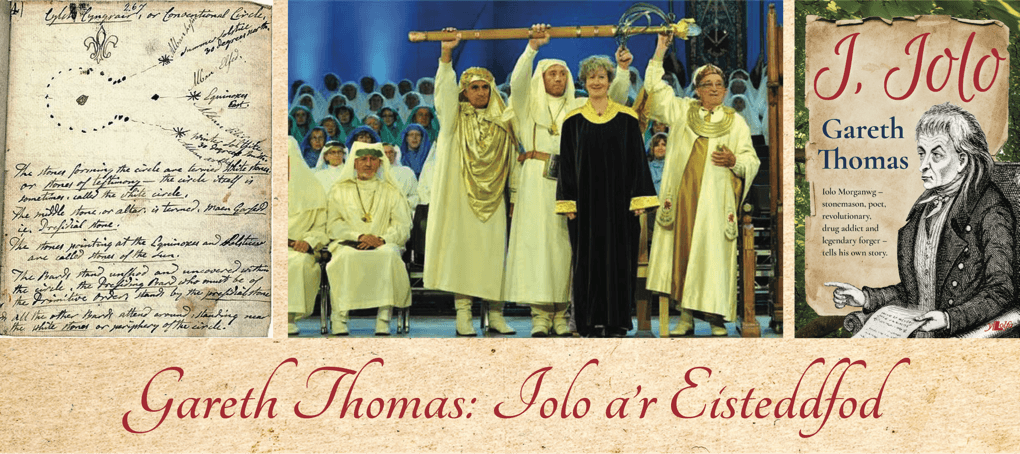

Nid Iolo Morganwg a gychwynnodd yr Eisteddfod Genedlaethol- mae gan honno wreiddiau cynharach o lawer yn ymrysonau'r beirdd a drefnid mewn cestyll mawr neu neuaddau ysblennydd lle roedd y beirdd yn cystadlu i ysgrifennu cerddi canmoliaethus er clod i ba arglwydd bynnag fyddai'n darparu’r wledd a’r llety. Ond beth yw tarddiad yr Eisteddfod a pha rôl y gwnaeth Iolo ei chwarae? Yma mae Gareth Thomas, awdur y nofel ffuglen hanesyddol Myfi, Iolo, yn esbonio mwy...

Iolo Morganwg did not start the National Eisteddfod- that has much earlier origins in bardic competitions organised in great castles or halls where poets competed to write flattering verses in praise of whichever Lord was providing the feast and lodging. But what are the origins of the Eisteddfod and what role did Iolo play? Here Gareth Thomas, author of the historical fiction novel I, Iolo, explains more...

| Ni ddechreuodd Iolo Morganwg yr Eisteddfod Genedlaethol. Cafodd hwnnw wreiddiau cynharach a llawer ohonynt mewn ymryson y beirdd a drefnid mewn cestyll mawr neu neuaddau ysblennydd lle roedd y beirdd yn cystadlu i ysgrifennu barddoniaeth a cherddi sebonllyd o glod i bwy bynnag arglwydd oedd yn darparu’r wledd a’r lletygarwch. Mae’n debyg y cafodd yr Eisteddfod gyntaf ei chynnal gan yr Arglwydd Rhys yng Nghastell Aberteifi, Nadolig 1176. Prin yw cofnodion ynglyn â’r oesoedd canol ond cynhaliwyd Eisteddfod fawr yng Nghaerfyrddin ym 1450. Roedd hwn ac eraill yn annhebyg i’r Eisteddfodau modern oherwydd absenoldeb cynulleidfa gyhoeddus. Y barnwr oedd y cwsmer, sef yr arglwydd oedd yno i’w canmol gan y beirdd. | Iolo Morganwg did not start the National Eisteddfod. That has much earlier origins in bardic competitions organised in great castles or splendid halls where poets competed to write flattering verses and songs in praise of whichever Lord was providing the feast and lodging. The first major Eisteddfod is thought to have been arranged by the Lord Rhys in Cardigan Castle at Christmas 1176. Few records survive from the middle ages but we know there was also a large Eisteddfod in Carmarthen in 1450. This and others were unlike modern Eisteddfods in that there was no public audience. The judge was the client, that is, the Lord the bards were there to please. |

| Yng Nghrwys, Sir Fflint ym 1568 cynhaliwyd math newydd o Eisteddfod am bwrpas penodol. Er bu cystadlaethau a gwobrau o gadair fach arian i’r bardd buddugol a thelyn arian i’r cerddor gorau, roedd nod ychwanegol. Dan awdurdod Elizabeth I safwyd Comisiwn Brenhinol i arholi bob bardd a oedd wedi cyflwyno ei hun fel ymgeisydd. Arwyddwyd trwyddedau i’r rhai oedd wedi llwyddo i brofi eu dilysrwydd fel beirdd o safon ddigonol i weithredu fel beirdd proffesiynol. Roedd y rhai oedd yn teithio’r wlad heb drwydded dilys yn cael eu categoreiddio fel cardotiaid a gallent gael eu troi ymaith neu ar y gwaethaf, eu carcharu neu waeth. | At Caerwys, Flintshire in 1568 a new style of Eisteddfod was arranged with a very particular purpose. Although there were competitions and the award of a silver chair to the winning bard and a silver harp to the best harpist, there was an additional purpose. A Royal Commission with the authority of Elizabeth I examined all poets who presented themselves as candidates and issued licences to those who had succeeded in establishing their claim to be of a high enough standard to practise as professional bards. Those travelling the land without a valid license were classified as beggars and could be turned away or, in the worst case, imprisoned or worse. |

| Parhaodd yr Eisteddfod yn y 18fed canrif fel traddodiad lleol yn hytrach na thraddodiad ranbarthol neu genedlaethol. Cafodd yr Eisteddfod ddiwygiad poblogaidd ar ddiwedd y ganrif gyda chyfres o Eisteddfodau mawr yng Ngogledd Cymru. Noddwyd y rheini gan ddynion busnes llwyddiannus y Cymry Llundain a Chymdeithas Y Gwyneddigion. Darparwyd gwobrau, medalau a lluniaeth digon deniadol i ddenu beirdd a thelynorion o bell. Am sbel cynhaliwyd Eisteddfod y Gwyneddigion yn flynyddol gan ddechrau yng Nghorwen ym 1789, ac wedyn i Lanelwy, Llanrwst a Dinbych. Er diwedd haelioni’r Gymry Llundain, roedd dadeni wedi ei thanio ym marddoniaeth a cherddoriaeth Cymraeg. Dechreuodd llu o Eisteddfodau rhanbarthol sylweddol faint ledled Cymru, yn ddibynol ran amlaf ar nawdd ariannol y boneddigion lleol. | During the 18th century the Eisteddfod continued as a local rather than regional or national tradition. The Eisteddfod began a popular revival at the end of the century when a series of large Eisteddfods were held in north Wales. These were sponsored by successful London Welsh businessmen and their society, Y Gwyneddigion. Prizes, medals and catering were provided, attractive enough to draw bards and harpists from a wide area. For a time the Gwyneddigion Eisteddfod became an annual event starting in Corwen in 1789 and travelling to Llanelwy, Llanrwst and Denbigh. Although the London Welsh generosity eventually ran out, a renaissance had been sparked in Welsh poetry and music. A great many regional Eisteddfods of size and significance were staged throughout Wales, often relying on the financial support of the local gentry. |

| Tyfodd yr Eisteddfod a ddaeth yn wir boblogaidd, ond parhaodd yn ddim mwy na ymryson y beirdd a chystadlaethau i gerddorion. Nid tan 1819 yng Ngwesty’r Ivy Bush, Caerfyrddin, fe unodd Yr Eisteddfod â’r Orsedd a dechreuodd y draddodiad o seremonïau barddol sydd bellach yn ganolog i fywyd yr Eisteddfod Genedlaethol. | The Eisteddfod grew in popularity but remained nothing more than a bardic and musical competition. It was not until 1819 at the Ivy Bush Hotel, Carmarthen, that the Eisteddfod became united with the Gorsedd and there began the tradition of bardic ceremonies which are now central to the life of the National Eisteddfod. |

| Er yr ydym nawr yn meddwl fod yr Eisteddfod a Gorsedd y Beirdd fel undod annatod, dechreuwyd yr Orsedd gan Iolo Morganwg fel sefydliad annibynnol. Cymhleth ond diddorol tu hwnt yw astudio ei gymhelliant am wneud a’r trywydd a arweiniwyd at ei greadigaeth ddychmygol. Disgrifiodd yr Orsedd gan Y Parchedig John Walters, tiwtor Iolo ar y pryd, fel ‘a made dish’ gyda amrywiaeth o gynhwysion. | Although now we tend to think of the Eisteddfod and the Gorsedd of Bards as inseparably linked, Iolo Morganwg founded the Gorsedd as an independent institution. His motivations for doing so and the processes that led to his ‘imaginative creation’ are complex but extremely interesting. It was, as his mentor Rev John Walters remarked at the time, ‘a made dish’ with a variety of ingredients. |

| Heb drefn arbennig daeth chwant i adeiladu ar ei ymchwil ddilys i greu hanes rhamantaidd a delfrydol i Gymru o’r amserau cynharach. Canolog i weledigaeth Orseddol Iolo oedd pwrpas moesol o’r radd uchaf, a ffyddlondeb i air y Bod Mawr. Ceidwadwyr doethineb etifeddol oedd Beirdd yr Orsedd i fod. Nod Iolo hefyd oedd adfywio’r syniad o undeb y beirdd a oedd a’r cyfrifoldeb am gadw neu adolygu rheolau barddas, ac, yn null Eisteddfod Caerwys 1568, penderfynu, thrwy arholi, pwy oedd yn deilwng o’r teitl Pencerdd neu Brifardd. | In no particular order came his desire to build on his genuine research to create a romantic idealised history of Wales reaching back to earliest times. Central to Iolo’s concept of the Gorsedd was high moral purpose and adherence to the word of God. The Bards were to be keepers of inherited wisdom. Iolo’s aim was also to revive the idea of a ‘Guild of Bards’, who were to maintain and review the rules of poetry and, in the manner of the Caerwys Eisteddfod of 1568, decide through examination who was worthy of the title Pencerdd (Chief Poet) or Prifardd (Chief Bard). |

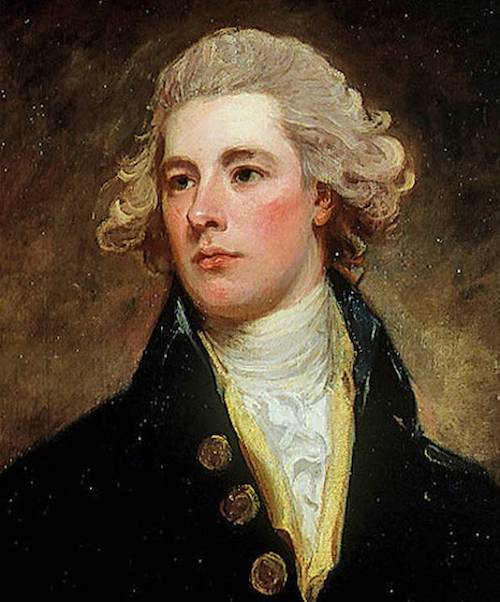

| Y cynhwysyn cryfach oedd cred angerddol wleidyddol Iolo. Yn ystod ei amser yn Llundain yn y 1790au cwrddodd â ffigurau pwysig yr oleuedigaeth: Tom Paine, Joseph Johnson, Samuel Coleridge a llawer mwy. Yn sgîl y chwyldro Ffrengig roedd Llundain yn grochan o syniadau newydd ac athroniaeth radicalaidd. Roedd Iolo yn ymdrybaeddu yn ‘the unparalleled eventfulness of this age.’ Ysgrifennodd bamffledi wrth-frenhinol gyda’r bwriad o danseilio Siôr III a llywodraeth ormesol William Pitt. Gêm beryglus oedd hon a chafodd nifer eu carcharu neu drawsgludo i Botany Bay am weithgareddau llai terfysglyd ond fe roedd eu gweithgareddau wedi cynhyrfu llywodraeth paranoid. Arestiwyd Iolo ei hun a chafodd ei arholi gan bwyllgor y Cyfrin Gyngor o dan lywyddiaeth y Prif Weinidog. | The most potent ingredient was Iolo’s passionate political belief. His time spent in London in the 1790 brought him into direct contact with major figures of the Enlightenment: Tom Paine, Joseph Johnson, Samuel Coleridge and many others. In the aftermath of the French Revolution, London was a cauldron of ideas and radical thought. Iolo revelled in ‘the unparalleled eventfulness of this age.’ He wrote anti-royalist pamphlets aimed at undermining George III and the anti-libertarian government of William Pitt. This was a dangerous game and a number of people found themselves imprisoned or transported to Tasmania for acts less rebellious than his but still judged provocative by a paranoid government. Iolo himself was arrested and questioned by a committee of the Privy Council chaired by the Prime Minister. |

Pitt the Younger |  |

| Mae’n arwyddocaol mae ar Fryn Y Briallu, Llundain ym 1792 cafodd yr Orsedd gyntaf ei chynnal yng nghanol y corwynt gwleidyddol. Dathlodd Iolo werthoedd y Chwyldro Ffrengig : cydraddoldeb, brawdoliaeth ryngwladol, hawliau dynol, gweriniaeth, gwrth-gaethwasiaeth a heddychiaeth. Gweithredodd Iolo yn gyhoeddus ond dan glog defodau derwyddol a barddoniaeth mesur caeth oedd yn ddigon i ddrysu’r ysbiwyr, o leiaf am sbel. Yn y pen draw sylweddolodd yr awdurdodau wir agenda Iolo a gwaharddwyd defodau’r Orsedd tan ddiwedd y rhyfel yn erbyn Ffrainc. | It is significant that Iolo’s first Gorsedd ceremony was held in English on Primrose Hill, London in 1792 in the centre of that political whirlwind. He celebrated the values of the French Revolution: equality, international brotherhood, human rights, republicanism, abolition of slavery and the cause of peace. He did this publicly but under the cloak of druidic ritual and strict meter verse, which was enough to confuse Pitt’s spies and informers, at least for a time. The authorities eventually recognised Iolo’s true agenda and the rituals of the Gorsedd were banned until the end of the war with France. |

| Roedd sawl gwahaniaeth i’r seremoni a welir heddiw. Llawer symlach oedd yr hen seremoni heb y mentyll coeth. Ni ymddangosodd y rheini am ganrif i ddod. Doedd dim meini hirion ond cylch o gerrig mân. Doedd dim Dawns y Flodau na’r Faner Gorymdaith. Nawr, fe gewch fynediad i’r Orsedd trwy enwebiad, ond roedd Gorsedd Iolo yn agor i unrhyw un oedd yn fodlon datgan ei foddlonrwydd i’w gwerthoedd. Roedd tri gradd o dderwyddon fel heddiw, ac fe oedd arholiad yn angenrheidiol i gyrraedd y graddau glas a gwyn. Gwyn oedd lliw y beirdd cymwysedig. Yn y r Orsedd gyntaf ym 1792 gallai hyd yn oed plentyn gael ei urddo i’r radd werdd; y dysgwyr neu Ovates. Fel heddiw roedd gan Y Cleddyf Mawr ran bwysig yn y ddefod. Cafodd ei weinio i ddangos swyddogaeth yr Orsedd i sefyll yn erbyn trais brenhinoedd a thywysogion. | There were several differences from the ceremony you see today. The old ceremony was much simpler, with no flowing robes. These did not appear until nearly a century later. There were no standing stones, only a circle of pebbles. There was no flower dance or processional banner. Admission to the Gorsedd is now by nomination, but Iolo’s Gorsedd was open to any willing to embrace its ideals. There were three orders of bards as today, but examination was only required for the blue and white orders with the white representing the guild of Bards itself. At that first Gorsedd in 1792 even a child could be and was admitted to the green order of Learners or Ovates. As today, the Great Sword was a vital part of the ceremony, sheathed to represent the role of the Gorsedd in standing against the violence of Kings and Princes. |

| Nid yw elfennau hanfodol y seremoni heb newid llawer ond mae’n gwestiwn agored os yw’r gynulleidfa yn y Pafiliwn heddiw yn sylweddoli pan maen nhw’n ymateb dair gwaith Heddwch i gwestiwn yr Archdderwydd A Oes Heddwch? maen nhw’n cymryd rhan mewn dathliad brawdoliaeth ryngwladol a heddychiaeth. Llwyddodd Iolo i osod dathliad o athroniaeth radicalaidd at galon ein cenedl. | The essential elements of the ceremony have not changed although it is uncertain if the audience in the Eisteddfod pavilion today realise that when they thrice reply Heddwch to the Archdruid’s question, A Oes Heddwch? they are taking part in a celebration of pacifism and international brotherhood. Iolo succeeded in placing this celebration of radical thought at the heart of the Welsh nation. |

| Wedi unoliaeth yr Eisteddfod â’r Orsedd ym 1819 roedd dylanwad cryf ychwanegol gan y corff newydd. Yn wahanol i’r Eisteddfod roedd athroniaeth yr Orsedd yn cofleidio pob agwedd o wybodaeth: celf, diwinyddiaeth, hynafiaeth, gwyddoniaeth, gwyddor naturiol, amaethyddiaeth, yn ogystal â llenyddiaeth a cherddoriaeth. O ganlyniad daeth yr Eisteddfod flynyddol yn sefydliad cenedlaethol cyntaf Cymru. Yng Nghysgod y Cryman gan Islwyn Ffowc Ellis mae’r prif gymeriad Harry Vaughan yn disgrifio’r Eisteddfod fel ‘y Brifddinas Cymru’. Roedd y cynulliad wythnosol o weinidogion, athrawon, gwleidyddion a ffermwyr o bob parth o Gymry wedi dod yn ferw deallusol blynyddol ble oedd trafodaeth syniadau newydd a mentrau newydd yn cael eu lansio. Ar sail y sefydliad cenedlaethol cyntaf adeiladwyd eraill; Y Llyfrgell Genedlaethol, y Prifysgolion and llawer llawer mwy i hyrwyddo sefydliadau diwylliannol, mudiadau radicalaidd, a’r drefn lywodraethol yng Nghymru. | The uniting of the Eisteddfod with the Gorsedd in 1819 gave the combined body powerful additional influence. Unlike the Eisteddfod, the philosophy of the Gorsedd embraced all aspects of knowledge; art, theology, antiquarianism, science, natural history, agriculture as well as literature and music. This made the annual Eisteddfod the first genuine national institution of Wales. In Cysgod y Cryman written in the 1940s, Islwyn Ffowc Ellis has his hero Harry Vaughan describe the Eisteddfod as ‘the Capital City of Wales’. This weeklong gathering of ministers, teachers, politicians and farmers from all parts of the Country became an annual intellectual fermentation where ideas were debated and new initiatives launched. This first national institution formed the foundation on which many others were built; the National Library, the Universities and many others concerned with the cultural institutions, radical movements and the governance of Wales. |

| Wrth gwrs, ar ddechrau’r 20fed ganrif pan gafodd diffyg tystiolaeth ffeithiol (dw i’n gwrthod y gair ffugiadau) cafodd creadigaethau rhamantaidd Iolo eu dadorchuddio ac fe roedd mawr ddicter - yn enwedig ymysg yr academyddion a fu’n darlithio ar sail y cred bod papurau Iolo yn wir hanesyddol. Taranodd y dylanwadol Syr John Morris-Jones yn erbyn seremonïau’r Orsedd. ‘Wrth gynnal arddangosfa fwy neu lai digrif - nid yw’r beirdd ond yn eu hiselhau eu hunain. Rhodder y gorau i’r chware ffôl hwn, a’r ymffrostio mawr a’r bloeddio.’ | Of course, when Iolo’s flights of romantic fancy were revealed in the early years of the 20th century as lacking factual foundation (I reject the term forgeries) there was great anger - particularly amongst the academics who had been delivering learned lectures based on the assumption that Iolo’s writings were historically true. The influential Sir John Morris-Jones raged against the Gorsedd ceremonies. ‘By continuing with this more or less laughable display the bards are only demeaning themselves. Let there be an end to this foolish play-acting, to this great boasting and proclaiming.’ |

| Ond roedd ymateb y cyhoedd yn dra gwahanol. Roedd W. Llewelyn Williams yn rhoi llais i’r farn boblogaidd yn Eisteddfod Caernarfon, 1921, ‘Dywedaf yn groew fod Cymru mewn perygl o golli rhai o’i phethau gorau drwy’r ysgolorion newydd. Mae enaid Cymro yn ei gân, ei hysbryd yn ei galon, ei hathrylith a’i hawen ar ei dafod. Dyna wreiddyn y mater; a neges yr Eisteddfod heddiw i’r ysgolorion ddylai fod- Na ddiffoddwch yr ysbryd’. | But the reaction of the public was quite different. W. Llewelyn Williams voiced the popular response in the Caernarfon Eisteddfod in 1921, ‘Let me say plainly that Wales is in danger of losing some of its finest institutions because of these new academics. The soul of Wales is in its song, its spirit in its heart, its genius and inspiration is on its tongue. This is the root of the matter; the message of the Eisteddfod to the academics should be- Do not extinguish the spirit.’ |

| Mae’r Orsedd yn dal yn hynod o boblogaidd hyd yn oed heddiw heblaw rhai amheuon parhaol dros ei genedigaeth. Dros y ddwy flynedd ddiweddaf rwyf i wedi ciwio am y coroni a’r cadeirio ond i gael fy nhroi i ffwrdd pan oedd y Pafiliwn dan ei sang neu yn orlawn. Y gwir yw- mae’n gweithio. Am dros ddwy ganrif mae’r Orsedd wedi bod yr ysbryd, yr athrylith a’r ysbrydoliaeth at galon beth bynnag mae Cymru olygu i ni. Hir oes i’r Orsedd. | The Gorsedd remains hugely popular today despite lingering concerns about its origins. For the last two years I have joined the queue for both the crowning and the chairing only to be turned away when the pavilion was packed to the point of overflowing. The truth is- it works. For over 200 years the Gorsedd has been the visible spirit, genius and inspiration at the heart of whatever Wales means to us. Long may it continue. |

| Diolch Iolo. | Thank you Iolo. |

Nid yw elfennau hanfodol y seremoni heb newid llawer ond mae’n gwestiwn agored os yw’r holl gynulleidfa yn y Pafiliwn heddiw yn sylweddoli pan maen nhw’n ymateb dair gwaith Heddwch i gwestiwn yr Archdderwydd A Oes Heddwch? maen nhw’n cymryd rhan mewn dathliad brawdoliaeth ryngwladol a heddychiaeth.

Darlun o Pryn Briallu, Llundain / Illustration of Primrose Hill, London

Darlun o Pryn Briallu, Llundain / Illustration of Primrose Hill, London

Awdur Myfi, Iolo yw Gareth Thomas. Dyma lyfr sy'n ailadrodd yn y person cyntaf hanes Iolo Morganwg- o'i febyd i Orsedd Glynogwr ym 1798. Amlweddog yn wir oedd Iolo Morganwg: fe fu'n saer maen, ysgolhaig hunanddysgedig, bardd, emynwr, gwleidydd, gwladgarwr, chwyldröwr, derwydd, busneswr aflwyddiannus, caeth i gyffuriau, ymgyrchwr dros hawliau dynol, ac ar ben hynny oll, fe oedd y dyn a gyflawnodd y ffugiad llenyddol mwyaf yn hanes Ewrop.

Awdur Myfi, Iolo yw Gareth Thomas. Dyma lyfr sy'n ailadrodd yn y person cyntaf hanes Iolo Morganwg- o'i febyd i Orsedd Glynogwr ym 1798. Amlweddog yn wir oedd Iolo Morganwg: fe fu'n saer maen, ysgolhaig hunanddysgedig, bardd, emynwr, gwleidydd, gwladgarwr, chwyldröwr, derwydd, busneswr aflwyddiannus, caeth i gyffuriau, ymgyrchwr dros hawliau dynol, ac ar ben hynny oll, fe oedd y dyn a gyflawnodd y ffugiad llenyddol mwyaf yn hanes Ewrop.

Gareth Thomas is the author of I, Iolo, a first-person retelling of the story of Iolo Morganwg- from his boyhood to the Glynogwr Gorsedd of 1798. Iolo Morganwg had many faces: stonemason, self-taught scholar, poet, hymnist, politician, patriot, revolutionary, druid, failed businessman, drug addict, campaigner for human rights and perpetrator of the greatest act of literary forgery in European history.

Mae'r llyfr Myfi, Iolo (fersiwn Cymraeg) ar gael o Y Lolfa: | I, Iolo (English version) is available from Y Lolfa: |