Pan o’n i’n blentyn ro’n i’n astudio hanes yn yr ysgol nes mod i’n bedwar ar ddeg (neu rywbeth fel hynny), a mwynhawn i ddysgu am Harri’r 8fed, ei wragedd i gyd, a’r mynachod; ac am Elisabeth y 1af, a’r holl gynllwynio a thorri pennau. Ond, ddysgais i erioed am hanes modern o gwbl. Wedi dweud hynny, ges i ‘yn magu yn Brynmill, Abertawe, a bron pob dydd pan o’n i’n grwt bach yr elwn i am dro gyda ‘yn Mam gan wibio o gwmpas gyda’r ddwy chwaer iau yn y gadair wthio. Ac wrth gwrs byddwn ni’n teithio drwy’r parciau ac ar lan y môr, lle mae’r Gwron Anhysbys yn gwarchod cymrawd anafus â reiffl, ar ben y gofeb i’r Ail Ryfel yn erbyn y Boeriaid yn Ne Affrica. Bob tro dweden ni helô hefyd wrth y ci achub enwog o’r enw ‘Swansea Jack’ a achubodd saith unigolyn ar hugain rhag boddi yn ôl y sôn. Ac wedyn, cyn cychwyn adre (lan rhiw yr holl ffordd yn ôl!), fe fydden ni’n chwarae’n rhydd o gwmpas y Senotaff, gan redeg lan a lawr, ac ymarfer darllen yr enwau sydd ar y waliau yno. Ond bellach, wi’n lico mynd i eistedd yn llonydd, a meddwl. Ac ar ôl hala cryn amser yn neud hynny yn ddiweddar, dyma gasgliad o’m meddyliau am y Rhyfel Mawr o safbwynt Cymru (ac Abertawe yn enwedig).

Dyma nodyn i’r darllenydd. Wi di dwlu ar ddod o hyd i wybodaeth ffeithiol gywir a diddorol mewn llyfrau ac ar y we (gobeithio!), y rhan fwya ohoni wedi’i chreu trwy waith caled iawn pobl eraill. Fodd bynnag, gan mai llawer o ffynonellau sydd, dyw ddim yn briodol cynnwys rhestr o adnoddau cynhwysfawr mewn erthygl gyffredinol o’r fath hon. Rhaid i fi ddiolchi’n fawr i’r awduron gwreiddiol, a chydnabod eu llafuriau.

When I was a child I studied history in school till I was fourteen (or something like that), and I enjoyed learning about Henry VIII, all his wives, and the monks; and about Elizabeth I and all the plotting and head-chopping. But, I never learned about modern history at all. Having said that, I was brought up in Brynmill, Swansea, and almost every day when I was a nipper I would go for a walk with me Mam, tearing about with my two younger sisters in the push-chair. And of course we’d go through all the parks and along the sea front, where the Unknown Soldier guards an injured comrade with a rifle, on top of the monument to the Second Boer War in South Africa. We’d always say hello, too, to the famous rescue dog called ‘Swansea Jack’ who save twenty-seven people from drowning if you believe the stories. And then, before turning homeward (uphill the whole way back!), we would play freely around the Cenotaph, running up and down, and practise reading the names on the walls there. But now, I like to go and sit in peace, and think. And after spending considerable time doing that lately, here’s a collection of my thoughts about the Great War from the vantage-point of Wales (and Swansea in particular).

A note to the reader. I’ve really enjoyed finding correct and interesting information in books and on the web (I hope!), most of it created through the very hard work of other people. However, because there are many sources, it is not appropriate to include a list of extensive resources in a general article of this type. I would like to give a give a big thank you to the original authors, and acknowledge their labours.

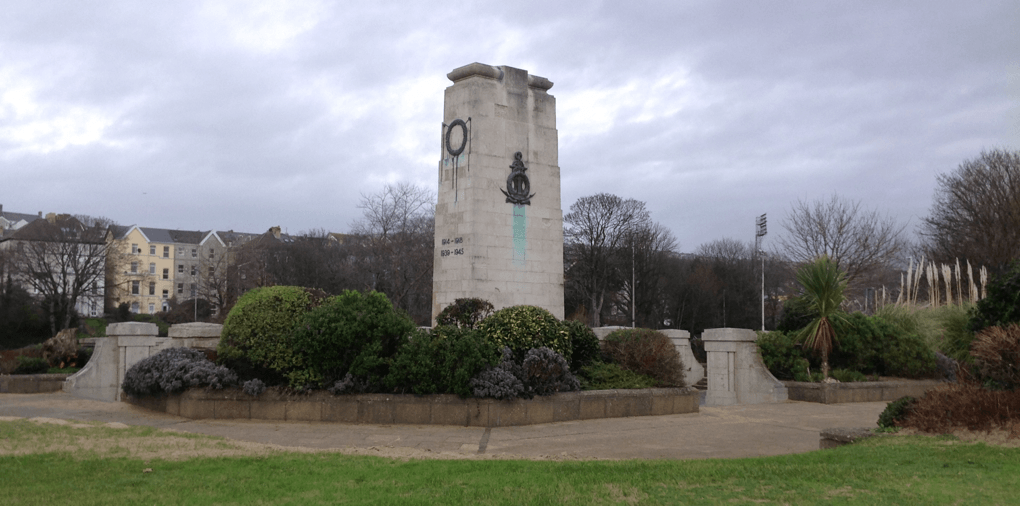

| 1af Ionawr y llynedd, ar drothwy’r flwyddyn newydd, rwy’n gwneud pererindod arbennig o’m tŷ, trwy fro fy mebyd yn Brynmill, Abertawe, i’r rhodfa ar hyd Heol y Mwmbwls. A dyna’r Senotaff, yn edrych yn ddigyffro dros y bae. Mae hwn yn enghraifft drawiadol o geufedd ar lun bedd gwag, mewn safle amlwg, ynghyd â’r gofgolofn sy’n anrhydeddu’r rhai a fu farw yn ystod amryw ryfeloedd, a gladdwyd yn rhywle arall. Tua phump o’r gloch ydy, wrth i fi sefyll ar bwys y rhithfedd yn y glaw mân, hallt, a thaenir yr awyr rudd fel lliain gwaedlyd ar yr orwel. | The 1st of January last year, on the threshold of the new year, I make a special pilgrimage from my house, through my boyhood haunts in Brynmill, Swansea, to the promenade alongside Mumbles Road. And there’s the Cenotaph, looking unconcernedly across the bay. This is a striking example of a war-memorial in the form of an empty grave, in an obvious location, together with the memorial column which honours those who died during various conflicts, who are buried elsewhere. It is about five o’clock, as I stand by the cenotaph in the salty drizzle, and the ruddy sky is spread like a blood-stained bandage on the horizon. |

| Mae gwawchio taer y gwylanod trahaus yn bygwth fy nrysu, a thry fy ymwybyddiaeth tuag at i mewn, tra crwydra fy llygaid ar draws enwau’r rheiny a gollwyd yn y Rhyfel Mawr. Ond beth y mae pobl o’m cenhedlaeth yn ei wybod am gynnen a dioddefaint? Plant oes yr atom ydym, a oedd yn arfer troi a throsi trwy’r nos gan boeni am gellwyriadau cuddiedig, neu am y dydd y câi’r ddaear gron ei llosgi’n lludw gan dân-belen. Ac felly y dechreua fy synfyfyrdod, llawn gwersi wedi’u dysgu a’u colli, yn y gobaith o allu esbonio ychydig o ran ein hanes i’m nith fach sydd yn ddeg oed — | The insistent squawking of the arrogant seagulls threatens to disturb my thoughts, and I turn my awareness inwards, while my eyes wander across the names of those who were lost in the Great War. But what do people of my generation know about strife and suffering? We are children of the atomic age, who used to toss and turn all night, worrying about hidden mutations, or about the day that the entire world would be bunt to a cinder by a fire-ball. And so I begin my meditation, full of lessons learned and lost, in the hope that I can explain a little of our history to my small niece who is ten years old – |

| Ryw ganrif yn ôl y cychwynnodd y Rhyfel Mawr yn Ewrop ag unig daniad, bradlofruddio, pall ar ddiplomyddiaeth, apelio at gytundebau astrus, cynigion terfynol rhwng cenhedloedd, a goresgyn gwledydd amhleidiol. Un o’r rhyfeloedd mwyaf marwol yn hanes y byd ydoedd, yr un fath i ymladdwyr ac i sifiliaid. Datblygiadau mewn technoleg a diwydiant a helpai i waethygu’r dinistr, yn ogystal ag ymladd mewn ffosydd a arweiniodd i sefyllfa annatrys. Ar ôl i’r dilyw o laid a gwaed lonyddu, digwyddodd dymchwelfa wleidyddol, ysgytwol, a chwyldroeon. | It was about a century ago that the Great War in Europe began with a single shot, an assassination, a failure of diplomacy, an appeal to obscure treaties, ultimatums between nations, and the invasion of neutral lands. It was one of the most lethal wars in the history of the world, both for combatants and civilians. It was developments in technology and industry that would help to worsen the destruction, as well as trench warfare which led to an unresolvable situation. After the flood of mud and blood had subsided, a shocking political upheaval, and revolutions, ensued. |

| Rwy’n edmygu’r garreg Portland ar y Senotaff, sy’n debyg i’r un a adeiladwyd gan Lutyens ger Senedd y Deyrnas Unedig ym Mhalas San Steffan yn Llundain. Dyna, mewn efydd, arfbeisiau Abertawe, torchau, angorau, placiau sy’n cofnodi enwau’r lladdedigion. A hyn oll o dan yr arysgrif Ladin, “Pro Deo Rege et Patria” – “Dros Dduw, Brenin, a Mamwlad.” Amgylchynir y caeadle â muriau wythonglog, ond difrodwyd y pedwar porth gan shrapnel yn ystod cyrchau awyr yn yr Ail Ryfel Byd, ac maent wedi'u tynnu ymaith oherwydd hyn. | I admire the Portland stone on the Cenotaph, which is similar to the one built by Lutyens by the Houses of Parliament in London. There are, in bronze, the arms of Swansea, wreaths, anchors, plaques that record the names of those killed. And all this beneath the Latin inscription, “Pro Deo Rege et Patria” – “For God, King, and Country.” The enclosure is surrounded by octagonal walls, but the four gates were destroyed by shrapnel during air-raids in the Second World War, and they have been taken away because of this. |

| Rhôi’r Rhyfel brawf ar ysbryd cenedlaethol Cymru, bron hyd at ddinistriad. Fodd bynnag, cadarnhawyd cydraddoldeb Cymru â rhannau eraill y Deyrnas Unedig, ac ag aelodau’r Ymerodraeth, mewn theori, o leiaf, pan grëwyd Gwarchodlu Cymreig, ac y 38ain Adran Troedfilwyr Cymreig. Symbylwyd yr ysbryd rhyfel yn y gwirfoddolwyr trwy apelio at syniadau gwrywdod fel dyletswydd, gwroldeb, bri, ofn Duw, a pharch at y Brenin. | The War would test Wales’s national spirit, almost to destruction. However, Wales’s equality with other parts of the United Kingdom, and with members of the Empire, was confirmed, in theory, at least, when Welsh Guards and the 38th Welsh Infantry Division were established. The war-spirit was stirred up in the volunteers by appealing to ideas of manliness such as duty, courage, prestige, fear of God, and respect for the King. |

| Ond, wrth imi lechu yma, a thywod yn fy llygaid, rwy’n gofyn i’m hun: a ddaw’r cyfrifoldeb o gofio i ben â’r seremonïau, y pabïau, y gweddïau? Erbyn hyn, ai cofio egwyddorion cyffredinol, digwyddiadau a chanlyniadau a wnawn yn hytrach na bywydau a phersonoliaethau’r unigolion? Pwy sy biau’r enwau hyn, pwy oedd y gwŷr (a gwragedd) hyn, y gwrol ryfelwyr, y gwladgarwyr tra mad, a gollasant eu gwaed dros ryddid? Beth yw ystyr y geiriau: byw, marw, aberthu? Lle rydym yn awr: lle y byddwn yn y dyfodol? Pwy fydd yn gwneud y dewisiadau, a sut, a pham? | But, as I lurk here, with sand in my eyes, I ask myself: does the responsibility of remembering come to an end with the ceremonies, the poppies, the prayers? By now, is it that we remember general principles, events and consequences, rather than the individuals’ lives and personalities? Who owns these names, who were these men (and women), the brave warriors, the most excellent patriots, who lost their blood for freedom? What is the meaning of the words: living, dying, sacrifice? Where are we now: where shall we be in the future? Who shall make the choices, and how, and why? |

| Nid oedd y mil o ddynion a ddaeth ynghyd y tu ôl i’r dafarn o’r enw “The George” yn y Mwmbwls yn filwyr proffesiynol. Tadau a meibion ydoedd, a chlercod banc, llafurwyr, glowyr, aelodi capeli, paffwyr a chwaraewyr rygbi. “Mêts Abertawe” oedd enw ar y criw hwn o frodyr erbyn iddynt gyrraedd Ffrynt y Gorllewin. Erbyn diwedd y Rhyfel y byddai mwy na 600 ohonynt wedi cael eu colli. Mae Llechres Anrhydedd yn rhestru enwau 2274 o eneidiau o Abertawe a fu farw yn y Rhyfel, a chleddyfau cyfiawnder yn eu dwylo, ond nid ydwyf yn bwriadu eu cyfrif nhw i gyd. | The thousand men who gathered outside the pub named “The George” in the Mumbles were not professional soldiers. They were fathers and sons, and bank clerks, labourers, miners, chapel members, boxers and rugby-players. “The Swansea Pals” was the name of this band of brothers by the time they reached the Western Front. By the end of the War, more than 600 of them would have been lost. The Roll of Honour lists the names of 2274 souls from Swansea who died in the War, the swords of justice in their hands, but I do not intend to count them all. |

| Yn y Rhyfel hwn, y ddwy fyddin oedd biau’r un grym tanio, ond ni allent wthio yn eu blaen nac ennill tir o achos y ddaearyddiaeth. Cloddiwyd ffosydd ar hyd blaen y gad, wedi’u hamddiffyn â weiren bigog, ac â ffrwydryddion. Diogelai’r rhain yr ymladdwyr rhag gynnau a chanonau. Rhwng y ddau ffrynt oedd tir neb, a oedd yn agored i ymosod o'r ddwy ochr. | In this War, both armies possessed the same fire-power, but they could not push forward, nor gain territory because of the geography. Trenches were dug along the battle-front, defended with barbed-wire, and with explosives. These protected the fighters from guns and cannons. Between the two fronts was no-man’s-land, which was open to attack from both sides. |

| Arweiniai’r sefyllfa anhydrin hon i ryfel athreuliol, llawn seithuctod. Yr amddiffynwyr a fanteisiai ar yr ymosodwyr, a bu’r bombardio di-baid yn achos colled milwyr a defnyddiau, a flinai’r gelyn. Yr enillwyr a fyddai biau mwy o adnoddau. Delwedd ddiffiniol y Rhyfel Mawr yw golygfa lle y mae lliaws dynion ieuainc, dewr yn mynd dros ymyl y ffos er mwyn ymosod ar y gelyn ymysg crochan uffernol llawn tân, llaid, gwaed a gweiddi. Hyd yn oed ymosodiadau llwyddiannus a olygai ladd torfol. | This intractable situation led to a war of attrition, full of frustration. The defenders had the advantage over the attackers, and the ceaseless bombardment caused the loss of soldiers and provisions, which debilitated the enemy. The winners would be those who had more resources. The defining image of the Great War is a scene where a host of young, brave men goes over the top of the trench to attack the enemy in a hellish cauldron full of fire, mud, blood, and shouting. Even successful attacks would mean mass slaughter. |

| Mae Coed Mametz ar frig tyle serth, yng nghanol tir agored llawn pantiau. Ac yno yr ymosododd y milwyr Prydeinig ar yr Almaenwyr yng Ngorffennaf 1916. Yn gyntaf oll, yn rhyfeddol, ymddangosai na fyddai unrhyw wrthsafiad. Sut bynnag, wrth i’r dynion nesáu, trawsant ar ymosodiad parhaus a marwol o saethu drylliau peiriannol. Cyrcydai’r goroeswyr mewn tyllau yn y ddaear, er mwyn osgoi’r bwledi. Disgynnodd yr Almaenwyr, a dechreuodd ymladdfa ddryslyd â dyrnau a bidogau ymhlith y coed wedi’u difetha, y ceudyllau, y llaid, y weiren bigog, y ffosydd, a’r cyrff. | Mametz Wood is at the top of a steep hill, in the middle of open ground full of hollows. And there the British soldiers attacked the Germans in July 1916. First of all, strangely, it appeared that there would be no resistance. However, as the men got nearer, they hit upon a sustained and deadly onslaught of machine-gun fire. The survivors cowered in holes in the ground to avoid the bullets. The Germans descended, and there began hand-to-hand fighting with bayonets amidst the devastated trees, the craters, the mud, the barbed-wire, and the corpses. |

| Bu bron i’r Almaenwyr gael eu hyrddio yn eu hôl, ond wrth iddi nosi, daeth yn amhosib penderfynu pwy oedd pwy. Bombardiai’r ddwy fyddin faes y frwydr, a saethai’r milwyr gyfaill a gelyn yn ddiwahân mewn dychryn. Er hyn oll, y Prydeinwyr a drechodd yn y pendraw. Pedair mil o Gymry a laddwyd yno, yn cynnwys cant o Abertawe. Heddiw, saif cerflun y Ddraig Goch yn herllyd ger Mametz, er gof am lewder a phenderfyniad gwyllt y milwyr Cymreig colledig. | The Germans were almost pushed back, but as night fell, it became impossible to decide who was who. Both armies bombarded the battle-field, and soldiers shot friend and enemy alike in terror. Despite all this, it was the British who prevailed in the end. Four thousand Welsh were killed there, including a hundred from Swansea. Today, a statue of the Red Dragon stands defiantly near Mametz, in memory of the bravery and wild determination of the lost Welsh soldiers. |

| Grymoedd Prydain a ddarluniai eu hun yn wŷr bonheddig, llawn glewder a rhagoriaeth foesol; wrth gwrs mai’r gwrthwynebwr a wnaethai’r un peth yn union. Ond, bydd rhaid inni ofyn: ai angenfilod drygionus oedd yr Almaenwyr i gyd? Nage ddim! Gallwn gyfeirio at brofiad Robert Evans o Ddolgellau, oedd yn aelod o Gorfflu Meddygol Brenhinol y Fyddin. Er ei syndod, pan aeth ef gyda milwyr eraill i gasglu clwyfedigion a oedd wedi gorwedd yn nhir neb am ddyddiau, daeth rhai o’r gelynion allan o’u ffosydd a helpu i gladdu’r meirwon yn hytrach na thanio arnynt. | The British forces depicted themselves as gentlemen, full of courage and moral superiority; of course the adversary did exactly the same thing. But, we must ask: were all the Germans monsters of iniquity? Definitely not! We can refer to the experience of Robert Evans from Dolgellau, who was a member of the Royal Army Medical Corps. To his surprise, when he went with other soldiers to collect wounded men who had been lying in no-man’s-land for days, some of the enemy came out of their trenches and helped to bury the dead rather than firing at them. |

| Dim ond hanner y dynion dewr a ddeuai yn ôl o Ffrynt y Gorllewin yn fyw ac yn iach. Aeth tua 300,000 o Gymry i'r gad, a bu farw tua 40,000 ohonynt. Yr ieuaf oedd George Lewis o’r Bari, hogan gweini yn y Llynges Frenhinol, a foddodd yn 14 oed. Preifat Owen Owen oedd y milwr cyntaf o Abertawe a fu farw. Fe’i boddwyd yn nociau Abertawe wrth iddo fod ar ddyletswydd ym Medi 1914. | Only half the brave men would come back from the Western Front alive and well. About 300,000 Welshmen went to war, and about 40,000 of them died. The youngest was George Lewis of Barry, a serving-boy in the Royal Navy, who drowned at 14 years of age. Private Owen Owen was the first soldier from Swansea who died. He was drowned in Swansea docks while he was on duty in September 1914. |

| Gosodwyd y garreg sylfaen i’r Senotaff gan y Cadlywydd Haig, Iarll Bemersyde, a oroesai’r rhyfel o leiaf. Oedd Haig, yn neilltuol, yn “gigydd” didostur a anfonai “llewod wedi’u dwyn gan fulod” i gael eu lladd heb resymeg? Ai ymhyfrydu yn tywallt gwaed a wnaeth? Wedi’r cwbl, Prydain a enillodd: ond, a ba gost? Dyna ddadl nas torrwyd heddiw. Wedi dweud hyn, ddydd y cadoediad y lladdwyd neu anafwyd tua 10,000 o ddynion, yn cynnwys Corporal Stephen Lamont o Abertawe. Fe’u hanfonwyd i farw gan y cadlywyddion a wyddai y byddai’r rhyfel yn dod i ben am 11 o’r gloch y bore. | The Cenotaph’s foundation stone was laid by Field Marshal Haig, Earl of Bemersyde, who survived the war at least. Was Haig, in particular, a ruthless “butcher” who sent “lions led by donkeys” to get killed for no reason? Is it true that he rejoiced in spilling blood? After all, it was Britain who won: but, at what cost? That is a debate that has not been resolved today. Having said that, it is on the day of the armistice that 10,000 men were killed or wounded, including Corporal Stephen Lamont of Swansea. They were sent to their deaths by the generals who knew that the war would come to an end at 11 o’clock that morning. |

| A oedd y Rhyfel naill ai’n fenter ofer ac afradlon, neu ynteu’n anghenraid anochel? Erys hyn yn fater i'w drafod. Mae rhaid inni’n rhwystro’n hunain rhag archwilio digwyddiadau doe â synnwyr heddiw. Roedd amgylchiadau’r Rhyfel Mawr yn arbennig o anodd, ac yn wir y methai’r cadlywyddion ymaddasu i’r rhain yn ddiymdroi. Y ffaith amdani yw na lwyddai rhyfela mewn ffosydd i gyflawni ei nodau, ac oherwydd hyn y dyfeisiwyd magnelaeth well, nwyon mwy gwenwynig a thanciau. Mawr oedd rhoddion y Rhyfel Mawr. | Was the War a futile and extravagant venture, or an unavoidable necessity? This remains a matter for discussion. We must restrain ourselves from investigating the events of yesterday with the sensibilities of today. The circumstances of the Great War were especially difficult, and certainly the generals failed to adapt themselves to these immediately. The fact of the matter is that fighting in trenches did not succeed to achieve its aims, and it is because of this that better artillery, more poisonous gases, and tanks, were devised. Great were the gifts of the Great War. |

| Achosai’r Rhyfel dlodi a chyni i’r rheiny a adawyd yn y famwlad, hefyd. Erbyn diwedd y Rhyfel y byddai’r mwyafrif o deuluoedd wedi colli rhyw berthynas, a difethwyd rhai cymunedau’n llwyr. Gwasgai posteri propaganda ar bobl gartref i gefnogi’r ymdrech ryfel. Roedd rhai’n gofyn, “Beth wnaethoch chi yn ystod y Rhyfel Mawr, Dada?”, tra oedd eraill yn datgan, “Yn wir – Buddugoliaeth lwyr os bwytewch lai o fara.” Ar ddechrau’r Rhyfel, daeth chwarter mil o ffoaduriaid o Ffrainc a Gwald Belg i Brydain, ac aeth llawer ohonynt i Abertawe gan ymuno â chymuned gynfodol yno. Fodd bynnag, triniwyd estroniaid preswyl o’r Almaen yn wael gan y Prydeinwyr bryd hynny. | The War caused poverty and adversity to those who were left in the homeland, too. By the end of the War, the majority of families would have lost some relative, and some communities were destroyed entirely. Propaganda posters entreated people at home to support the war effort. Some asked, “Daddy, what did you do during the Great War?”, while others declared “Yes – Complete victory if you eat less bread.” At the start of the War, a quarter of a million refugees came to Britain from France and Belgium, and many of them went to Swansea, joining an already-existing community there. However, resident aliens from Germany were treated badly by the British at that time. |

| Gofalai’r menywod am y plant, ac roedd rhaid iddynt wneud swyddi’r dynion a frwydrai ar ben hynny. Gweithient i swyddfeydd post, ffatrïoedd, gweithleoedd arfau rhyfel, ffermydd, busnesi, a chwmnïoedd cludiant cyhoeddus. Bu bron i bob tylwyth golli aelod y teulu rywsut neu’i gilydd. | The women cared for the children, and they had to do the jobs of the men who were fighting on top of that. They worked in post-offices, factories, munitions factories, farms, businesses, and public transport companies. Almost every clan lost a family-member, one way or another. |

| Serch hynny, credid y gallai “cryd khaki” orlethu menywod a ddymunai garu gyda milwyr tramor. Felly y gorfodwyd cwrffyw, ac arestiwyd gwragedd a gyhuddwyd o gyflawni “gweithredoedd anweddus.” Ystyriwyd Abertawe’n “lle drygioni,” a lansiwyd “crwsâd dros burdeb” er mwyn rhwystro’r llanw o anfoesoldeb a ysgubai dros y dref yn ôl y sôn. A gyrhaeddodd yr ymgyrch hon ei nodau neu beidio, ym 1915 ymatebai rhai menywod i’r Rhyfel gan gychwyn Sefydliad y Merched yn Llanfairpwll. | Despite that, it was believed that “khaki-fever” overcome women who wanted to make love to overseas soldiers. So, a curfew was imposed, and women accused of indulging in “indecent acts” were arrested. Swansea was considered to be a “hotbed of immorality” and a “purity crusade” was launched in order to dam the tide of immorality that was apparently inundating the town. Whether this effort achieved its goals or not, in 1915 some women responded to the War, starting the Women’s Institute in Llanfairpwll. |

| Ymhellach, pan godwyd Senotaff Abertawe, dodwyd swllt y Brenin o dan y garreg sylfaen gan Mrs Fewings, oedd yn cynrychioli gweddwon milwyr. Unigryw yng Nghymru yw’r cofadail hwn, gan mai enwau 10 o wragedd sydd arno. Lladdwyd y rhan fwyaf ohonynt wrth weithio yn y gweithfeydd gwneud arfau ym Mhen-bre. Heddiw, gosodir lilïau gwynion ar y gofeb yn symbol o heddwch. | Furthermore, when Swansea Cenotaph was erected, the King’s shilling was placed under the foundation-stone by Mrs Fewings, who was representing the soldiers’ widows. Unique in Wales is this memorial, since the names of 10 women are on it. The majority of them were killed while working in the armaments works in Pembrey. Today, white lilies are placed on the monument as a symbol of peace. |

| Daeth cynhyrchu glo yng Nghymru i anterth ym 1913, ond tua dechrau’r Rhyfel datblygai cryn gwynion dros gyflogau ymhlith y glowyr. Wrth gwrs dibynnai’r Llynges Frenhinol, a’r diwydiant arfau ar gyflenwad cyson o lo. Fel canlyniad, daeth mynd ar streic yn dramgwydd troseddol erbyn haf 1915. Tua chwarter miliwn o lowyr wedi’u hysgogi gan ymdeimlad o anghyfiawnder a heriodd y gyfraith newydd. | Coal production in Wales reached its peak in 1913, but towards the start of the War, considerable complaints were building up amongst the miners over wages. Of course the Royal Navy, and the arms industry, depended on a constant supply of coal. As a result, going on strike became a criminal offence by the summer of 1915. About a quarter of a million miners, motivated by a feeling of injustice, challenged the new law. |

| Mae’n debyg bod llawer o’r dynion yn credu eu bod yn ddewr gan fynnu’u hawliau yn ystod cyfnod o berygl cenedlaethol. Yn wir, datganent, “Nid oes bradwr yn y tŷ hwn.” Eto i gyd, ystyrid bod y Rhyfel yn ffrae anghyfiawn rhwng y dosbarthiadau rheoli Ewrop gan rai. Felly roedd deffro o ymwybod sosialaidd: ar ôl chwyldro byd-eang, gobeithid y byddai’r gweithwyr yn uno er mwyn cymryd y llyw, gan reoli diwydiant a chymdeithas. Gorfodwyd Lloyd George ei hun i gwrdd â’r streicwyr, er iddo ildio i’r rhan fwyaf o’r hawliadau. | It is likely that many of the men believed that they were brave to insist on their rights during a period of national danger. Indeed, they declared, “There’s no traitor in this house.” Then again, it was considered by some that the War was an unjust squabble between Europe’s ruling classes. So, there was an awakening of socialist consciousness: after world-wide revolution, it was hoped that the workers would unite in order to take command, overseeing industry and society. Lloyd George himself was forced to meet the strikers, although he yielded to most of their demands. |

| Pan ddeuai’r milwyr adref, cyfarfyddent ddiweithdra, prinder tai, a chostau byw uchel. Mewn gwirionedd, dyma oedd Prydain yn dechrau colli ei lle fel pwerdy economaidd y byd. Dechreuodd diwydiant trwm, yn cynnwys codi glo, ddirywio, a symudodd llawer o weithwyr i Loegr gan chwilio am swyddi. Dim ond tair blynedd wedi diwedd y Rhyfel, roedd ffyniant glo wedi darfod. Roedd sefyllfa menywod yng Nghymru’n waeth byth nag amgylchiadau menywod yng ngweddill y Deyrnas Unedig. Ar ôl y Rhyfel, gostyngai’r nifer o fenywod oedd yn gweithio’n fwyfwy, yn enwedig ym maes amaethyddiaeth. | When the soldiers came home, they encountered unemployment, a lack of housing, and a high cost of living. In truth, this was a Britain starting to lose its place as the world’s economic powerhouse. Heavy industry, including coal-mining, began to deteriorate, and many workers moved to England looking for jobs. Only three years after the end of the War, the flourishing of coal had ceased. The situation of women in Wales was even worse than the circumstances of women in the rest of the United Kingdom. After the War, the number of women working dropped more and more, especially in the field of agriculture. |

| Roedd y Rhyfel yn drychineb i Gymru, a ddioddefai’n anghyfartal o’i chymharu â gweddill y Deyrnas Unedig, ac roedd yr ôl-effeithiau’n arwyddocaol iawn yn hanes y wlad. Yn y byd gwleidyddol, chwalwyd gafael y Blaid Ryddfrydol yn un o’i chadarnleoedd, wrth i nerth y Sosialwyr gynyddu. Cyfranogai gwerinoedd Prydain brofiadau ingol, tebyg, a thrwy hyn y cymysgai hunaniaethau cenedlaethol. Gofynnai pobl lle roedd Duw yn y ffosydd, yr Uffern honno ar y ddaear, a pan atebai rhai, “ar drai ar orwel pell mae ef,” y canlynodd argyfwng ffydd. Yng Nghymru, ansicrwydd a gofid a ddisodlai hunanhyder a gobaith, a nodweddion diffiniol o Gymreictod, megis iaith, crefydd, a chymdogaeth dda a wanhâi. | The War was a disaster for Wales, which suffered disproportionately compared with the rest of the United Kingdom, and the after-effects were highly significant in the history of the land. In the political sphere, the Liberal Party’s grip was shattered in one of its strongholds, while the strength of the Socialists increased. The folk of Britain partook of similar, distressing, experiences, and through this, national identities became entwined. People asked where was God in the trenches, that Hell on earth, and when some answered, “his glory’s ebbing away in the far distance,” then there followed a crisis of faith. In Wales, uncertainty and affliction displaced self-confidence and hope, and defining characteristics of Welshness, such as language, faith, and neighbourliness, became weaker. |

| Roedd y Cymry a’r Saeson yn chwedleua’n wahanol am y Rhyfel Mawr. Dyna gan fod paradocs yn ymwybyddiaeth gasgliadol y Cymry. Ar y naill law y gallent, fel deiliaid o’r Ymerodraeth Brydeinig, dderbyn eu bod yn brwydro dros Brydain. Ar y llaw arall, roedd llawer ohonynt wedi’u dadrithio gan gyfranogi o Ryfel Lloegr a fradychai gymuned, ffydd, heddwch, gwrth-filitariaeth a Chymreictod. Diddorol ydy mai Cymro oedd y gwrthwynebydd cydwybodol cyntaf i’w etholi’n Aelod Seneddol yn Llundain ar ôl y Rhyfel. Ac wedyn sefydlwyd Plaid Cymru yn y 1920au. Hefyd, synnwyr cenedligrwydd a ymgodai drwy Ewrop yr adeg honno, a fyddai’n difetha’r Ymerodraeth yn y diwedd. | The Welsh and the English wove different tales about the Great War. That is because there was a paradox in the Welsh collective consciousness. On the one hand, they could, as subjects of the British Empire, accept that they were fighting for Britain. On the other hand, many of them were disillusioned by partaking in the English War which betrayed community, faith, peace, anti-militarism, and Welshness. It is interesting that a Welshman was the first conscientious objector to be elected as a Member of Parliament after the War. And then Plaid Cymru was established in the 1920s. Also, feelings of nationalism arose throughout Europe at that time, which would destroy the Empire in the end. |

| Nid rhyfel tebyg i un a fu o’i flaen nac ar ei hôl oedd y Rhyfel Mawr. “Rhyfel i orffen pob rhyfel” ydy’r enw a roed iddo, hynny yw, “rhyfel yn erbyn rhyfel ei hun.” Yn sgil y gwrthdaro, bu newidiadau dros y byd i gyd. Yn y Gynhadledd Heddwch ym Mharis ym 1919, cadarnhawyd cytundebau, gosodwyd amodau, ail-leolwyd ffiniau, ailddosbarthwyd gwladfeydd, a chrëwyd a dibennwyd cenhedloedd. Fe ddylai Cynghrair y Cenhedloedd newydd ei sefydlu, fod wedi diogelu rhag rhyfel byd arall. | The Great War was not a war like any other that had been before, nor after it. “A War to end all war” is the name that was given to it, that is, “a war against war itself.” In the wake of the conflict, there were changes across the entire world. In the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, treaties were agreed, conditions were placed, boundaries were relocated, settlements were redistributed, and nations were created and liquidated. The newly-established League of Nations should have safeguarded against another world war. |

| Fodd bynnag, efallai mai “heddwch i roi pen ar heddwch i gyd” ydoedd yn wir. Canlyniadau seicolegol ac ymarferol i’r Rhyfel Mawr, sef dirwasgiad economaidd ac ymchwydd o genedlaetholdeb oddi mewn i genedl-wladwriaethau gweinion, a heuodd hadau’r Ail Ryfel Byd. Ni allai’r byd roi'r gorau i ymladd, a dechreuodd y rhyfela unwaith eto, ddim ond ugain mlynedd yn ddiweddarach. Nid oes angen dweud nad ydy’r gyflafan wedi peidio hyd yn hyn. | However, perhaps in fact it was a “peace to bring an end to all peace.” It was psychological and practical results of the Great War, namely economic depression and a surge of nationalism within weak nation-states, which sowed the seeds of the Second World War. The world could not give up fighting, and the hostilities began once again, only twenty years later. Needless to say, the slaughter has not abated even now. |

| Ni ddylem byth anghofio dydd Iau 4ydd Awst 1914, na dydd Llun 11eg Tachwedd 1918 ychwaith. Cynhelir Sul y Cofio bob blwyddyn rhag inni anghofio’r holl golled bywyd, yr aberthau, a’r cadoediad gwreiddiol. Hwyrach na ddiflanna’r pabïau cochion byth o feysydd cad gogledd Ewrop, lle y tyfant yn naturiol yn y pridd gwaedlyd. Ac ar hyn o bryd y cyrhaeddwn ddiwedd canmlwyddiant y Rhyfel Mawr. Mae’r byd heddiw yn wahanol o ran rhai pethau, ond mae’r un fath yn union â’r hen drefn ar lawer cyfrif pwysig eraill. Bellach, yr ydym yn brwydro rhyfeloedd yn erbyn cyffuriau, brawychiaeth, a thlodi yn ein mamwlad ein hunain, neu felly y dywedir wrthym. | We should never forget Thursday 4th August 1914, nor Monday 11th November 1918 either. Remembrance Sunday is held each year lest we forget all the loss of life, the sacrifices, and the original armistice. Perhaps the red poppies will never disappear from the battlefields of northern Europe, where they grow naturally in the bloody soil. And now we are reaching the end of the Great War’s centenary. The world today is different in some respects, but it is exactly the same as the old dispensation in many other important ways. Now, we are fighting wars against drugs, terrorism, and poverty, in our own homeland, or so we are told. |

| Nid un goroeswr o’r Rhyfel Mawr, yr oes mor ddreng honno, sydd yn ôl yn awr, a all draethu arswyd ac ehofnder y ffosydd: sawr y fan lle rhedai'r llygod mawr, sŵn yr ymladd, gwaeddi’r bechgyn, gwaed wedi’i gymysgu â glaw. Wedi diflannu y mae’r plac o brif stand San Helen, a arferai ddatgan “cof anfarwol” y meirwon. Erbyn hyn, pethau mud ydynt, a’u bysedd glas, sy wedi gadael tir y byw a chysur henaint. Efallai, rywbryd, y bydd hiraeth mewn distawrwydd arnom am eu lleisiau, eu cyngor, eu nerth, yng Nghymru o leiaf. | Not one survivor of the Great War, that age of such perversity, remains now, who can recount the terror and fearlessness of the trenches: the stench of the place where rats scurried, the sound of the fighting, the boys’ shouting, the blood mixed with rain. The plaque has disappeared from the main stand at Saint Helen’s, which used to declare the “immortal memory” of the dead. By now, they are dumb things, with lifeless fingers, which have left the land of the living and the comforts of old-age. Perhaps, sometime, we will long inconsolably in silence for their voices, their counsel, their strength, in Wales at least. |

| O ystyried manylion yr arwyr ar y Senotaff, mae’n fy nharo fod natur ddynol yn gallu bod mor wrthnysig. Ni allwn benderfynu ai ffeithiol ai dyfeisgar yw hanes; ai rhesymu ai chwedleua sy’n ei rheoli. Rydym yn dysgu o hanes, ond yn gwneud yr un camgymeriadau drosodd a throsodd. Rydym yn dathlu torri hen gelwyddau allan trwy drawsblannu rhai newydd. Ond mae’r amser i ryfel wedi mynd; bellach y mae angen inni ddiwygio’r gorffennol. Wrth i fysedd dyfal awel y gaeaf blagio’n ddi-baid y pabïau artiffisial, mae’r enwau’n galw arnaf yn gryf o hyd. Gorffwysent mewn hedd yn oes oesoedd, ond caffent, yn anad dim, gyfiawnder gennym, bron chwarter ffordd trwy’r 21ain ganrif hon — | Considering the details of the heroes on the Cenotaph, it strikes me that human nature can be so perverse. We cannot decide whether history is factual or fantastic; whether reasoning or tale-telling governs it. We learn from history, but make the same mistakes over and over. We celebrate cutting out old lies by transplanting new ones. But the time for warring has gone: now there is need for us to make good the past. As the winter breeze’s persistent fingers ceaselessly harass the artificial poppies, the names call to me strongly still. May the rest in peace forevermore, but, more than all else, may they have justice from us, a quarter of the way through this 21st Century — |

https://drive.google.