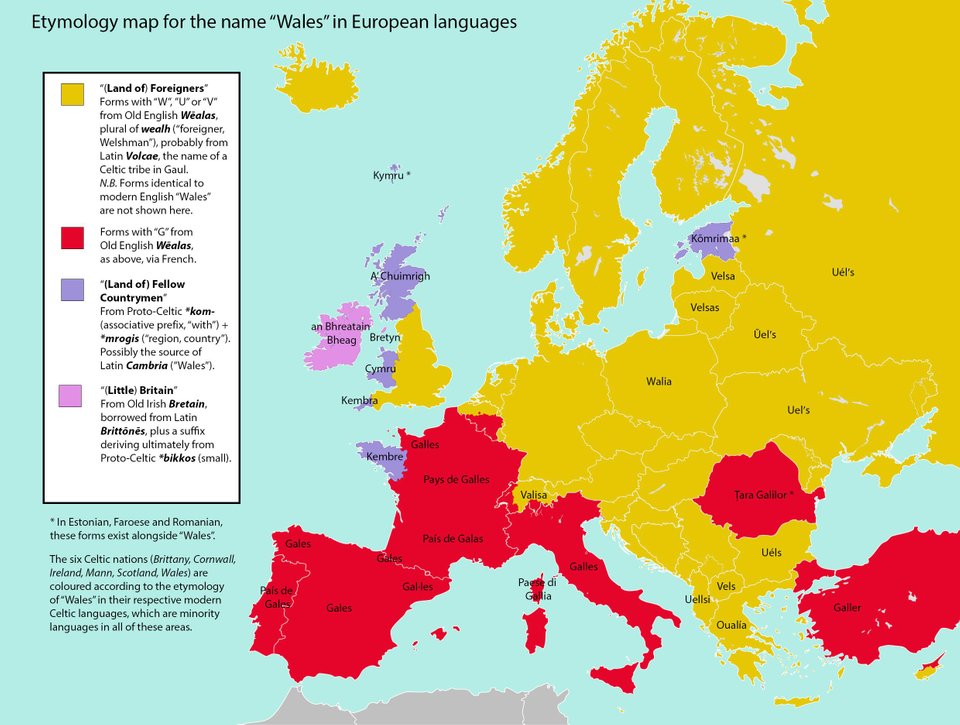

| Cyflwyno enwau gwledydd Oes ffyrdd hawdd o ddysgu llawer o enwau gwledydd? | Introducing country names Are there straightforward ways to learn lots of country names? |

| Yr arddodiad 'i' Mae sawl ffordd o ddefnyddio'r arddodiad 'i'- beth yw'r rhain? | The preposition 'i' 'I' is used as a preposition in many ways- what are these? |

| Defnyddio Mo fel gair negyddol Sut mae defnyddio'r gair negyddol Mo? | Using 'Mo' as a negative How is Mo used to indicate a negative? |

| Ffurfiau amhersonol y berfau afreolaidd Sut ydyn ni’n dod i gyfarwydd â ffurfiau llenyddiol Mynd, Cael, Gwneud, a Dod? | Impersonal forms of the irregular verbs How do we become familiar with formal written forms of Mynd, Cael, Gwneud and Dod? |

| Mwy am Luosogion Gawn ni gael cip arall ar fwy o luosogion? | Extending Plurals Can we take a look at more forms of plurals? |

| Defnyddio Bod yn yr amser presennol a'r amser amherffaith Sut mae defnyddio ymadroddion fel 'Fy mod i' a 'Credir y bydd' mewn cymylau enwol? | Using Bod as That in the present and imperfect tenses How do we use forms such as 'Fy mod i' and 'Credir y bydd'? |

| Ardoddiadau yn Gymraeg ffurfiol Beth yw ystyr ffurfiau llenyddol ar arddodiadau fel 'ataf', 'atom' neu 'atynt'? | Prepositions in formal Welsh When we see prepositions in the form of 'ataf', 'atom' or 'atynt', what do they mean? |

| Gwahaniaethau pwysig rhwng Cymraeg y De a Chymraeg y Gogledd Sut mae patrymau Cymraeg y De yn wahanol i'r rheini yng Nghymraeg y Gogledd? | Key differences between North and South Welsh What are some of the main changes in patterns between North and South Welsh? |

| Atgrynhoi Yn Gadewch i ni edrych ar y gair Yn unwaith eto- beth fydd yn treiglo ar ei hôl hi, a beth na fydd? | Recapping Yn Can we just run through 'Yn' again- what mutates after it and what doesn't? |

| Dadansoddi'r gramadeg yn y gân 'Calon Lân' Rwy'n hoff iawn o'r gân Cymraeg o'r enw Calon Lân, ond mae'n cynnwys Cymraeg llenyddiol- gewch chi esbonio ystyr y geiriau hardd? | Analysing the grammar in 'Calon Lân' I'm really fond of the Welsh song Calon Lân, but it uses formal Welsh- can you talk us through the meaning of the beautiful words? |

| Defnyddio Gwneud yn amser dyfodol Oes ffordd gyflym a hawdd o ddefnydio berfau yn yr amser dyfodol? | Using Gwneud in the future Can you show us a quick and easy way to put verbs into the future tense? |

| Cyflwyno iaith ffurfiol Mae rhai gwahaniaethau rhwng Cymraeg ffurfiol a Chymraeg ar lafar. Beth yw'r pethau mwyaf pwysig i'w deall pan fyddwch chi'n ysgrifennu? | Introducing formal language As formal written Welsh is a little different from spoken Welsh, what are the main things we should learn about it first? |

| Defnyddio'r Amodol Cryno Sut mae defnyddio'r Amodol Cryno i ddweud 'I would go' fel 'Elwn i'? | Using the shortened form of the conditional tense How do we compress phrases such as 'Byddwn i’n mynd' into 'Elwn i'? |

| Yr Amodol: Cymharu'r ffurfiau ar lafar â'r rhai ffurfiol ysgrifenedig Sut y byddwch chi'n ynganu ffurfiau'r Amodol pan fyddwch chi'n gweld geiriau fel 'Licwn i'? | Comparing the written and spoken forms of the Future Conditional tense How do we learn the differences between forms such as 'Licwn i' and 'Licen i' (I would like)? |

| Atgrynhoi ac ymestyn syniadau ynglŷn â Phwyslais Sut mae cyferbynu pethau? Sut mae mynegi syndod neu anghrediniaeth? Sut mae anghytuno? | Recapping and extending the Emphatic form How do we contrast things, express surprise, disbelief, or disagreement? |

| Defnyddio'r geiriau pwysleisiol Taw & Mai, a'r Cyplad yn yr amser presennol, sef Yw Sut mae defnyddio'r geiriau Yw, Taw a Mai i bysleisio rhywbeth? | Using the emphatic words Taw & Mai, and the present-tense connecting form of To Be, that is Yw How do we use Yw, Taw and Mai to emphasise something? |

| Dydd & Diwrnod Y geiriau Dydd a Diwrnod fel ei gilydd sy'n golygu Day, ond byddan nhw'n cael eu defnyddio mewn cyd-destunau gwahanol- beth yw'r rhain? | Dydd & Diwrnod- Words for Day Both 'Dydd' and 'Diwrnod' mean 'Day', but are used in different contexts- what are those? |

| Hwn, Hon, Hwnna, Honno, Y Rhain, Y Rheina & Rheiny Mae'r geiriau hyn i gyd yn eitha tebyg i'w gilydd- beth yw'r gwahaniaeth rhyngddyn nhw? | Demonstrative Adjectives and Pronouns- Saying This, That, These, Those As each of these words is quite similar, how do we tell the difference between them? |

| Fan Hyn & Fanna Sut mae dweud 'By here' ac 'Over there'? | Fan Hyn & Fanna- By here & Over there How do we say things like 'By here' and 'Over there'? |

| Adolygu Ateb Cwestiynau Gawn ni edrych ar y ffyrdd gwahanol o ateb cwestiynau unwaith eto? | Revising Answers to Questions Can we go through again the different ways of answering questions? |

| Cyflwyno Amser Gorffennol Crwyno Bod- Bues, Buest, Buodd, Buon, Buoch & Buont Sut mae dweud pethau fel 'Fuoch chi ar wyliau eleni?' | Introducing the Short Past Tense of Bod- Bues, Buest, Buodd, Buon, Buoch & Buont How do we say things such as 'Did you go on holidays this year?' |

| Yn & Rhwng Mae Yn yn golygu 'in' ac ystyr Rhwng yw 'between'. Rwybryd mae'n anodd pa un y dylech chi ei ddefnyddio- gawn ni egluro hyn? | Yn & Rhwng- In & Between Yn means in and Rhwng means between but it can be unclear when to use which- can we clarify this? |

| Blwydd, Blwyddyn & Blynedd Mae'r geiriau hyn i gyd yn golygu Year, ond maen nhw'n cael eu defnyddio mewn cyd-destunau gwahanol. Pryd y dylen ni ddefnyddio Blwydd, Blwyddyn neu Flynedd? | Blwydd, Blwyddyn & Blynedd- Different words for Year Each of these means 'Year', but is used in different contexts- when do we use which? |

| Arall, Eraill, Y Llall & Y Lleill Mae sawl gair sy'n golygu Other. Sut mae defnyddio'r geiriau gwahanol hyn? | Arall, Eraill, Y Llall & Y Lleill- Words for Other How do we use the different forms of 'Other'? |

| Geiriau Bychain: Y Fannod (Y, Yr, 'R), A & Ac, Â & Ag Beth yw'r ffurfiau gwahanol ar y geiriau Yr, A, ac Â? | Little Words: The Definite Article ('The'), 'And' & 'With' Can we just run through again the differences between these forms of the definite article, and & with? |

| Di Di- yw rhagddodiad sy'n golygu 'heb'. Rydyn ni'n ei weld yn eitha aml- sut mae ei ddefnyddio? | Di- Without or Less I've seen Di, meaning without or less, appear quite often- how can it be used? |

Warning: Parameter 2 to qtranxf_postsFilter() expected to be a reference, value given in /home/parallel/public_html/wp-includes/class-wp-hook.php on line 324

Warning: Parameter 2 to qtranxf_postsFilter() expected to be a reference, value given in /home/parallel/public_html/wp-includes/class-wp-hook.php on line 324

Warning: Parameter 2 to qtranxf_postsFilter() expected to be a reference, value given in /home/parallel/public_html/wp-includes/class-wp-hook.php on line 324

Warning: Parameter 2 to qtranxf_postsFilter() expected to be a reference, value given in /home/parallel/public_html/wp-includes/class-wp-hook.php on line 324

Croeso i ‘Cyflwyno Beirdd Cymru’. Yn yr adnodd hwn byddwch yn dod o hyd i wybodaeth am feirdd sy’n ysgrifennu yn y Gymraeg, neu sydd wedi ysgrifennu am y wlad. Dylanwadwyd ar y beirdd yn y cyflwyniad hwn gan bob agwedd ar Gymru, yn cynnwys traddodiadau barddol Cymraeg, a hanes, tirwedd a diwylliant Cymru. Yma byddwn yn dathlu lleisiau Cymreig, yn cynnwys rhai cyfarwydd, a rhai sy’n llai adnabyddus. Efallai y byddwch yn synnu nad yw rhai enwau cyfarwydd wedi’u cynnwys yn yr adnodd hwn. Roeddwn yn credu ei fod yn bwysig i ddangos yr amrywiaeth sy’n bodoli ym myd barddoniaeth Gymraeg, yn cynnwys y gwahanol arddulliau, o’r traddodiadol i’r arbrofol, sydd wedi bodoli trwy hanes Cymru.

Dyma adnodd addysgol rhad ac am ddim, ar gyfer y rhai sydd â diddordeb yn y Gymraeg, ac yn hanes a barddoniaeth Cymru. Mae wedi’i ysgrifennu er mwyn helpu pobl i ddysgu am feirdd Cymru yn y ffordd hawsaf posib, ac felly mae’n cynnwys dolenni i lyfrau ac erthyglau. Ynglŷn â’r wybodaeth am bob bardd, mae’r lluniau wedi’u cysylltu â gwefannau, ble fyddwch chi’n gallu dod o hyd i rai o’r llyfrau y mae sôn amdanyn nhw yn y cyflwyniad hwn. Mae’r awdur wedi manteisio ar wybodaeth academyddion, haneswyr a beirdd Cymreig blaenllaw wrth greu’r dudalen hon. Ymunwch â ni i ymchwilio i feirdd Cymru drwy hanes y wlad ac i ddarganfod pam mai un enw ar Gymru yw Gwlad frwd y beirdd.

Welcome to 'Introducing Welsh Poets'. In this resource you can expect to find information about poets who wrote in, or about, Wales. The poets in this introduction have been influenced by all aspects of Wales, including Welsh poetic traditions, Welsh history, landscape and culture. It is time to celebrate Welsh voices from the familiar to the new. It might be surprising that certain household names have not been included in this resource. This is because I thought it was important to explore the diversity within Welsh poetry and the range of styles, from the traditional to the experimental, that is present throughout Welsh history.

This is a free educational resource for those interested in Welsh language, history and poetry. It has been written with the intention of making further study of Welsh poets as straightforward as possible, including links to books and articles. The photos that accompany each poet are linked to websites where some of the books mentioned in this introduction can be found. This page has benefited from the knowledge of prominent Welsh academics, historians and poets. Join us in an exploration of Welsh poets throughout Welsh history and discover why Wales is called Gwlad frwd y beirdd.

Wedi'i gasglu a'i olygu gan / Collated and edited by: Rhea Seren Phillips rhea_seren

Gyda chyfraniadau oddi wrth / With contributions from: Aneirin Karadog, Professor Ann Parry Owen, Eurig Salisbury, Natalie Ann Holborow & Norena Shopland.

Mae'r eitem hon ar gael i'w lawrlwytho: / This item is available to download:

Rhestr Cynnwys / Table of Contents

Taliesin / Gwalchmai ap Meilyr / Cynddelw Brydydd Mawr / Iolo Goch / Gwerful Mechain / Guto'r Glyn / Katherine Philips / Huw Morys / Sarah Jane Rees / John Ceiriog Hughes / T.H. Parry-Williams / Lynette Roberts / Mererid Hopwood / Twm Morys / Natalie Ann Holborow / Sophie McKeand

Taliesin (c.534 AD - c.599 AD)

Dros y canrifoedd, mae’r enw Taliesin wedi’i ramantu, ac mae’r bardd wedi cael ei ddyrchafu i fod yn rhan o fytholeg Cymru. Efallai mai un o straeon mwyaf adnabyddus Cymru yw’r chwedl am sut y daeth Taliesin i fod. Roedd y wrach, Ceridwen, wedi gorchymyn i was ifanc droi diod hud am flwyddyn a diwrnod. Bwriadwyd y ddiod ar gyfer ei mab oedd yn wrthun a diddawn pan gafodd ei eni. Penderfynodd Ceridwen fragu diod i newid ei natur. Â’r ddiod yn barod, tasgodd diferyn ar law'r gwas. Ar unwaith, rhoddodd y bachgen ei law yn ei geg i leddfu’r llosg gan yfed y ddiod a derbyn ei buddion i gyd. Ac felly daeth chwedl Taliesin i fod.

Bardd llys cynnar oedd Taliesin. Un o’r Cynfeirdd oedd e, oedd yn weithredol rhwng y 6ed a’r 12fed ganrif, fwy neu lai. Cyfoethog ac amrywiol oedd rôl y bardd yn yr Oesoedd Canol, yn cynnwys bod yn rhyfelwr, diddanwr, proffwyd, a chroniclydd. Roedd barddoniaeth yn draddodiad llafar, ac ysgrifennwyd fel arfer mewn ffurfiau a mesurau barddol, Cymraeg, sef cerdd dafod a chynghanedd. Un o ddyletswyddau bardd llys oedd ysgrifennu barddoniaeth i ganu clodydd noddwr enwog, fyddai’n aml o dras frenhinol (am fwy o wybodaeth am feirdd Cymraeg yn yr Oesoedd Canol, gweler y cyswllt isod). Roedd Taliesin yn enwog am ei allu i wneud hyn. Ymhlith rhai eraill, ysgrifennodd ddeuddeg o gerddi mawl i’w noddwr, y Brenin Urien Rhedeg a’i fab, Owain.

- Aneirin oedd un o gydoeswyr Taliesin.

- ‘Talcen disglair’ yw ystyr yr enw Taliesin.

- Ysgrifennwyd Hanes Taliesin yn y 16eg ganrif gan Elis Gruffydd.

The name Taliesin has been romanticised throughout the centuries and the poet has transcended into myth. The story of how Taliesin came to exist is perhaps one of Wales’ most well-known stories. The witch Ceridwen tasked a serving boy to stir a potion for a year and a day. The potion was intended for her son who had been born grotesque and talentless. Ceridwen decided to brew a potion to alter his nature. Just as the potion was ready, a splash fell on the serving boy's hand. The boy immediately brought his hand to his mouth to ease the burn, consuming the potion and all of its benefits. And so, the legend of Taliesin was born.

Taliesin was an early Welsh court poet. He was one of the Y Cynfeirdd or 'The Early Poets' who were active around the 6th to 12th century. The role of the medieval poet was a rich and varied one that included warrior, entertainer, prophet and chronicler. Poetry was an oral tradition that was usually written in Welsh poetic forms and metre or cerdd dafod and cynghanedd. One of the duties of a court poet was to write panegyric verse or poetry written in praise of a celebrated patron, these individuals were often of royal descent (for more information about medieval Welsh poets see the link below). Taliesin was renowned for this ability. Among others, he wrote twelve praise poems for his patron, King Urien Rheged and his son, Owain.

- Aneirin was one of Taliesin's contemporaries.

- The name Taliesin means 'radiant brow' or 'shining brow'.

- Hanes Taliesin was written in the 16th century by Elis Gruffydd.

Darn oddi wrth 'Marwnad Owain ab Urien'

Cysgid Lloegr llydan nifer

A lleufer yn eu llygaid.

Extract from 'Marwnad Owain ab Urien'

Wide England’s host would sleep

With the light in their eyes.

Books

Taliesin. 1988. Taliesin Poems. Translated from Welsh to English by Meirion Pennar. Wales. Llanerch Press. (See above photo.)

Lewis, G. Williams, R. 2019. The Book of Taliesin: Poems of Warfare and Praise in an Enchanted Britain. England. Penguin Classics.

Links

BBC Wales. Early Welsh Literature: Taliesin.

BBC Wales. The Life of Taliesin the Bard.

Phillips, R.S. The Conversation. 2017. How the Welsh developed their own form of poetry.

Roedd Gwalchmai ap Meilyr yn un o’r cynharaf o Feirdd y Tywysogion neu’r Gogynfeirdd. Hanai o deulu o feirdd proffesiynol o Fôn (ac fe’i cysylltir yn arbennig â Threwalchmai). Bu ei dad, Meilyr Brydydd, yn fardd llys i’r Tywysog Gruffudd ap Cynan (marw 1137). Mae’r cerddi sydd wedi goroesi yn awgrymu cyswllt arbennig rhyngddo a’r Tywysog Owain Gwynedd (marw 1170), mab Gruffudd ap Cynan, yn ogystal â brodyr a meibion Owain. Roedd Madog ap Maredudd, tywysog Powys, yntau’n noddwr pwysig iddo, a chyfansoddodd awdl farwnad hir yn dilyn marwolaeth Madog yn 1160. Yn ogystal â’r cerddi mawl a marwnad traddodiadol, cadwyd ganddo gerddi crefyddol a myfyrgar, a hefyd gerdd Orhoffedd, lle mae’n ymffrostio yn ei alluoedd milwrol ef ei hun a rhai ei noddwr, Owain Gwynedd, ac yn llawenhau yn agweddau ar serch a natur. Cadwyd barddoniaeth Gwalchmai mewn dwy lawysgrif bwysig o’r Oesoedd Canol, sef Llawysgrif Hendregadredd (c.1300) a Llyfr Coch Hergest (c.1400). Gwelir yn llinellau agoriadol ei Orhoffedd y llawenydd personol a’r brwdfrydedd sy’n nodweddu llawer o’i waith.

Gwalchmai ap Meilyr was one of the earliest of the Poets of the Princes or Gogynfeirdd. He belonged to a family of professional poets from Anglesey (and is associated in particular with Trewalchmai). His father, Meilyr Brydydd, was the court poet of Prince Gruffudd ap Cynan (died 1137). Gwalchmai’s extant poetry suggests a particularly close relationship with Prince Owain Gwynedd (died 1170), Gruffudd ap Cynan’s son, and Owain’s brothers and sons. Madog ap Maredudd, prince of Powys, to whom he composed a long elegy following his death in 1160, was also an important patron. As well as the traditional eulogies and elegies, Gwalchmai’s repertoire contains religious poems, poems of reflection, and his Gorhoffedd, a ‘boasting’ poem celebrating his own military exploits as well as those of his patron, Owain Gwynedd, and rejoicing in aspects of love and nature. Gwalchmai’s poetry has survived in two major medieval manuscripts, The Hendregadredd Manuscript (c.1300) and the Red Book of Hergest (c.1400). The opening lines of his Gorhoffedd convey the personal joy and enthusiasm that characterize much of his poetry.

Mochddwyreawg huan haf dyffestin,

Maws llafar adar, mygr hear hin.

Mi ydwyf eurddeddf ddiofn yn nhrin,

Mi ydwyf llew rhag llu, lluch fy ngorddin.

Early to rise is the sun in summer which is quickly approaching,

Sweet is the birdsong, splendid and fine is the weather.

I am a man of magnificent and fearless attributes in battle,

I am a lion at the front of a regiment, my onslaught is a lightning flash.

Books

For Gwalchmai ap Meilyr’s poetry, see J. E. Caerwyn Williams and Peredur I. Lynch, Gwaith Meilyr Brydydd a’i Ddisgynyddion (Cardiff, 1994), pp. 127–313.

Am waith Gwalchmai ap Meilyr, gweler J. E. Caerwyn Williams a Peredur I. Lynch, Gwaith Meilyr Brydydd a’i Ddisgynyddion (Caerdydd, 1994), tt. 127–313.

Links

Lloyd, D.M. 1959. Gwalchmai ap Meilyr (fl.1130 - 1180), an Anglesey Court Poet.

Roedd Cynddelw Brydydd Mawr yn un o Feirdd y Tywysogion neu Ogynfeirdd y ddeuddegfed ganrif. Canodd fawl i dywysogion pwysicaf ei oes: Madog ap Maredudd o Bowys (marw 1170), Owain Gwynedd (marw 1170), Owain Cyfeiliog (marw 1197) a’r Arglwydd Rhys ap Gruffudd o Ddeheubarth (marw 1197). Ef yw’r mwyaf toreithiog o’r beirdd llys, a chadwyd 3,847 llinell o’i farddoniaeth (mewn 48 cerdd) yn rhai o brif lawysgrifau Cymraeg yr Oesoedd Canol, yn cynnwys Llyfr Du Caerfyrddin (c.1250), Llawysgrif Hendregadredd (c.1300) a Llyfr Coch Hergest (c.1400). Mae ei repertoire yn eang, ac yn ogystal â cherddi traddodiadol o fawl a marwnad, canodd awdl hir yn moli eglwys Meifod a’i nawddsant Tysilio, cerddi crefyddol, cerddi dadolwch (cymod), cerddi diolch a cherddi serch. Roedd Cynddelw yn bencerdd, a nodweddir ei farddoniaeth gan hunanhyder ac ymwybyddiaeth o’i statws uchel. Mewn awdl yn cyfarch yr Arglwydd Rhys o’r Deheubarth, un o’r dynion mwyaf pwerus yn ei ddydd, mae’n atgoffa Rhys o’r ffaith eu bod yn llwyr ddibynnol ar ei gilydd, y naill heb lais ac felly’n ddi-rym heb y llall.

Cynddelw Brydydd Mawr was one of the twelfth-century Poets of the Princes or Gogynfeirdd. He sang the praises of the most important princes of his age: Madog ap Maredudd of Powys (died 1170), Owain Gwynedd (died 1170), Owain Cyfeiliog (died 1197) and Lord Rhys ap Gruffudd of Deheubarth (died 1197). He is the most prolific of all the court poets, 3,847 lines of poetry (in 48 poems) having survived in some major medieval Welsh manuscripts, including The Black Book of Carmarthen (c.1250), The Hendregadredd Manuscript (c.1300) and The Red Book of Hergest (c.1400). His repertoire was vast, and as well as the traditional eulogies and elegies, he composed a long poem for the church of Meifod and its patron saint, Tysilio, religious poems, poems of appeasement, poems of thanks and two love poems. Cynddelw was a master craftsman, and his poetry is characterized by a certain self-confidence and awareness of his high status as he addresses his patron princes. In an awdl for the great Lord Rhys of Deheubarth, he reminds Rhys of their interdependency, neither having a voice, and therefore powerless, without the other (an extract from the poem can be read below).

Ti hebof, nid hebu oedd tau,

Mi hebod, ni hebaf finnau.

You without me, you would have no voice,

Me without you, I have no voice either.

Books

Parry Owen, A. Jones, N. 1992. Gwaith Cynddelw Brydydd Mawr V.1. Wales. University of Wales Press. (See above photo).

Links

Myrddin Lloyd, D. Dictionary of Welsh Biography. 1959. Cynddelw Brydydd Mawr (fl. 1155-1200), the leading 12th century Welsh court poet.

Professor Ann Parry Owen is a Research Project Leader at The University of Wales Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies and Senior Editor at the Dictionary of the Welsh Language. Her principle field of research is medieval Welsh language and poetry. She is particularly interested in the poetry, metrics and language of the Poets of the Princes, the later Gogynfeirdd who sang in the fourteenth century, and in the later poetical tradition of the fifteenth century. She is the co-editor (with Nerys Ann Jones) of two volumes, Gwaith Cynddelw Brydydd Mawr I and II, in the ‘Poets of the Princes Series’, and she has editions of later texts in the 'Poets of the Nobility Series' of which she is the series editor. Professor Ann Parry Owen was the Principal Investigator on the AHRC five-year team-based Guto’r Glyn Project (2008–13) and general editor of the new electronic edition that is freely available online at www.gutorglyn.net.

Iolo Goch (c.1320 - c.1398)

Roedd Iolo Goch yn fardd llys yn yr Oesoedd Canol a gafodd ei eni yn Nyffryn Clwyd. Roedd yn ysgrifennu gan ddefnyddio’r traddodiad barddol Cymraeg o gerdd dafod a chynghanedd, ac yn ffafrio’r cywydd. Roedd Iolo’n ysgrifennu yn arddull y Gogynfeirdd, gan ddefnyddio iaith sy’n atgoffa dyn o Gymru hŷn. Ithel ap Robert, archddiacon Llanelwy, teulu’r Tuduriaid o Fôn, ac Owain Glyndŵr oedd ei noddwyr, a chyrhaeddodd un o’i gerddi ddwylo’r Brenin Edward III Lloegr, hyd yn oed (1347). Dangosodd y gerdd wybodaeth am frwydrau yn Lloegr, Iwerddon, a Ffrainc. Mae’i weithiau eraill yn cynnwys cerddi disgrifiadol, ac roedd un ohonyn nhw’n sôn am neuadd fawr Sycharth, oedd yn gartref i Owain Glyndŵr, yn ogystal â cherddi oedd yn ceisio ategu trefn ddwyfol, wleidyddol, a chymdeithasol (Mae’r ‘Y Llafurwr’ yn enghraifft o hyn). Roedd yn gydoeswr i Dafydd ap Gwilym a Llywelyn Goch Amheurig Hen.

Iolo Goch was a medieval court poet who was born in the Vale of Clwyd (his name translates to Iolo the Red). He wrote using the Welsh poetic tradition of cerdd dafod and cynghanedd, favouring the cywydd form. Iolo wrote in the style of the Y Gogynfeirdd, his use of language reminiscent of an older Wales. His patrons were Ithel ap Robert, an archdeacon of St. Asaph, the Tudur family of Anglesey, Owain Glyndŵr and one of his poems even reached the hands of King Edward III of England (1347). The poem displayed a knowledge of battles in England, Ireland and France. His other works include descriptive poems, one of which was about the great hall of Sycharth, home to Owain Glyndŵr, as well as poems that sought to uphold divine, political and social order ('The Labourer’ is an example of this). He was a contemporary of Dafydd ap Gwilym and Llywelyn Goch Amheurig Hen.

Llys barwn, lle syberwyd,

lle daw beirdd aml, lle da byd;

Gwawr Bowys fawr, beues Faig,

Gofuned gwiw ofynaig.

Baron's palace, place of generosity,

Where the bards come often, a good place;

Lady of great Powys, land of Maig,

A place of great promise.

Books

Goch, I. 2010. Welsh Classic Series: Iolo Goch Poems. Wales. Gomer Press. (See above photo.)

Links

Lewis, Prof.H. Dictionary of Welsh Biography. 1959. Iolo Goch (c.1320-c.1398), poet.

Canolfan Owain Glyndŵr Centre. Llys Owain Glyndŵr (the court of Owain) - a poem by Iolo Goch.

Roedd Gwerful Mechain yn ferch i Hywel Fychan o Fechain ym Mhowys. Roedd ei thad yn aelod o’r teulu Vaughan, ac roedd Gwerful yn meddu ar y breintiau a ddaw o gael ei geni i deulu â statws uchel a boheddig. Roedd hi’n fardd canoloesol y mae cryn dipyn o’i gwaith wedi goroesi. Roedd hi hefyd yn fardd arloesol, ac mae hyn i’w weld yn y pynciau ddewisodd hi. Roedd hi’n un o’r beirdd cyntaf i ysgrifennu am gamdriniaeth deuluol; Mae ‘I’w Gŵr am ei Churo’ yn gerdd deimladwy, gref yn llawn o iaith ddig a delweddaeth llawn egni. Roedd hi’n fardd cynhyrchiol nad oedd wedi’i chyfyngu i un arddull, ond mae’i gwaith yn cynnwys barddoniaeth grefyddol a doniol, a cherddi’n dangos ymwybyddiaeth gymdeithasol. ‘Cywydd y Cedor’ yw un o’i gweithiau enwocaf. Dyma gerdd sy’n ceryddu’i chymheiriaid gwryw am ganu clodydd corff menyw o’r corun i’r sawdl tra byddan nhw’n anwybyddu un nodwedd gêl. Cafodd y gerdd ei hysgrifennu mewn ymateb i 'Cywydd y Gal' gan Dafydd ap Gwilym.

Roedd Gwerful yn sylwedydd craff ar gymdeithas ganoloesol. Ysgrifennwyd ei cherddi crefyddol, sy’n cydymffurfio â moesoldeb caethiwus cymdeithas ganoloesol, yn gaeth, mewn cynghanedd, ond mae rhai o’i cherddi eraill yn fwy rhydd o ran y mesur, yn dangos ei meistrolaeth ar y grefft. Roedd Gwerful yn gydoeswr i Dafydd Llwyd a Llywelyn ap Gutyn, a byddai’n gohebu â nhw’n rheolaidd.

Gwerful Mechain was the daughter of Hywel Fychan from Mechain, Powys. Her father belonged to the Vaughan family, and Gwerful enjoyed the privileges that being born into a high-status and noble family afforded her. She was a medieval poet with a substantial surviving body of work. She was also an innovative poet which is reflected in her choice of subject matter. She one of the first poets to write about domestic abuse; ‘To Her Husband for Beating Her’ is a poignant and powerful poem full of enraged language and energetic imagery. She was a prolific poet who was not restricted to one style, her work includes religious, humorous and socially conscious poetry. One of her most well-known works is ‘Ode to a Vagina’, a poem that chastises her male counterparts for praising a woman’s body from her hair to her feet but ignoring one hidden feature. The poem was written in response to Dafydd ap Gwilym's 'Ode to a Penis' or 'Cywydd y Gal'.

Gwerful was a keen observer of medieval society. Her religious poems, which conform to the restrictive morality of medieval society, were written in strict cynghanedd, while some of her other poems had a relaxed attitude towards the metre, displaying her mastery of the craft. Gwerful was a contemporary of Dafydd Llwyd and Llywelyn ap Gutyn, who she corresponded with on a regular basis.

Darn oddi wrth 'A Response to Ieuan Dyfi's poem on Red Annie'

Gwae'r undyn heb gywreinddu,

Gwae'r un wen a garo neb;

Ni cheir gan hon ei charu,

Yn dda, er ei bod yn ddu.

Extract from 'A Response to Ieuan Dyfi's poem on Red Annie'

Woe betide you, incompetent bard,

Who sings the praise of the chaste blonde,

While the loving, clever dark one

Gets lambasted and shunned.

Books

Gramich, K. 2018. The Works of Gwerful Mechain. Canada. Broadview Press. (See above photo.)

Links

Rattle. 2017. Gwerful Mechain: 'To Her Husband for Beating Her'.

Harries, L. 1959. Dictionary of Welsh Biography. Gwerful Mechain (1462? - 1500), poetess.

Swansea University. The Welsh Department. Dafydd ap Gwilym.

Eurig Salisbury a Barry J. Lewis: "Er mor anghyflawn yw’r darlun ar adegau, eto fe gawn [yn ei waith] gipolwg cyffrous ar Guto mewn lleoliadau arbennig ar adegau arbennig, ac yn raddol fe ddaw i’r amlwg amlinelliad o yrfa bardd ac iddi arwyddocâd gwir genedlaethol a rhyngwladol."

Cyfansoddai Guto yn Gymraeg. Cafodd ei eni yn nyffryn Ceiriog a bu’n byw am gyfnod yng Nghroesoswallt, lle cafodd fod yn fwrdais yn gyfnewid am ganu cerdd o fawl i’r dref. Teithiodd Gymru a’r gororau benbaladr, ac fe’i claddwyd yn abaty Glyn-y-groes.

- Bardd mwyaf y bymthegfed ganrif.

- Cymerodd ran fel milwr yn y Rhyfel Can Mlynedd a bu’n dyst i brif ddigwyddiadau Rhyfeloedd y Rhosynnau yng Nghymru.

- Canodd fawl i uchelwyr mwyaf blaenllaw ei ddydd ar hyd a lled Cymru, yn fwyaf nodedig i Syr Wiliam Herbert o Raglan yn ystod ei fuddugoliaethau a’i gwymp yn yr 1460au.

- Roedd yn bennaf gysylltiedig ag abaty Ystrad Fflur, Rhaglan, Croesoswallt (lle bu’n byw fel bwrdais) ac abaty Glyn-y-groes, lle bu farw a lle’i claddwyd.

Gruffudd Aled Williams– "According to the later poet Tudur Aled it was Guto of all Welsh poets who excelled in composing praise poems to noblemen: his work amply bears out this judgement, often boldly transcending poetic convention and delighting with its wit, vigour, and original imagery."

Guto composed in Welsh. He was born in the Ceiriog valley and lived for a time in Oswestry, where he was made a burgess in exchange for composing a poem of praise for the town. He travelled all over Wales and the marches. He was buried in the abbey of Valle Crucis.

- The greatest poet of the fifteenth century.

- Took part as a soldier in the Hundred Years War and witnessed the most important events of the Wars of the Roses in Wales.

- Composed praise poetry for the leading noblemen of his day in every part of Wales, most notably for Sir William Herbert of Raglan during his spectacular rise and fall in the 1460s.

- Principally associated with Strata Florida abbey, Raglan, Oswestry (where he lived as a burgess) and Valle Crucis abbey.

'Moliant i Wiliam Herbert o Raglan, iarll cyntaf Penfro, ar ôl cipio castell Herlech, 1468'

Na fwrw dreth yn y fro draw

Ni aller ei chynullaw.

Na friw Wynedd yn franar,

N’ad i Fôn fyned i fâr,

N’ad y gweiniaid i gwynaw

Na brad na lledrad rhag llaw.

N’ad trwy Wynedd blant Rhonwen

Na phlant Hors yn y Fflint hen.

Na ad, f’arglwydd, swydd i Sais,

Na’i bardwn i un bwrdais.

Barna’n iawn, brenin ein iaith,

Bwrw ’n y tân eu braint unwaith.

Cymer wŷr Cymru’r awron,

Cwnstabl o Farstabl i Fôn.

Dwg Forgannwg a Gwynedd,

Gwna’n un o Gonwy i Nedd.

O digia Lloegr a’i dugiaid,

Cymru a dry yn dy raid.

gutorglyn.net 21.53–70

'In praise of William Herbert of Raglan, first earl of Pembroke, after the capture of Harlech castle, 1468'

Do not exact a tax on the land over there

Which cannot be gathered.

Do not churn up Gwynedd into fallow-land,

Do not let Anglesey fall into misery,

Do not let the weak lament

Either treachery or theft from now on.

Do not let Rhonwen’s children roam Gwynedd

Nor the children of Horsa into ancient Flint.

Do not, my lord, allow any office to an Englishman,

Nor give any burgess his pardon.

Judge rightly, king of our nation,

Cast their privilege into the fire once and for all.

Take now the men of Wales,

Constable from Barnstaple to Anglesey.

Take Glamorgan and Gwynedd,

Make all one from the Conwy to the Neath.

If England and her dukes are angered,

Wales will come to your need.

gutorglyn.net 21.53–70

Books

Parry Owen, A. 2017. Plu Porffor a Chlog o Fwng Ceiliog: Cynddelw Brydydd Mawr a Guto'r Glyn. Wales. University of Wales for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies.

Williams. I. 1979. Gwaith Guto'r Glyn. Wales. University of Wales Press. (See above photo.)

Links

The University of Wales. Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies. 2011. The Poetry of Guto'r Glyn.

Williams, Sir. I. Dictionary of Welsh Biography. 1959. Guto'r Glyn, a bard who sang during the second half of the 15th century (1440-1493).

Eurig Salisbury is an English and Welsh language poet. He graduated from Aberystwyth University in 2004 and 2006, where he now works as a lecturer. He won the Chair at the Urdd Festival in Denbighshire in 2006. Eurig was the first to hold the prestigious position of Bardd Plant Cymru or Welsh Children's Laureate for two years (2011 - 2013). Eurig Salisbury is the Welsh-language editor for 'Poetry Wales'. eurig | eurig.cymru/blog | soundcloud.com/podlediad_clera

Katherine Philips (c.1632 - c.1664)

Cyflwyniad gan / Introduction by: Norena Shopland

Cafodd Katherine Philips ei geni yn Llundain, ond treuliodd y rhan fwyaf o’i bywyd yng Nghymru. O’i chartref yn Aberteifi ysgrifennodd farddoniaeth a sicrhaodd ei bod yn cael ei chydnabod fel y bardd Prydeinig benyw cyntaf o bwys. Hi oedd y wraig gyntaf hefyd i gael llwyfannu drama’n fasnachol. Roedd hi’n adnabyddus yn ei chyfnod ei hun, ond diflanodd ei gwaith o olwg y byd yn ddiweddarach, a dim ond yn yr 20fed ganrif y sylweddolwyd ei wir werth. Pan ddechreuodd ysgrifenwyr ffeministaidd dynu sylw at ei barddoniaeth cafodd ei harddel fel un o feirdd mwyaf dylanwadol yr iaith Saesneg.

Mae llawer o’r drafodaeth ynghylch barddoniaeth Katherine yn canolbwyntio ar ofyn a oedd hi’n lesbiad ai peidio. Y rheswm am hyn yw bod ei gwaith yn ffocysu’n emosiynol ar fenywod, a’r perthnasoedd nwydwyllt yr oedd hi’n eu cael â nhw. Ni waeth beth fo rhywioldeb Katherine dyma’r cerddi Prydeinig cyntaf sy’n mynegi cariad rhwng dwy fenyw.

Katherine Philips was born in London, but spent most of her life in Wales. From her home in Cardigan she was to write poetry that marked her out as the first significant female British poet, as well as the first woman to have a commercial play staged. Well-known in her own time she fell into obscurity and it was not until the late 20th century that her true worth was realised. When feminist writers began to highlight her poetry she was finally acknowledged as one of the most influential women poets in the English language.

Much discussion around Katherine’s poetry and life concentrates on whether she was or was not a lesbian. For the emotional focus of her poetry was on women and the passionate relationships she had with them. Regardless of Katherine’s own sexual orientation they are the first British poems which express same-sex love between women.

Extract from 'To the Queen of Inconstancy, Regina Collier'

And you kill me, because I worshipp’d you.

But my worst vows shall be your happiness,

And nere to be disturb’d by my distress.

And though it would my sacred flames pollute,

To make my Heart a scorned prostitute;

Yet I’le adore the Authour of my death,

And kiss the hand that robbs me of my breath.

Books

Shopland, N. 2017. Forbidden Lives: LGBT Stories from Wales. Wales. Seren. (See above photo).

Philips, K. 2018. Poems by the Most Deservedly Admired Mrs. Katherine Philips (Classic reprint). England.Forgotten Print.

Thomas, P. Philips, K. 1990. The Collected Works of Katherine Philips: The Matchless Orinda. England. Stump Cross Books.

Orvis, D.L. 2015. Noble Flame of Katherine Philips. U.S.A. Duquesnes University Press.

Links

Jokinen, A. 2003. The Works of Katherine Philips.

Poetry Foundation. Katherine Philips.

British Library. Katherine Philips.

Norena Shopland has a Master’s degree in heritage studies and has worked with leading heritage organisations including National Museums Wales, Glamorgan Archives and Cardiff Story Museum. She has extensively researched the heritage of LGBT people and issues in Wales for 15 years. She devised the first project in Wales to look at placing sexual orientation and gender identity into Welsh history, culminating in the Welsh Pride, the first exhibition exclusively on Welsh LGBT people, allies and events, and managed Gender Fluidity, the first funded transgender project in Wales. Norena arranged for Gillian Clarke to write the first poem in the world by a national or poet laureate celebrating the LGBT people of a country. NorenaShopland

Huw Morys (c.1622 - c.1709)

Cyflwyniad gan / Introduction by: Eurig Salisbury

Canai Huw Morys yn Gymraeg. Bardd mwyaf yr ail ganrif ar bymtheg. Roedd yn byw ar ffermdy Pont-y-meibion ger y Pandy yn nyffryn Ceiriog. Fe’i claddwyd yn eglwys Llansilin, lle roedd yn warden.

- Un o’r beirdd olaf i ennill ei fywoliaeth yn canu cerddi i bobl yn ei gymuned.

- Gwnaeth ddefnydd arloesol o’r gynghanedd ar fesurau rhydd newydd.

- Canodd gerddi i fwy nag un haen yn y gymdeithas, o’r tlawd i’r mwyaf cefnog.

- Thomas Parry: ‘Y mwyaf toreithiog, ac ar lawer ystyr y gloywaf ei ddawn o feirdd [yr ail ganrif ar bymtheg] … un o brif feirdd Cymru.’

Huw Morys composed in Welsh and he is considered to be the greatest poet of the 16th century. He lived at Pont-y-meibion farmhouse near Pandy in the Ceiriog valley. He was buried in Llansilin church, where he served as a warden.

- He was one of the last poets to earn a living composing poetry for his community.

- He made innovative use of ‘cynghanedd’ in new free metres.

- He composed poetry for all levels in society, from the poor to the wealthy.

- Thomas Parry: "the most prolific and in many ways the brightest bardic talent of the seventeenth century – one of the great Welsh poet."

Darn oddi wrth ‘Codi Nant-y-cwm’ (gofyn i grefftwyr adeiladu tŷ i dlodion)

Fi a’m holl gymdeithion,

Os gwir yw gwers y person,

Troed y ffordd i’r nefoedd gu

Yw adeiladu i dlodion.

Extract from ‘To build Nant-y-cwm’ (request for craftsmen to build a house for the poor)

Myself and all my companions,

if the parson’s sermon is true,

the beginning of the road to beloved heaven

is to build for the poor.

Books

Morys, H. Jones, F.M (ed). 2008. Y Rhyfel Cartrefol. Wales. School of Welsh, Bangor University. (See above photo.)

Parry, T. 1962. The Oxford Book of Welsh Verse. England. Oxford University Press.

Eurig Salisbury is an English and Welsh language poet. He graduated from Aberystwyth University in 2004 and 2006, where he now works as a lecturer. He won the Chair at the Urdd Festival in Denbighshire in 2006. Eurig was the first to hold the prestigious position of Bardd Plant Cymru or Welsh Children's Laureate for two years (2011 - 2013). Eurig Salisbury is the Welsh-language editor for 'Poetry Wales'. eurig | eurig.cymru/blog | soundcloud.com/podlediad_clera

Sarah Jane Rees (1839 - 1916)

Cyflwyniad gan / Introduction by: Norena Shopland

Pan fu farw Sarah Jane Rees ym 1916, dywedodd yr ysgrif goffa yn y Carmarthen Journal y canlynol: “Gall dyn honni’n ddiogel nad yw’r un Gymraes arall wedi bod mor boblogaidd mewn cymaint o feysydd cyhoeddus ag oedd Cranogwen.”

Cranogwen oedd yr enw barddol a ddaeth ag enwogrwydd Sarah – mae’n gyfuniad o ddau air: Sant Crannog, yr enwyd Llangrannog ar ei ôl, a Nant Hawen, yr afon leol – ac yn wir llwyddodd hi i wneud nifer fawr o bethau yn ystod ei bywyd. Roedd hi’n forwr, athro, bardd arobryn, ysgrifennwr a golygydd, a phregethwr lleyg. Yn ystod ei hoes, gwnaeth gryn dipyn i hyrwyddo ysgrifenwyr benyw yng Nghymru, ond nad ydym yn gwybod llawer amdani heddiw.

Trwy ei hysgrifennu y daeth Cranogwen yn enwog, dros nos, bron. Yn 1865, cystadlodd yn yr Eisteddfod Genedlaethol, y digwyddiad cymdeithasol hwnnw sy’n Gymraeg i’r gwraidd. Yn y Brifwyl yn Aberystwyth, cyflwynodd gerdd o’r enw ‘Y Fodrwy Briodasol’. Rhaid i bob awdur ddewis ffugenw, ac felly pan ddaeth i’r golwg mai menyw oedd wedi ennill, roedd pawb yn synnu. Roedd hi wedi bod yn cystadlu yn erbyn ysgrifenwyr gwryw enwog a chydnabyddedig.

When Sarah Jane Rees died in 1916 Carmarthen Journal’s obituary said “It can safely be claimed that no other Welsh woman enjoyed popularity in so many public spheres as Cranogwen did."

Cranogwen was the bardic name for which Sarah was to become famous - a combination of Saint Cranog after whom Llangrannog was named and Hawen the local river, and she certainly covered a lot of ground in her life. She was a sailor, teacher, award winning poet, writer and editor and lay preacher. In her time she did an enormous amount for the advancement of Welsh women writers but today is little known.

It was through her writing that Cranogwen became a celebrity almost overnight. In 1865 she entered that quintessentially Welsh cultural event, the Eisteddfod. At the nationals in Aberystwyth she entered a poem ‘Y Fodrwy Briodasol’ ('The Wedding Ring'). All entries are anonymous and so when it was revealed a woman had won there was genuine shock. She had been competing against established and renowned male writers.

Darn oddi wrth 'Fy Ffrynd'

Ah! Annwyl chwaer, ‘r wyt ti i mi,

Fel lloer I’r lli, yn gyson;

Dy ddilyn heb orphwyso wna

Serchiadau pura’m calon.

Extract from 'My Friend'

Oh! My dear sister, you to me

As the moon to the sea, constantly,

Following you restlessly are

My heart’s pure affections.

Books

John, A.V. 2011. Our Mothers' Land: Chapters in Welsh Women's History, 1830-1939. Wales. University of Wales Press.

Jones, D.G. 1981. Cranogwen: Portread Newydd. Wales. Gomer Press. (out of print.)

Links

Matthews, C. BBC Wales. 2019. Hidden Heroines.

Carradice, P. BBC Wales. 2013. Sarah Jane Rees, schoolteacher and poet.

WENWales. Sarah Jane Rees "Cranogwen".

Norena Shopland has a Master’s degree in heritage studies and has worked with leading heritage organisations including National Museums Wales, Glamorgan Archives and Cardiff Story Museum. She has extensively researched the heritage of LGBT people and issues in Wales for 15 years. She devised the first project in Wales to look at placing sexual orientation and gender identity into Welsh history, culminating in the Welsh Pride, the first exhibition exclusively on Welsh LGBT people, allies and events, and managed Gender Fluidity, the first funded transgender project in Wales. Norena arranged for Gillian Clarke to write the first poem in the world by a national or poet laureate celebrating the LGBT people of a country. NorenaShopland

John Ceiriog Hughes (1832 - 1887)

Cafodd John Ceiriog Hughes ei eni ar fferm yn edrych dros bentref Llanarmon Dyffryn Ceiriog yng ngogledd-ddwyrain Cymru. Gadawodd yno i fynd i Fanceinion yn 1849, ble gweithiai fel rheolwr rheilffordd rhwng Manceinion a Llundain. Ychydig wedi hynny, cymerodd swydd fel clerc yn Llundain. Yn ddiweddarach, symudodd i orsaf reilffordd Caersws a gweithiodd yno am weddill ei oes.

Cymerodd ei enw barddol o afon yn llifo’n agos i’w gartre’, Afon Ceiriog. Teitl ei gasgliad cyntaf o farddoniaeth, wedi’i gyhoeddi yn 1860, oedd 'Oriau’r Hwyr' ('Evening Hours'). Dylanwadwyd ar ei waith gan y Gymru wledig, a chan berseinedd barddoniaeth ac alawon gwerin Cymraeg, yn enwedig y rhai a oedd yn deffro atgofion bore oes.

Yn ystod y cyfnod a dreuliodd yn Lloegr, dylanwadwyd ar Ceiriog gan y Cymry John Hughes, R.J. Derfel ac Idris Fychan, oedd yn aelodau o gymdeithas lenyddol. Roedd Idris Fychan yn arfer canu’r delyn, offeryn cerdd traddodiadol oedd yn cael ei ddefnyddio i gyfeilio i farddoniaeth Gymraeg ganoloesol. Roedd R.J. Derfel yn gefnogwr pybyr o hanes, iaith a diwylliant Cymru. Mae’u dylanwad i’w gweld yn y llyfr 'Cant o Ganeuon: Yn Cynwys, Y Gyfres Gyntaf o Eiriau ar Alawon Cymreig', y gyntaf o bedair cyfrol (y cyhoeddwyd dim ond un ohonyn nhw).

- O bryd i’w gilydd, cyfeirir ato fel ‘Robert Burns barddoniaeth Gymraeg’.

- Cafodd ei hudo gan ganeuon gwerin Cymraeg, ac ysgrifennodd gerddi telynegol yn dilyn eu rhythm. Mae’r rhain yn cynnwys 'Dafydd y Garreg Wen'.

John Ceiriog Hughes was born on a farm overlooking the village of Llanarmon Dyffryn Ceiriog in North-East Wales. He left for Manchester in 1849 where he worked as a railway manager between Manchester and London. Shortly after he took a job as a clerk in London. In later life, he moved to Caersws railway station where he worked until his death.

He took his bardic name from a river that ran close to his home, the River Ceiriog. His first collection of poetry, published in 1860, was called 'Evening Hours' or 'Oriau’r Hwyr'. His work was influenced by rural Wales and the musicality of Welsh poetry and folk tunes, particularly those that invoked memories of childhood.

During his time in England, Ceiriog was influenced by Welshmen John Hughes, R.J.Derfel and Idris Fychan who were members of a literary society. Idris Fychan played the harp, a traditional instrument used to accompany medieval Welsh poetry. R.J.Derfel was a staunch promoter of Welsh history, language and culture. Their influence can be seen in 'Cant o Ganeuon: Yn Cynwys, Y Gyfres Gyntaf o Eiriau ar Alawon Cymreig', the first of four volumes (only one of which was published).

- He is sometimes referred to as 'the Robert Burns of Welsh poetry'.

- He was fascinated by Welsh folk songs and wrote lyrical poems to their rhythm. These included 'David of the White Rock' or 'Dafydd y Garreg Wen'.

Extract from 'Alun Mabon'

The mighty mountains changeless stand.

Tireless the winds across them blow;

The shepherd's song across the land

Sounds with the dawn so long ago.

Books

Conran, T. 2017. Welsh Verse. Wales. Seren. (See above photo.)

Links

Jones, D.G. The Dictionary of Welsh Biography. 1959. Hughes, John (Ceiriog) (Ceiriog; 1832-1887), poet.

Welsh Icons News. 2019. John Ceiriog Hughes.

Cafodd T.H. Parry-Williams ei eni yn Rhyd-Ddu, Eryri, a daeth o deulu o lenorion. Roedd ei dad, Henry Parry-Williams, wedi ennill clod yn yr Eisteddfod, ac roedd Ann, ei fam, yn chwaer i gynganeddwr uchel ei fri. Bardd adnabyddus ledled Cymru hefyd oedd R.Williams Parry, ac roedd yntau’n gefnder i T.H. Parry-Williams.

Mynychodd T.H. Parry-Williams Brifysgol Cymru, Aberystwyth, ble y daeth yn athro’n ddiweddarach. Aeth yn ei flaen i fynychu Coleg Iesu, Rhydychen ym 1909, gan astudio geiriau benthyg Saesneg yn y Gymraeg. Cyhoeddwyd yr ymchwil hwn o dan y teitl, ‘The English Element in Welsh’. Dim ond ym 1931 y cyhoeddwyd ei gyfrol gyntaf o farddoniaeth, ‘Cerddi’. Mae chwe chyfrol bellach o gerddi a thraethodau’n cynnwys y rhan fwyaf o’i waith creadigol, 'Olion' (1935), 'Lloffion' (1942), 'O'r Pedwar Gwynt' (1944), 'Ugain o Gerddi' (1949), 'Myfyrdodau' (1957) a 'Pensynnu' (1966). Cafodd y traethodau’u casglu at ei gilydd yn 'Casgliad o Ysgrifau’ ym 1984, a’r cerddi yn 'Casgliad o Gerddi' dair blynedd yn ddiweddarach.

Ysgrifennodd erthyglau academaidd, a daeth yn ffigwr adnabyddus ar y teledu a’r radio. Roedd e’n arfer chwarae rhan weithredol mewn cymdeithasau Cymraeg eu hiaith, yn cynnwys Llys yr Eisteddfod Genedlaethol, ac Anrhydeddus Gymdeithas y Cymmrodorion. Cafodd T.H. Parry-Williams ei urddo’n farchog ym 1958.

- Fel plentyn ysgol, dechreuodd ysgrifennu dyddiadur manwl, arfer y daliodd ato weddill ei oes.

- Roedd yn wrthwynebwr cydwybodol yn ystod yr Ail Ryfel Byd a chyhoeddodd gerddi yn y cylchgrawn heddychol, 'Y Deyrnas'.

- Ysgrifennodd mewn cwpledi sy’n odli, ac ar ffurf soned.

- Teithiodd yn eang; astudiodd ym Mhrifysgol Freiburg (yr Almaen), ac aeth e i Ogledd a De America, ymhlith mannau eraill.

T.H.Parry-Williams was born in Rhyd-Ddu, Snowdonia. He came from a literary family. Henry Parry-Williams, his father, had been successful in the Eisteddfod and Ann, his mother, was the sibling of a celebrated strict metre poet. T.H Parry-Williams’ first cousin, R. Parry-Williams, was also a well-known poet in Wales.

T.H Parry-Williams attended The University of Wales, Aberystwyth, where he later became a professor. He went on to attend Jesus College Oxford in 1909 studying English loan words in Welsh. This research was published in 1923 titled 'The English Element in Welsh'. His first volume of poetry, 'Cerddi', wasn’t published until 1931. A further six volumes of poems and essays make up the main body of his creative work, 'Olion' (1935), 'Lloffion' (1942), 'O'r Pedwar Gwynt' (1944), 'Ugain o Gerddi' (1949), 'Myfyrdodau' (1957) and 'Pensynnu' (1966). The essays were collected in 'Casgliad o Ysgrifau' in 1984, and the poems in 'Casgliad o Gerddi' three years later.

He wrote scholarly articles and became a well-known figure on television and radio. He was active in Welsh societies including the Court of the National Eisteddfod and The Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion. T.H Parry-Williams was knighted in 1958.

- As a schoolboy he started a detailed diary. A habit that he kept until his death.

- He was a conscientious objector during WWII and published poems in the pacifist journal, 'Y Deyrnas'.

- He wrote in rhyming couplets and sonnets.

- He was well-travelled having studied in Freiburg University (Germany) and travelled to South and North America, among others.

Darn oddi wrth 'Hon'

Beth yw’r ots gennyf i am Gymru? Damwain a hap

Yw fy mod yn ei libart yn byw. Nid yw hon ar fap

Yn ddim byd ond cilcyn o ddaear mewn cilfach gefn,

Ac yn dipyn o boendod i’r rhai sy’n credu mewn trefn.

Extract from 'This'

What do I care about Wales? It is just fluke and accident

That I live within her confines. She is no more on a map

Than a small patch of land in the back end of beyond.

And a bit of a pain to those who believe in order.

Books

Parry-Williams, T.H. 2011. Cerddi Rhigymau a Sonedau. Wales Gomer Press. (See above photo.)

Links

Evans, R. The Curious Astronomer. 2011. “Hon” (This) – a poem.

Price, A. Dictionary of Welsh Biography. 2018. Parry-Williams, Sir Thomas Herbert (1887-1975), author and scholar.

Cafodd Lynette Roberts ei geni ym Buenos Aires, yr Ariannin, i rieni o dras Cymreig. Astudiodd Gelf yn The Central School for Arts and Crafts, Llundain. Ym 1939, priododd y bardd o Gymro, Keidrych Rhys, ac ymgartrefodd yn Llanybri. Cyhoeddwyd ei dau gasgliad o gerddi, Poems (1944) a Gods with Stainless Ears: a Heroic Poem (1951) gan Faber and Faber. Roedd T.S. Eliot, golygydd i’r cwmni, yn edmygu’i gwaith.

Ysgrifennodd Lynette Roberts am fywyd pentrefyn Llanybri, yn cynnwys y bobl oedd yn byw ac yn gweithio yn y pentref. Mae’r pynciau yn ei cherddi’n cynnwys erthyliad a byd natur. Roedd ganddi ddiddordeb neilltuol mewn adar. Dylanwadwyd arni hi gan draddodiadau barddol Cymraeg, ac roedd hi’n eu defnyddio i fynegi’i phrofiadau ynghylch byw ar ffiniau pentref Cymraeg traddodiadol. Ym 1944, ysgrifennodd draethawd byr o’r enw ‘Village Dialect’ oedd yn mynegi’r brwdfrydedd hwn. Roedd arddull ei hysgrifennu’n arloesol, a dim ond yn ddiweddar y mae’i gwaith wedi derbyn y gydnabyddiaeth y mae’n ei haeddu. Mae barddoniaeth Lynette yn tynnu ar brofiad synhwyraidd dwys i ddangos bywyd yn y Gymru wledig yn ystod y cyfnod o ddatblygu technegol sylweddol a ddigwyddodd yn yr Ail Ryfel Byd. Gellir gweld esiampl o’r arddull hon yn ‘Air Raid on Swansea’ (1941). Mae’r gerdd yn cyfuno’i hiaith fywiog â’r arswyd technegol oedd wedi tarfu ar gefn gwlad llonydd Cymru.

Roedd Lynette Roberts a Robert Graves yn gohebu gyda’i gilydd. Yn aml byddai’r naill yn helpu’r llall i ddatblygu syniadau a cherddi. Roedd hi’n arfer ysgrifennu llythyrau personol a phreifat at y bardd Alun Lewis. Mae 'Poem from Llanybri' (1944) yn gwahodd Alun Lewis i ymweld â hi yn ei chartref yn Llanybri. Roedd hi’n ffrind i Elizabeth Sitwell, Vernon Watkins, a beirdd enwog o Gymru oedd yn ffynnu yn yr 20fed ganrif.

- Dylan Thomas oedd y gwas yn ei phriodas . Diddymwyd ei phriodas ym 1948.

- Yn hwyrach yn ei hoes, ymunodd â Thystion Jehofa.

- Ym 1956, torrodd ei nerfau, a threuliodd gyfnodau mewn ysbytai meddwl.

Lynette Roberts was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina from parents of Welsh ancestry. She studied Art at The Central School for Arts and Crafts, London. In 1939, she married Welsh poet Keidrych Rhys and settled in Llanybri. Her two poetry collections, Poems (1944) and Gods with Stainless Ears: a Heroic Poem (1951) were published by Faber and Faber, whose editor, T.S Eliot, was an admirer of her work.

Lynette Roberts wrote about village life in Llanybri, including the people who lived and worked in the village. The subjects of her poetry include miscarriage and the natural world. She was particularly interested in birds. She was influenced by Welsh poetic traditions and used them to express her experiences of living on the borders of a traditional Welsh village. In 1944, she wrote a short essay called 'Village Dialect' that expressed this enthusiasm. Her writing style was innovative and it is only recently that she has begun to receive the recognition that her work deserves. Lynette's poetry draws on an intense sensory experience to depict life in rural Wales during the technological burst that occurred during WWII. An example of this style can be seen in 'Air Raid on Swansea' (1941). The poem fuses her vibrant use of language with the technological terror that had descended upon the quiet countryside of Wales.

Lynette Roberts and Robert Graves exchanged correspondence, often assisting each other with the development of ideas and poems. She held an intimate correspondence with poet, Alun Lewis. 'Poem from Llanybri' (1944) is an invitation to Alun Lewis to visit her at home in Llanybri. She was friends with Elizabeth Sitwell, Vernon Watkins and other notable Welsh poets of the 20th century.

- Dylan Thomas was best man at her wedding. Her marriage dissolved in 1948.

- In later life she became a Jehovah’s Witness.

- In 1956 she suffered a mental breakdown and spent time in mental institutes.

Extract from 'Poem from Llanybri'

Then I'll do the lights, fill the lamp with oil,

Get coal from the shed, water from the well;

Pluck and draw pigeon, with crop of green foil

This your good supper from the lime-tree fell.

Books

Roberts, L. McGuinness, P (ed). 2005. Lynette Roberts Collected Poems. England. Carcanet Press. (See above photo.)

McAvoy, Siriol (ed). 2019. Locating Lynette Roberts: Always Observant and Slightly Obscure. Wales. University of Wales Press.

Wedi ei geni a’i magu yng Nghaerdydd, mae gwreiddiau teuluol Mererid Hopwood yn Sir Benfro. Wedi cael ei haddysg yn Ysgol uwchradd Llanhari ac yna ym Mhrifysgol Aberystwyth, aeth ymlaen i ddatblygu gyrfa fel ieithydd dawnus sy’n arbenigo mewn Sbaeneg ac Almaeneg. Yng nghanol y 1990au, gan dynnu ar ei dawn fel ieithydd, dysgodd gynganeddu mewn gwersi a sefydlwyd gan y Prifardd Tudur Dylan a Geraint Roberts, Ysgol Farddol Caerfyrddin.

Yn ddigon buan daeth yn agos at gipio’r Gadair yn Eisteddfod Ynys Môn, 1999 cyn mynd ymlaen i’w hennill yn Eisteddfod Genedlaethol Dinbych, 2001 – y fenyw gyntaf erioed i gyflawni’r gamp. Canodd awdl oedd yn trin deunydd na fu canu arno cynt yn hanes wrywaidd cystadleuaeth y gadair, sef y pwnc o feichiogi, geni babi ac yna’r brofedigaeth yn sgil colli’r plentyn. Aeth ymlaen wedyn i dorri record arall, drwy fod y fenwy gyntaf i wneud y trebl, sef ennill y Gadair, y Goron a’r Fedal Ryddiaith.

“Yn y darn rhwng gwyn a du

Mae egin pob dychmygu”

Mae Mererid, trwy ei gwaith fel academydd, darlledwr, Prifardd ac awdur wedi dod yn enw cyfarwydd i gynulleidfaoedd yng Nghymru a thu hwnt. Mae’r Prifardd Alan Llwyd wedi sôn am bwysigrwydd Symlder Dyfnder mewn mynegiant barddol ac mae canu Mererid yn ymgorffori’r cysyniad hwn gyda’i cherddi sydd ar y cyfan yn ddealladwy o’r darlleniad cyntaf gan lwyddo i gynnwys dyfnder athronyddol. Mae’n aelod disglair o staff Prifysgol Cymru Dewi Sant, wedi cyhoeddi nifer o lyfrau i blant a hefyd yn gwneud argraff yn ddiweddar gyda phrosiectau mawrion fel y gwaith comisiwn, Cantata Memoria, a grewyd ar y cyd gyda Karl Jenkins i gofio trychineb Aberfan, a’r sioe Eisteddfodol gyda Robert Arwyn a Bryn Terfel, i gofio Paul Robeson, ‘Hwn Yw Fy Mrawd’.

Mae Mererid Hopwood hefyd yn aelod blaenllaw o Gymdeithas y Cymod ac yn ymgyrchu’n angerddol dros heddwch.

- Enillydd y Gadair yr Eisteddfod Genedlaethol, Dinbych, 2001.

- Enillydd y Goron, Eisteddfod Genedlaethol Meifod, 2003.

- Cyhoeddodd ‘Singing in Chains’ (Gwasg Gomer), cyflwyniad i’r gynghanedd dryw gyfrwng y Saesneg yn 2004.

- Bardd Plant Cymru 2005-2006.

- Enillydd y Fedal Ryddiaith, Eisteddfod Genedlaethol Caerdydd, 2008.

- Cyhoeddodd 'Nes Draw’ (Gwasg Gomer), ei chyfrol gyntaf o gerddi, yn 2015.

Although born and brought up in Cardiff, Mererid Hopwood’s family roots are in Pembrokeshire. Having been educated in Llanhari secondary school and then in Aberystwyth University, she went on to pursue a career as a talented linguist specialising in Spanish and German. In the mid-1990s, drawing on her linguistic skill, she learned to fashion cynghanedd in classes established by the Chief-bard Tudur Dylan and Geraint Roberts, of Carmarthen Bardic School.

Soon enough she came close to seizing the Chair in the Anglesey Eisteddfod in 1999, before going on to win it in the Denbigh National Eisteddfod in 2001 – the first ever woman to achieve the feat. She composed an awdl (that is, an ode in strict metre), dealing with material that had not been touched upon previously in the masculine history of the chair competition, namely the topic of pregnancy, giving birth to a baby, and then the bereavement in the wake of losing the child. She then went on to break another record, by being the first woman to “win the triple” namely to win the Chair, the Crown, and the Prose Medal.

“In the spot between white and black

Are the buds of all imagining.”

Mererid, through her work as academic, broadcaster, Chief-bard and author, has become a familiar name to audiences in Wales and beyond. The Chief-bard Alan Llwyd has talked about the importance of the Simplicity of Depth in poetic expression, and Mererid’s composition embodies this concept in her poems which on the whole are comprehensible on the first reading, succeeding to contain philosophical depth. She is a dazzling member of staff at the University of Wales Trinity Saint David, having published a number of books for children, who is also making an impression lately with big projects such as the commissioned work, Cantata Memoria, which was created jointly with Karl Jenkins to commemorate the Aberfan disaster, and the Eisteddfod show with Robert Arwyn and Bryn Terfel, to commemorate Paul Robeson, ‘Hwn Yw Fy Mrawd’ (‘This Is My Brother’).

Mererid Hopwood is also a leading member of the Fellowship of Reconciliation (Cymdeithas y Cymod), and campaigns passionately for peace.

- Winner of the Chair in the National Eisteddfod, Denbeigh, 2001.