David Jandrell's mission in life is documenting the the dialect of the South Wales Valleys (also known as Wenglish), and sharing his love of phrases such 'Tidy', 'Butt', 'Now in a minute' and 'Cwtch' with the wider world. Here he introduces Valleys English, gives a sample of popular phrases and explanations from Welsh Valleys Phrasebook and then recounts his story of developing an interest in documenting this dialect...

Skip to: Sample Glossary / My life through Valleys English

Welsh Valleys Humour / Wenglish Dialect / Talk Tidy

A first visitor to Wales will almost certainly have to converse with a local at some stage, and that is where the trouble may start. Ask for directions and you will be no better off than if you’d bought a sat nav and the ‘speaker’ gave all directions in Klingon.

A first visitor to Wales will almost certainly have to converse with a local at some stage, and that is where the trouble may start. Ask for directions and you will be no better off than if you’d bought a sat nav and the ‘speaker’ gave all directions in Klingon.

You will have very little idea of what has been said to you. You’ll probably assume that the person you spoke to answered you in Welsh. The reality is that that person would have actually been speaking to you in English – and it is this version of English that this piece of work is all about – that being, non-standard English as used in Wales in everyday conversation.

This language is far removed from English that you will be used to and hopefully these pages will ease your communication problems during your stay in the country. Although, at first glance, you may wonder what language it is written in – it is actually written in English. The phonetic version of the written language, that is.

Pronunciation is the biggest hurdle to overcome and the Welsh Valleys Phrasebook is prepared with this in mind. The thing to remember here is that our non-standard words are not necessarily pronounced the Welsh way, even though those words may look like Welsh on paper!

So, if you see an English word, say it as that word is pronounced in English. That will be how it is pronounced in Wales – the difference being that word will mean something else.

Sample Dialogue and Glossary

Press the play button above to listen to David narrate a typical Valleys dialogue, and then match it to items you can read below!

Items in italics relate to a definition that can be found in the full book, which contains over 120 more phrases. Following the definition is a sample dialogue.

Big massive: Huge

“We were down the club earlier and this couple came in and you should’ve seen ‘em. She was a big massive bomper and he was a tiny little dwt.”

Boggin': Unattractive, ugly, unappealing,etc. Similarly, regional variations: Bulin’, Gompin’, Mingin’ Mulin’, Muntin’ & Scruntin’

“Have you seen the state of Ron’s new girlfriend? Boggin’ mun.”

“I yeared she was bulin’. That bad is she?”

“Oh aye, gompin’.”

“His last girlfriend was no oil paintin’ mind.”

“More like an oil slick, mingin’ she was.”

“Oh aye, mulin mun.”

“Mind you, he’s muntin’, can’t expect ‘im to pull any lookers to be honest.”

“Aye, to be fair all his girlfriends ‘ave bin scruntin’.”

Butt/Butt/Butty: Informal term of affection to a mate, pal, friend, associate. The Welsh version of the English, ‘bud’ or buddy’.

“Where to are you off to butt?”

“Alright butt? I’m off to meet Bob down the park.”

“Hang on butt, here’s a stroke of luck, here he comes. Alright butt, how’s it going?”

“Aye, I’m alright butt. What about you?”

“Alright butt, aye.”

“Tidy.”

Cwtch: A very common word, now understood by most English speakers. Made even more famous when international rugby referee Nigel Owens belittled brawling players on national TV when he said: “If you want a cwtch, do it off the field, not on it”. Commonly, cwtch has three meanings:

A cuddle: Physical show of affection.

To hide something: Example: “I was wrapping his birthday present and he walked in. I had to cwtch it a bit quick under the cushion.”

A place where you put things; akin to the English ‘cubby hole’.

“Cwtch it in the cwtch then give us a cwtch.”

Dai Twice: Contrived name allocated to anyone who’s real name is David Davies.

Dooberry: Generic name for something or someone used when the speaker either doesn’t know the name of the subject or can’t be bothered to use it. Similarly: Do-ins, Doodah, Mackonky, Oojackapivvy, Shmongah, Usser, Whatyoumcallit, Woducall, Wossnim etc.

“Have you seen the dooberry?”

“It’s over there by the oojackapivvy.”

“Who put it there?”

“Wossnim, before he went into town.”

“Wossee gone to town for?”

“Gone to pick up a doodah.”

“I wish he’d said, I wanted a mackonky to go with this shmongah.”

“I think I’ve got one of them, over there by the whatyoumacallit. See it?”

“Aye, great stuff. I thought for a moment I’d have to borrow one off Woducall.”

“He ‘asn’t got one, he uses a different Do-ins.”

Drive: Generic name for the driver of a public service vehicle. Commonly heard when the contents of a double-decker exits at the bus station:

“Cheers Drive.”

“Cheers Drive.”

“Cheers Drive.”

“Cheers Drive.”

“Cheers Drive.”

“Thank you Driver.” (Middle class passenger)

Gutsy: Greedy or gluttonous.

“Where’s all them doughnuts to?”

“I ate ‘em.”

“You gutsy bastard!”

Now, in a minute: Some time later. Certainly not soon.

“Willew turn that football off? I want to watch the drama on ITV.”

“I’ll turn it off now in a minute love, when it finishes.”

“How long is left?”

“They’re three minutes into the first half.”

Tidy: A real monster. Tidy can mean just about anything positive, pleasurable, good, neat, smart, satisfying, etc., that the user chooses to describe as ‘tidy’. The list of possible definitions is inexhaustible, but could be represented in the abridged example:

“How’s it going butt?”

“Tidy, mun aye.”

“How did the interview go?”

“Tidy butt, I got the job. They gimme a maths test and I done it tidy by all account.”

“Tidy! Much different to what you’ve bin doin’”

“Oh aye, tidy job this is. Didn’t like my last job much to be honest. Gotta dress tidy an’all.”

“Tidy. Office job is it?”

“Aye. Gotta get some tidy shoes before I start. I’ve got a tidy suit and tidy shirts, but my shoes ‘en up to much.”

“Well you gotta ‘ave tidy shoes if you d’work in an office butt. Create a tidy impression see.”

“Well, I gotta dash. I gotta tidy my room before I get into town for them shoes.”

“All the best butt. See you in a bit I spoze. I’ll tell my missus about your new job.”

“Tidy. See you butt.”

Traaaaa: Goodbye. Farewell, ta-ta

“Ok, traaaa, see you Sunday.”

“Aye, see you Sunday, traaaa.”

“Traaaa.”

“Traaaa.”

Yer: Very versatile interchangeable word for; ear, year, here, hear. At the hospital:

“What’re you doin’ yer?” (here)

“Got summut wrong with my yer.” (ear)

“What? You mean you can’t yer things?” (hear)

“Aye, ‘ad the problem over a yer and only now they’ve got round to seeing me.” (year)

Up by yer

If you ask a Welsh person where they are, or where something is, where they’ve been, where they’re going, you may not be fully au fait with the answer you get. We tend to like to instill a bit of mystery into the whereabouts of the subject of the question by not pinpointing its exact location, but steer you towards somewhere nearby. A form of guessing game that is played and enjoyed by all- the habit of saying, “By here” or “By there”.

So, if you ask where the Radio Times is and the response is “By there”, you may well be in the same boat as you were before you asked the question. This will mean that the responder will be making some gesture, either with his/her eyes or pointing with a finger which means that you must make a conscious effort to observe him/her when he/she responds so that you can follow the physical signs to find what you are looking for.

On the other hand, the responder may be more specific and reply with a: “By there by the coffee table.” This will enhance your success at finding the Radio Times exponentially because all you have to do is find the coffee table and hunt around in that vicinity.

The ‘by’ in this case is actually a non-descript unit of measurement. The Radio Times could actually be on the coffee table, on the floor at the side of the coffee table, a yard away from the coffee table or roughly within the same postcode that the coffee table is sitting in at the time. Quite a lot of scope there, but all perfectly acceptable.

You will see that I did not exaggerate when I made reference to within the same postcode when I tell you about a snippet gleaned from a conversation I heard a few years ago:

“Where to is Manchester?”

“It’s up north somewhere, up by Liverpool.”

In this case, the ‘by’ represented a distance in the region of 34 miles! As you can see, in this case it has actually exceeded the post-code boundary.

Asking and replying using the ‘by’ method

There are no standard protocols when questioning and answering here. There are certainly no rules covering tense, grammar, syntax – this is entirely governed by the speaker, and depending on the speaker, this can become as convoluted as he/she deems appropriate. Here are some examples of questions/answers which show the scope for the progression of bizarreness.

Questions Answers

“Where to is it? “It’s up by yer.”

“Where is it to?” “It’s down under by there.”

“Where’s it by?” “It’s over by there.”

“Where to is it by?” “I don’t know where to it’s by”

“Where by is it to?” “It’s up over by yer.”

“Where by will you be to.” “In the bus station, by Burger King.”

“I put it by yer, and it en by yer now.” “It was by yer. Where’s it’s to now?”

David Jandrell: My life through Valleys English

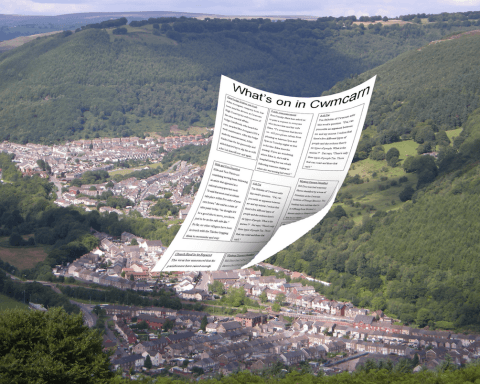

My immersion into the non-standard version of English spoken in the Welsh valleys began in 1955 when my mother gave birth to me on the kitchen table in a tiny house on the border of two villages, Cwmcarn and Pontywaun, in the county then known as Monmouthshire. Although I can’t remember it, the first words that I would have heard would have been along the lines of:

My immersion into the non-standard version of English spoken in the Welsh valleys began in 1955 when my mother gave birth to me on the kitchen table in a tiny house on the border of two villages, Cwmcarn and Pontywaun, in the county then known as Monmouthshire. Although I can’t remember it, the first words that I would have heard would have been along the lines of:

“Cor, flippin ‘eck mun. Inny luvly.”

“Aw bless. Jess like ‘is daar.”

“Worra luvly little dwt, he is, inny. Oooooh aye.”

“Worrew gonna call ‘im Joan?"

“Come over by yer Margaret and see your brother. Go on mun, give ‘im a kiss innit.”

And that was the language I grew up with.

In those days, Monmouthshire was a political hot potato, with regular debates of: is Monmouthshire in England or in Wales? This debate had been going on and off for over 400 years and even now in 2018 it is not clear when this area was ‘English’ or ‘Welsh’ or how long these periods of Englishness and Welshness lasted to classify those who lived there.

When I was in Cwmcarn Junior School the education authority seemed to lean towards Englishness, as I remember from my introduction to the National Anthem. It would have been sometime before St. David’s Day when the whole school were ushered into the school hall and told to sit cross-legged on the floor. The Headmaster unrolled a large printed canvas with ‘Land of Our Fathers’ in huge letters written on it. The anthem was actually written in English, and that’s how we were taught the anthem – in English. For some reason, the educationalists throughout my primary secondary and tertiary education never deemed it compulsory to teach us the Welsh version.

My first ever contact with the Welsh language proper came about during visits to Cwmcarn post office. The postmistress, Mrs Clarke, rarely tended the counter- instead she sat at the back of the shop and shouted in Welsh at someone into one of only seven telephones that were in Cwmcarn at the time. Mrs Clarke often came up in our conversations in school:

“Dwn Mrs Clarke talk funny?”

“Aye. Can’t understand ‘er mun.”

“Our mam d’reckon it’s Welsh she’s talking.”

“Cor, flippin’ ‘eck, Welsh is it?”

“Aye, according to our mam anyhow.”

“Avew gorra shout Welsh?”

“Speckt so, Mrs Clarke’s always shouting when she d’talk it.”

So apart from Mrs Clarke, the language that I was immersed in was the south east Welsh Valleys version of English.

In 1974 the county on Monmouthshire disappeared and replaced by the county of Gwent and we were now all officially Welsh. Phew! Having said that, Gwent was very Anglicised at the time compared with most of its surrounding areas, and still is.

My mother’s language was intermittently anglicised. This phenomenon occurred when she was on the telephone. My parents were very friendly with Charles Dickens’ great-grandson, Cedric Dickens, and he telephoned them regularly. He spoke with a very refined public school English accent (think Jacob Rees-Mogg), so when the phone rang Mother would get into ‘the zone’ to be ready just in case the caller was Cedric. If it wasn’t, she still maintained the posher stance but toned it down a bit so that she didn’t appear snobbish to whoever she was talking to. If it was Cedric though, she went for the ‘full monty’.

When I got to the fifth form in school (aged 15) I noticed that the girls, with whom we’d shared every lesson since we entered secondary education, started to become a ‘bit posher’ and began to refine their language as they tried to sound sophisticated. Us boys didn’t really embrace this and distanced ourselves from them, as we were only interested in fighting and playing football. We didn’t need to use BBC English in order to follow these pursuits!

Before leaving for University, my group of friends decided that we would all meet up in the Beaufort pub in Newbridge over the following Christmas break to compare notes on our first term away from home. I noticed some drastic changes in the language that me ex-peers were using- I was the only person using the language that we all spoke the previous September. Instead of picking up regional English accents, they all had the same accent- a version, or as near as they could get, to ‘BBC English’ obviously to ‘fit in’ with their newly acquired peer groups

I didn’t feel as if I ‘knew’ them any more and was quite disappointed that these people had modified their speech and, ‘bettered themselves’ in their eyes. Even the swearing had been poshed up. I noticed that the standard valley exclamation, ‘fuckin’ ‘ell mun!’ had morphed into the more refined sounding, “Fahking Hell!”

I heard the term, ‘well spoken’ a lot in those days and those who were ‘well spoken’ deserved more respect and a better level of customer service from shopkeepers if they were ‘well spoken’. I began to hear this term more and more and my sister extended it to being ‘better spoken'. To me, ‘well spoken’ was code for ‘not using the Valleys language or accent.’

I always made sure I maintained my valleys accent throughout my 20s and 30s while living in England. When I visited shops I always asked for what I wanted in my natural Valleys accent. This meant that, mostly, I would not be understood and my request would be met with a, ‘pardon?’

When returning to work in Wales in my 40s I noticed that the bonding of different social groups centred entirely around the friendly but competitive banter about how we all spoke. One thing this new environment taught me was that, despite the very diverse mix of accents- from the west country to Swansea, including Cardiff, Barry, Newport and the Valleys, the consensus was that the least desirable accent to have was, yes, you guessed, the Valleys accent.

Interestingly, my Valleys accent has been ridiculed and patronised more by people from Newport and Cardiff than any other regions in the UK – including the times when I resided ‘over the bridge’. Yes, if you had a Valleys accent you were the pits. It was probably because of this that I started to take an interest in accents, idioms and language which led me to observe and report on them in the future.

I had observed how diverse the Valleys accent was in the Ebbw Valley (where I now live) and had identified vast differences in accents (five distinct) between Risca in the south to Ebbw Vale, in the north. Risca is very anglicised, but travel north towards places like Abertillery, Brynmawr, Ebbw Vale, their vowel sounds get flatter and more drawn out, changes in syntax are marked and aitches rarely sounded. So, I was well armed with thoughts of noticeable changes in ways of speaking between distances of five or six miles in the Ebbw valley, but I was not prepared for what I was about to experience when I took up a teaching post at Ystrad Mynach college in 2000.

Students at Ystrad Mynach came from the Rhymney, Rhondda, Cynon and Taff valleys. By this time you’d think I was a bit of an expert in Valley accents, dialect and idioms. Not so. It took me a good eighteen months before I was fully au fait with the language used by the students. In my early days I failed to understand many of the students because their version of the Valleys English was so far removed from the version that I used. They didn’t have any trouble understanding me though – according to them, I spoke with a refined English accent, akin to newscasters on the telly.

Even the staff regarded me as a bit posh, even aloof. I remember a brief conversation with a colleague not long after I’d started:

“Where to are you from then, butt?”

“Cwmcarn.”

“Where by is that to?”

“Near Newport.”

“English arrew?”

“Er …. no. Welsh.”

“Bugger off, Newport’s England mun.”

They believed this so strongly that amongst a small group of colleagues, I was known as, 'English Dai.'

When I wrote Welsh Valleys Phrasebook I drew on the non-standard English used in a wide spectrum of different areas gleaned from my own ability to speak fluent Ebbw valleyspeak and my recently acquired Rhymney/Rhondda/Cynon/Taff valleyspeak. Whilst very diverse, the nonstandard English used was standard within the villages that used it and was the norm – even though 10 miles away, the language could be very different. I concluded that the language is as vibrant and colourful as it has always been.

Will the language of the Welsh valleys ever die out? I hope not.