Across Wales, each Welsh-speaking communitity, whether it’s a town or a valley, uses its own words and phrases to create new meanings that not to be heard anywhere else. Here Dafydd Gwylon, a native of Pontarddulais, shares his favourite examples of his region’s dialect.

| Mae’n ddiddorol clywed a sylwi ar eiriau tafodiaith Cymru. Os ych chi’n blentyn ifanc neu yn ceisio deall beth mae rhywun yn ddweud a’r geiriau yn newydd i chi mae’n brofiad gwahanol iawn! Cȇs i fy magu nepell o Abertawe ym Mhontarddulais {y Bont} ac roedd fy rhieni yn siarad Cymraeg Ceredigion. Roedd fy rhieni wedi eu magu nepell o Aberystwyth. | It is interesting to hear and take notice of Welsh dialect words. If you are a young child or are trying to understand what someone is saying and the words are new to you it is a very different experience! I was brought up not far from Swansea in Pontarddulais (y Bont) and my parents spoke Cardiganshire Welsh. My parents had been brought up not far from Aberystwyth. |

| Roedd cynifer o eiriau gwahanol gan bobol y Bont fel ‘taclu’ am wisgo, ‘carco’ am ofalu, ‘tyle’ am rhiw, ‘dishgwl’ am edrych, ‘can’ am flawd, ‘colfen’ am goeden, ‘llyched a thyrfe’ am fellt a tharanau a ‘siwrnai’ am unwaith. Yng Ngheredigion a nes i’r gogledd mae ‘siwrnai’ yn golygu taith. | The people of y Bont had a number of different words, such as 'taclu for 'wisgo' (to dress), 'carco' for 'gofalu' (to care, mind), 'tyle' for 'rhiw' (hill), 'can' for 'blawd' (flour), 'colfen' for 'coeden' (tree), 'llyched a thyrfe' for 'mellt a tharannau' (thunder and lightning) and 'siwrnai' for 'unwaith' (once). In Cardiganshire and further north 'siwrnai' means 'taith' (journey). |

| Byddai fy Mamgu a’m Modryb ger Aberystwyth yn dweud wrtha’i yn blentyn gymaint o’n i wedi ‘prifio’ –eu gair nhw am ‘tyfu’. ‘Lodes’ oedd eu gair nhw am ferch ifanc ac os oedd anifail neu greadur wedi marw roedden’hw’n dweud ei fod wedi ‘trigo’. Pan oedd eisiau bwyd ofnadwy y disgrifiad oedd ein bod yn ‘clemio’. Disgrifien nhw ambell i ferch yn ‘haden’ os oedd hi’n blentyn/person bywiog llawn ysbryd. | My grandmother and aunt from Aberystwyth way would tell me as a child how much I had grown using their word 'prifo' rather than 'tyfu'. Their word for a young girl was 'lodes' and if an animal or some creature had died they would say it had 'trigo' (to perish, die, especially of animals; trigo more commonly means to live, dwell). When someone was in great need of food they were said to 'clemio' (to be starving, cf. English dialect 'I'm fair clemmed'). They would describe some girl as a 'haden' (literally, a small seed) if she was a lively child/person full of spirit. |

| Yn ardal Pontarddulais ‘starfo’ oedd y gair am eisiau bwyd yn awgrymu efallai mwy o ddibynnu ar y Saesneg yno a pan oech chi’n oer iawn roech chi’n ‘sythu’. | In the Pontarddulais area the word for wanting food was 'starfo', perhaps suggesting more of a dependency on English there, and when you were cold you would 'sythu'. |

| Yn ardal y Bont hefyd roedd y Cymry yn ynganu nifer o eiriau ychydig yn wahanol megis ‘lluwch’ am ‘llwch’, ‘llidi’ am lludw, ‘cenol’ am canol, ‘lo’s’ am loes, ‘tishen’ am teisen ‘sgidshe’ am esgidiau. | In the Bont region the Welsh would also pronounce a number of words a little differently, like 'lluwch' for 'llwch' (dust), 'llidi' for 'lludw' (ash), 'cenol for 'canol' (centre), 'lo's' for loes (great pain), 'tishen' for 'teisen' (cake) and 'sgidshe' for 'esgidiau' (shoes). |

| Fe glywch ambell air o dafodiaith Pontarddulais wrth wrando ar Taro'r Post Radio Cymru pan mae Garry Owen yn cyflwyno’r rhaglen. Un o’r Bont yw Garry ac mae’n para i fyw yn yr ardal. | You can hear some Pontaddurlais dialect words if you listen to Radio Cymru's Taro'r Post when Garry Owen is presenting the program. Garry is a Bont man and still lives in the area. |

| Roedd dywediadau lliwgar cofiadwy gan fy Mam (o Geredigion) oddi mewn i waliau’r cartre! Roedd rhywun anniben yn edrych ‘fel bwbach’ a rhywun tenau iawn ‘fel sgadenyn’ neu ‘fel sgilet’. | My mother (from Cardiganshire) used some memorably colourful expressions within the walls of her own home! Someone untidy would look like a 'bwbach' (bogy, scarecrow) and someone very thin like a 'sgadenyn (= ysgadan, herring) or 'sgilet' (skillet, saucepan). |

| Roedd rhywun oedd yn holi llawer yn ‘holi perfedd’ ac os oedd rhywun heb ddangos llawer o ddeall a synnwyr cyffredin wedi ‘cael ei fagu dan badell’, ac ‘eisiau clymu ei phen’ am rywun yn gwneud rhywbeth ffȏl. Os oedd rhywun yn mynd yn dew neu yn bwyta gormod wel gwell ‘codi’r rhastal arno’. | Someone who asked too many question was 'holi perfedd' (literally, asking guts), and someone showing a lack of understanding or commonsense had 'been brought up in a kettle', while someone doing something foolish 'needed to get his head together'. If someone was getting fat or was eating too much 'better get a manger for them'. |

| Roedd fy Nhad wedi ei fagu yn ardal Trefenter, Mynydd Bach, Ceredigion ac roedd yntau a’i deulu a’u dywediadau diddorol. Roedd rhywun oedd yn gwastraffu amser yn ‘hela wowcs’. | My father had been brought up in the Trefenter, Mynydd Bach, Cardiganshire area and he and his family also had their interesting turns of phrase. Someone wasting time was 'hela wowcs' (= hela wewcs, pottering about). |

| Wrth sȏn am ddod a phethe i drefn fe ddywedai dod a phethe ‘i fwcwl’. Ambell waith wrth wneud ambell dasg roedd eisiau ‘panso’ sef cymryd pwyll a gofal. Roedd nhad hefyd wrth grymanu’r ardd a’r cae yn casglu ‘ffrwcs’ i’w llosgi. | Talking about tidying up he said he was putting things 'in a buckle'. Sometimes when carrying out some task there was a need to 'panso', that is to take pains or great care. My father would also mow the garden and field with a sickle collecting 'ffrwcs' (weeds, grass mowings) to burn. |

| Ymadrodd cyffredin gan fy rhieni oedd ‘cwiro’ a sȏn am ‘gwiro sanau’. Dȇs i ddeall mwy am y defnydd o’r gair wrth glywed Emyr Evans o ardal Felinfach, Llanbed, yn dweud ar S4C am ‘gwiro tractor’. Rwy’n meddwl bod e’n dod o’r gair ‘cywiro’. | A common expression with my parents was 'cwiro' (to mend) and they talked about 'cwiro sanau' (mending socks). I came to understand more about the use of the word when I heard Emyr Evans from the Felinfach, Llanbed area talking on S4C about 'gwiro tractor' (mending a tractor). I think that it comes from the word 'cywiro' (to correct, put right). |

| Ymadrodd cyffredin yn y capel adeg angladd oedd yn rhyfedd i glust plentyn oedd y cyhoeddiad ‘i wrywod yn unig’ . (Doedd y gair ‘gwrywod’ ddim yn air cyfarwydd i blentyn a phobl ifanc bryd hynny). | In chapel, on the occasion of a funeral, a common saying which was strange to the ear of a child was the proclamation 'i wrywod yn unig’ (to males only). (The word ' gwrywod' was not a familiar one to children and young people at that time). |

| Pan oedd fy mam yn heneiddio ron i’n sylwi mwy ar ei hymadroddion. Pan ofynwn iddi sut oedd hi yn teimlo fe atebai ‘Purion’ sy’n air tafodiaith Ceredigion am ‘go lew’. Roedd mam wedi treulio rhan helaeth o’i hoes ym Morgannwg a sir Gȃr! Gair arall a ddefnyddiai wrth gynnig darn o ffrwyth neu frechdan imi: ‘Hwde’ am ‘cymer’ o cymeryd fel math ar orchymyn. | As my mother got older I took more notice of her sayings. When I asked her how she was feeling she would answer 'Purion', which is Cardiganshire dialect for 'not too bad'. Mum had spent the greater part of her life in Glamorgan and Carmarthenshire. Another word she would use when offering me a piece of fruit or bread was 'Hwde', for 'cymer' from 'cymeryd' as a kind of command. |

| Rwy’n edrych mlaen at glywed sylwadau darllenwyr Parallel.Cymru am yr ymadroddion uchod: e.bost: dafydd.gwylon@btinternet.com. | I am looking forward to hearing the observations of Parallel.Cymru readers concerning the above expressions: email: dafydd.gwylon@btinternet.com. |

| Rwy’n disgrifio pobol a mwy am yr ardaloedd yma yn fy llyfr Mȇs Bach a Gwreiddiau ac mae nifer o luniau a ‘dogfennau’ hanesyddol yn y llyfr hefyd. | I describe the people and more about these areas in my book Mȇs Bach a Gwreiddiau ('Little Acorns and Roots', and there are also a number of illustrations and historical 'documents' in the book. |

gwales.com/bibliographic/?isbn=9781903529249

]]>

Bord Cynnwys / Table of Contents

- Colofn 5: Cymraeg llyfr a Chymraeg llafar / Book Welsh and Spoken Welsh: looking back to look forwards

- Colofn 4: Creu Geiriadur Cymraeg Gomer / Creating Geiriadur Cymraeg Gomer

- Colofn 3: Creu adnau gwybodaeth ddigidol ddwyieithog, gweiadur.com / Creating a bilingual digital knowledge repository, gweiadur.com

- Colofn 2: Creu Geiriadur Gomer i’r Ifanc

- Colofn 1: Trosolwg o fy llyfrau / Overview of my books

Colofn 5, Medi 2018

Cymraeg llyfr a Chymraeg llafar: edrych yn ôl er mwyn edrych ymlaen

Book Welsh and Spoken Welsh: looking back to look forwards

| Rwy’n edrych yma ar y gwahaniaeth rhwng y ffordd y mae’r Gymraeg yn cael ei siarad a’r ffordd y mae’n cael ei hysgrifennu. | Here I’m considering the difference between the way Welsh is spoken and the way it’s written. |

| Wrth drafod natur ‘gwirionedd’, casgliad dau o wyddonwyr mawr yr 20fed ganrif, Albert Einstein a Werner Heisienburg, oedd: ‘There are two kinds of truth. To the one kind belong statements so simple and clear that the opposite assertion obviously could not be defended. The other kind, the so-called “deep truths”, are statements in which the opposite also contains deep truth.’ | When discussing the nature of ‘truth’, the conclusion of two of the 20th century’s great scientists, Albert Einstein and Werner Heisenberg, was: ‘There are two kinds of truth. To the one kind belong statements so simple and clear that the opposite assertion obviously could not be defended. The other kind, the so-called “deep truths”, are statements in which the opposite also contains deep truth.’ |

| Un enghraifft o hyn, medden nhw, yw ‘the mutually exclusive relationship which will always exist between the practical use of any word and attempts at its strict definition’. | One example of this, they said, is ‘the mutually exclusive relationship which will always exist between the practical use of any word and attempts at its strict definition’. |

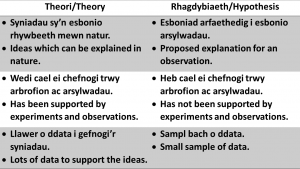

| Cymraeg llafar – y ffordd y mae iaith yn cael ei defnyddio’n ddyddiol gan siaradwyr yr iaith, a Chymraeg llyfr – yn dilyn rheolau gramadeg, geiriadur a Cherdd Dafod. | Spoken Welsh – the way the language is used daily by speakers of the language, and Book Welsh – following grammatical rules, a dictionary and Poetical Principles. |

| Cymraeg Llafar Erthygl ryfeddol arall yw The Mystery of Language Evolution gan rai o enwau mwyaf blaenllaw yr ymgais i ddarganfod strwythur sylfaenol iaith (fel ffordd o ddatblygu deallusrwydd artiffisial). Eu casgliad yw: ‘Based on the current state of evidence, we submit that the most fundamental questions about the origins and evolution of our linguistic capacity remain as mysterious as ever...with essentially no explanation of how and why our linguistic computations and representations evolved.’ | Spoken Welsh Another wonderful article is The Mystery of Language Evolution by some of the most prominent names in the attempt to discover the fundamental structure of language (as a way of developing artificial intelligence). Their conclusion is: ‘Based on the current state of evidence, we submit that the most fundamental questions about the origins and evolution of our linguistic capacity remain as mysterious as ever...with essentially no explanation of how and why our linguistic computations and representations evolved.’ |

| Mae iaith yn rhan o’r genom dynol ac yn cydymffurfio â threfn anochel esblygiad. | Language is part of the human genome and conforms with the inescapable course of evolution. |

| Cymraeg Llyfr Mae iaith llyfr yn wahanol. Nid yw darllen nac ysgrifennu iaith yn bethau naturiol sy’n perthyn i ni yn yr un ffordd ag y mae siarad iaith. Maen nhw’n sgiliau y mae’n rhaid i ni eu dysgu. | Book Welsh Book-based language is different. Neither reading nor writing a language are natural things that belong to us in the same way that speaking a language does. They’re skills that we have to learn. |

| Mae’r Gymraeg yn iaith sydd wedi cael ei hysgrifennu ers mil o flynyddoedd a rhagor. Dros y cyfnod maith hwn y mae patrymau a chonfensiynau wedi datblygu sy’n cael eu hadnabod erbyn hyn yn ‘Gymraeg safonol/Cymraeg cywir neu Gymraeg llenyddol’. Mae Cymraeg safonol yn fwy ceidwadol nag iaith lafar sy’n esblygu ac yn datblygu drwy’r amser, ond mae wedi ei adeiladu ar sail model syml yn hytrach nag ar y ffordd gymhleth y mae iaith lafar yn gweithio. | Welsh is a language that’s been written for a thousand years and more. Over this huge period patterns and conventions have developed which are known now as ‘Standard Welsh/Correct Welsh or Literary Welsh’. Standard Welsh is more conservative than spoken language which is evolving and developing all the time, but it’s been built on the basis of a simple model rather than on the complex way that spoken language works. |

| Y Gymraeg 600 - 1600 Dros fil a hanner o flynyddoedd yn ôl yr oedd yna urdd o wŷr proffesiynol (nid oedd gwragedd yn cael bod yn aelodau) yr oedd gramadeg y Gymraeg yn rhan hollbwysig o’r sgiliau yr oedden nhw’n gorfod eu meistroli. Yr oedd hyn yn golygu eu bod yn gorfod bwrw prentisiaeth a phrofi eu bod wedi meistroli’r sgiliau angenrheidiol i lefel uchel. Nid cyfreithwyr, na chyfieithwyr nac athrawon eglwysig oedd y rhain, ond beirdd. | Welsh 600 - 1600 Over 1,500 years ago there was a guild of professional men (women were not allowed to be members) for whom Welsh grammar was an all-important part of the skills they had to master. This meant that they had to undergo an apprenticeship and prove they had mastered they necessary skills to a high level. These were not lawyers, nor translators, nor ecclesiastical professors, but poets. |

| Mae lle i gredu bod y beirdd hynaf oll, y Cynfeirdd (o’r 6ed ganrif ymlaen, rhai fel Aneirin a Taliesin) oedd yn canu i frenhinoedd y cyfnod, yn dilyn traddodiad dysg y Derwyddon y mae Iŵl Cesar yn sôn amdano. Erbyn cyfnod Beirdd y Tywysogion (o’r 12fed ganrif ymlaen, rhai fel Gruffudd ap Cynan a Cynddelw Brydydd Mawr) yr oedd y beirdd proffesiynol hyn yn cael eu hyfforddi mewn ysgolion barddol lle’r oedd crefft ‘barddas’, oedd yn cynnwys gramadeg, yn cael ei dysgu. | There’s reason to believe that the earliest poets of all, the Cynfeirdd (from the 6th century onwards, people such as Aneirin and Taliesin) were performing for the kings of the period, following the traditional discipline of the Druids which Julius Caesar mentions. By the period of the Poets of the Princes (from the 12th century onwards, people like Gruffudd ap Cynan and Cynddelw Brydydd Mawr) these professional poets were being trained in bardic schools where the craft of ‘poetics’, which included grammar, was taught. |

| Nid gramadeg fel yr ydym ni yn ei adnabod oedd hwn ond enw ar un agwedd ar ddysg yr Oesoedd Canol. Mae Tri Chof Ynys Prydain yn rhestru’r hyn yr oedd yn rhaid i fardd ei feistroli, ac un ohonyn nhw oedd ‘cadw iaith Cymru, ei meistroli a’i chadw rhag cael ei llygru’. Crefft oedd hon, ac fel crefftau eraill yn yr Oesoedd Canol yr oedd ‘gramadeg’ yn un o’r cyfrinachau oedd yn cael eu cadw’n ddirgel gan aelodau’r urdd. | This was not grammar as we recognise it but a name for one aspect of Medieval scholarship. The Tri Chof Ynys Prydain lists the things that a poet had to master and one of them was ‘maintaining the language of Wales, mastering it and keeping it from being corrupted’. This was a craft, and like other crafts in the Middle Ages ‘grammar’ was one of the secrets which were kept a mystery by members of the guild. |

| Y Beibl- William Salesbury Un canlyniad i Ddeddfau Uno Cymru a Lloegr 1536 a 1543 oedd mai Saesneg oedd yr unig iaith oedd yn cael ei chaniatáu yn eglwysi Cymru. Yr oedd William Salesbury, un o ysgolheigion y Dadeni Dysg, yn awyddus i ddod ag addysg newydd y Dadeni i Gymru, a’r un pryd achub enaid pob Cymro. Y ffordd yr aeth ati oedd drwy gyfieithu’r Ysgrythurau i’r Gymraeg ac yn 1567 cyhoeddwyd ei gyfieithiad o’r Testament Newydd a’r Llyfr Gweddi. Er mwyn gallu gwneud hyn, fe ddyfeisiodd ffordd newydd o sillafu geiriau Cymraeg, a cheisio defnyddio tafodieithoedd Cymraeg de a gogledd Cymru yn ei Destament Newydd. Ond, yn anffodus, y canlyniad oedd cyfieithiad a oedd mor ddieithr fel nad oedd neb yn ei hoffi. | The Bible- William Salesbury One result of the Acts of Union 1536 and 1543 between Wales and England was that English was the only language which was permitted in the churches of Wales. William Salesbury, one of the scholars of the Rebirth of Learning, was keen to bring the new scholarship of the Renaissance to Wales, and at the same time to save the soul of every Welsh person. The way he went about it was through translating the Scriptures into Welsh and in 1567 his translation of the New Testament and the Prayer Book was published. In order to be able to do this, he invented a new way of spelling Welsh words, and tried to use Welsh dialects from North and South Wales in his New Testament. But, unfortunately, the result was a translation that was so foreign that no-one liked it. |

| Yr Esgob William Morgan Dyma’r gŵr a gwblhaodd y gwaith o gyfieithu’r Beibl yn 1588. Erbyn y cyfnod hwn, nid oedd y beirdd bellach yn urdd broffesiynol, ac yr oedd yn bosibl i ysgolheigion fel William Morgan, gasglu a dysgu eu ‘cyfrinachau’. Seiliodd ei gyfieithiad ef o’r Beibl ar iaith y beirdd proffesiynol, a chafodd y gwaith ei gwblhau gan Dr John Davies, Mallwyd. | Bishop William Morgan This is the man who completed the work of translating the Bible in 1588. By this period, the poets were no longer a professional guild, and it was possible for scholars such as William Morgan to collect and learn their ‘secrets’. He based his translation of the Bible on the language of the professional poets, and the work was completed by Dr John Davies, Mallwyd. |

| Mae’r dyfyniad canlynol o’r nofel Sgythia gan y diweddar Gwynn ap Gwilym (nofel yn seiliedig ar fywyd Dr John Davies) yn taflu goleuni ar yr hyn a wnaeth Dr Davies: ‘Roedd rhai egwyddorion pwysig wedi dod i’r amlwg wrth ddiwygio’r Testament Newydd: meddalu cytseiniaid – “dywed” nid “dywet”; symleiddio deuseiniaid – “rhagorol” nid “rhagorawl”; newid rhai ffurfiau tafodieithol – troi “minne” a “tithe” yn “minnau” a “tithau” a chywiro rhai ffurfiau anghywir fel “gwnaiff” ac “aiff”.’ | The following quotation from the novel Sgythia by the late Gwynn ap Gwilym (a novel based on the life of Dr John Davies) sheds some light on what Dr Davies did: ‘Some important principles had come to light whilst amending the New Testament: hardening consonants -- “dywed” not “dywet”; simplifying diphthongs – “rhagorol” not “rhagorawl”; changing some dialect forms – replacing “minne” and “tithe” with “minnau” and “tithau” and rectifying some incorrect forms like “gwnaiff” ac “aiff”. |

| Ynglŷn a’r iaith a ddefnyddiwyd yn y Beibl: ‘Mae’n wir na fyddem ni ddim yn defnyddio cystrawen y Beibl ar lafar, ond hi, wedi’r cyfan, ydi cystrawen y beirdd’, sef iaith ar gyfer cyflwyno’r Gymraeg yn gyhoeddus. (Sgythia, tt. 207, 208) | Together with the language which was used in the Bible: ‘It is true that we would not be using the syntax of the Bible when speaking, but for the fact that it is, after all, the syntax of the poets’, namely language for presenting Welsh publically. (Sgythia, pp. 207, 208) |

| Dr John Davies, Mallwyd Yr oedd John Davies wedi bod yn astudio gwaith y beirdd proffesiynol ers deng mlynedd ar hugain. Iddo ef, y beirdd oedd y meistri ar ysgrifennu ac ynganu’r Gymraeg, ac fe luniodd lyfr ar ramadeg y Gymraeg wedi’i seilio ar waith y beirdd. Fel ysgolhaig ei gyfnod, ysgrifennodd ei lyfr, Antiquae Linquae Britannicae . . . rudimenta (a gyhoeddwyd yn 1621), yn Lladin. Yn ei gyfrol A Welsh Grammar (1913), dywed Syr John Morris Jones am lyfr John Davies, ‘the author’s analysis of the Modern literary language is final; he has left to his successors only the correction and amplification of detail.’ | Dr John Davies, Mallwyd John Davies had been studying the work of the professional poets for thirty years. To him, the poets were the masters of writing and pronouncing Welsh, and he fashioned a book on the grammar of Welsh based on the work of the poets. As a scholar of his period, he wrote his book, Antiquae Linquae Britannicae . . . rudimenta (which was published in 1621), in Latin. In his volume A Welsh Grammar (1913), Sir John Morris Jones says of John Davies’ book, ‘the author’s analysis of the Modern literary language is final; he has left to his successors only the correction and amplification of detail.’ |

| Ysgrifennodd John Davies ei Ramadeg ysgolheigaidd yn Lladin, a rhaid cofio nad oedd trwch poblogaeth Cymru yn medru darllen o gwbl; clywed y Beibl yn cael ei ddarllen yn Gymraeg yn yr eglwys fydden nhw. | John Davies wrote his scholarly Grammar in Latin, and we must remember that the bulk of the population of Wales could not read at all; they would hear the Bible being read in Welsh in church. |

| Erbyn diwedd yr 17eg ganrif cwynai nifer o ysgrifenwyr y Gymraeg eu bod yn ei chael hi’n anodd gwybod sut oedd ysgrifennu Cymraeg cywir. Erbyn dechrau’r 18fed ganrif, yr oedd dosbarthwyr llyfrau crefyddol y gogledd yn cwyno nad oedd y bobl yn deall pamffledi wedi eu hysgrifennu gan ysgrifenwyr o’r de, a phobl y de yn cwyno nad oedden nhw’n deall llyfrau wedi eu hysgrifennu yn iaith y gogledd. | By the end of the 17th century a number of writers of Welsh were complaining that they were finding it difficult to know how to write correct Welsh. By the start of the 18th century, distributors of religious books in the North were complaining that people did not understand pamphlets written by writers from the South, and people in the South were complaining that they did not understand books written in the language of the North. |

| Ond o 1737 ymlaen fe ddaeth tro ar fyd. Yn y flwyddyn honno dechreuodd Griffith Jones, Llanddowror, sefydlu rhwydwaith o ysgolion teithiol. Un o’r penderfyniadau pwysicaf a wnaeth Griffith Jones oedd mynnu mai’r Gymraeg fyddai prif gyfrwng y dysgu yn ei ysgolion, a’r Beibl oedd y llyfr y bydden nhw’n ei ddefnyddio i ddysgu darllen ac ysgrifennu. Yn hynny o beth roedd yn gwbl chwyldroadol. Trwy’r ysgolion hyn, crëwyd darllenwyr Cymraeg a galw cyson am gopïau o’r Beibl. | But from 1737 onwards a sea-change occurred. In that year Griffith Jones of Llanddowror began to establish a network of peripatetic schools. One of the most important decisions which Griffith Jones made was to insist that Welsh would be the chief medium of learning in his schools, and that the Bible was the book they would be using to learn reading and writing. In that matter he was completely revolutionary. Through these schools, readers of Welsh were created, as well as a constant call for copies of the Bible. |

| Fe wnaeth y Beibl adfer yr hen undod rhwng de a gogledd, drwy ddarparu iaith sefydlog a safonol y gellid pwyso arni. Ni ddigwyddodd hyn yn Iwerddon na Llydaw, gyda’r canlyniad i’r Wyddeleg a’r Llydaweg ddirywio i fod yn ddim ond nifer o dafodieithoedd. Nid oedd pobl yn deall sylfeini gramadegol Cymraeg y Beibl, ond yr oedd yn gyfrol oedd yn llawn o batrymau yr oedd pobl yn eu darllen ac yn gwrando arnynt ac a fu’n sylfaen i’r iaith am ganrifoedd wedi hynny hyd nes cyrraedd dirywiad yr iaith o ganol yr 20fed ganrif ymlaen. | The Bible restored the old unity between South and North, by providing an established and standard language that could be relied upon. This did not happen in Ireland nor in Brittany, with the result that Irish and Breton deteriorated to be nothing but a number of dialects. People did not understand the grammatical foundation-stones of the Welsh of the Bible, but it was a volume that was full of patterns which people read and listened to and which were a basis for the language for centuries after that until the arrival of the deterioration of the language from the middle of the 20th century onwards. |

| Y Gymraeg 1800 - 2000: William Owen Pughe Yn yr un ffordd ag y daeth William Salesbury dan ddylanwad y Dadeni Dysg yn yr 16eg ganrif, daeth William Owen Pughe (fel Iolo Morganwg) dan ddylanwad syniadau’r Cyfandir am ddatblygiad iaith ar ddechrau’r 19eg ganrif. Y syniad y pryd hwnnw oedd fod ieithoedd yn cael eu hadeiladu trwy gyfuno darnau o hen eiriau’r iaith. Ar ben hynny tyfodd y syniad fod y Gymraeg yn un o ieithoedd hynaf y byd. | Welsh 1800 - 2000: William Owen Pughe In the same way that William Salesbury came under the influence of the Rebirth of Learning in the 16th century, William Owen Pughe (like Iolo Morgannwg) came under the influence of ideas from the Continent about the development of language at the start of the 19th century. The idea that time was that languages are built by uniting pieces of old words of the language. As well as that the idea grew up that Welsh was one of the world’s oldest languages. |

| Jaffeth oedd enw mab hynaf Noa (yn hanes y dilyw yn y Beibl). Mab hynaf Jaffeth oedd Gomer, a Gomer oedd arweinydd y trydydd llwyth ar ddeg (llwyth coll yr Iddewon). Bu Gomer ym Mrwydr Caer Droea (y Groegiaid), ond gadawodd y frwydr ac arwain ei lwyth i Ynys Prydain. Bu Brutus (oedd hefyd wedi dianc o Frwydr Caer Droea) yn bennaeth ar ‘Brutain’, sef gwlad Brutus, a Gomer yn bennaeth ar y rhan honno o Brydain lle roedd y bobl yn siarad y ‘Gomeraeg’. | Japheth was the name of Noah’s eldest son (in the story of the flood in the Bible). Japheth’s eldest son was Gomer, and Gomer was leader of the thirteenth tribe (the lost tribe of the Jews). Gomer had been in the Trojan War, but he left the battle and led his tribe to the Isle of Britain. Brutus (who had also escaped from the Trojan War) was chief of ‘Brutain’, that is the land of Brutus, and Gomer was chief of that part of Britain where people spoke ‘Gomeraeg’. |

| Yr oedd llenorion y cyfnod yn gytûn mai Pughe oedd y prif awdurdod ar y Gymraeg, ac mai ef a’i hachubodd fel iaith dysg. Ond pan aeth ysgolheigion ati i astudio’r iaith yn wyddonol ar ddiwedd y ganrif, cafwyd nad oedd ganddo wybodaeth sicr o’r Gymraeg o gwbl, a bod ei ddamcaniaethau ffugwyddonol wedi gwneud drwg anfesuradwy i’r iaith. | The literary people of the period were unanimous that Pughe was the chief authority on Welsh and, and that it was he who had saved it as a language of learning. But when scholars set to work to study the language scientifically at the end of the century, it was found that he did not have a sure knowledge of Welsh at all, and that his pseudo-scientific hypotheses had done immeasurable harm to the language. |

| Sylw John Morris-Jones ar Ramadeg William Owen Pughe oedd: "It stands at the opposite pole [i Ramadeg John Davies]. It is written on the same principle as the [Pughe] dictionary, and represents the language not as it is, or ever was, but as it might be if any suffix could be attached mechanically to any stem. To the author truth meant conformity with his theory; facts perverse enough to disagree were glossed over." | John Morris-Jones’s comment on William Owen Pughe’s Grammar was: "It stands at the opposite pole [to John Davies' Grammar]. It is written on the same principle as the [Pughe] dictionary, and represents the language not as it is, or ever was, but as it might be if any suffix could be attached mechanically to any stem. To the author truth meant conformity with his theory; facts perverse enough to disagree were glossed over." |

| Er mwyn argyhoeddi’r rhai a fu’n edmygu Pughe, bu raid i’r ddau farchog Syr John Rhys a Syr John Morris-Jones ladd yn ddidrugaredd ar gyfeiliornadau gwaith William Owen Pughe er mwyn cyflawni’r orchest Herciwleaidd o garthu stablau’r iaith. | In order to convince those who had admired Pughe, there was need for the two knights Sir John Rhys and Sir John Morris-Jones to criticise mercilessly the errors in the work of William Owen Pughe in order to complete the Herculean task of cleansing the stables of the language. |

| Addysg a’r Gymraeg Ddechrau’r 20fed ganrif yr oedd dau gorff yn gyfrifol am ddarparu arholiadau Cymraeg, sef Bwrdd Canol Cymru, a sefydlwyd yn 1896, ac Adran Gymreig y Bwrdd Addysg, a sefydlwyd yn 1907. O. M. Edwards oedd yr arolygydd a benodwyd gan y Bwrdd Addysg newydd. | Education and Welsh At the start of the 20th century there were two bodies responsible for providing Welsh exams, namely the Central Welsh Board, which was established in 1896, and the Welsh Department of the Board of Education, which was established in 1907. O. M. Edwards was the inspector who was appointed by the new Board of Education. |

| Yn arholiadau Bwrdd Canol Cymru: ‘examiners emphasized the need for candidates sitting the Central Welsh Board Examinations in Welsh Language and literature to demonstrate thorough knowledge of grammar, including accidence, the mutation of initial consonants, the conjugation of verbs and prepositions and the analysis of sentences.’ | In the examinations of the Central Welsh Board: ‘examiners emphasised the need for candidates sitting the Central Welsh Board Examinations in Welsh Language and literature to demonstrate thorough knowledge of grammar, including accidence, the mutation of initial consonants, the conjugation of verbs and prepositions and the analysis of sentences.’ |

| Ymateb hallt O. M. Edwards i hyn oedd: ‘The minds of children seem to be very mechanical, their memory is overburdened...the Central Welsh Board should now consider to what extent their rigid and unintelligent examination system may be the cause of the wooden and unintelligent type of mind of which their examiners complain.’ | O. M. Edwards’ harsh response to this was: ‘The minds of children seem to be very mechanical, their memory is overburdened...the Central Welsh Board should now consider to what extent their rigid and unintelligent examination system may be the cause of the wooden and unintelligent type of mind of which their examiners complain.’ |

| Dyma syniadau tra gwahanol i’w gilydd gan ddau o gewri’r iaith yn hanner cyntaf yr 20fed ganrif. Yr oedd Syr John-Morris Jones yn ystyried y dull gramadegol o ddysgu Lladin fel y delfryd ar gyfer dysgu Cymraeg yn yr ysgolion: ‘The written language has been corrupted not only under the influence of false etymological theories, but also in the opposite direction by the substitution of dialectal forms for literary forms.’ | Here are ideas that are very different from each other, from two of the giants of the language in the first half of the 20th century. Sir John Morris-Jones considered the grammatical method of learning Latin as the ideal for learning Welsh in schools: : ‘The written language has been corrupted not only under the influence of false etymological theories, but also in the opposite direction by the substitution of dialectal forms for literary forms.’ |

| Ar y llaw arall, mae’n werth cofio fod Gramadeg John Davies, Mallwyd (ac iaith y Beibl), y mae Syr John yn ei gefnogi yn ddisgrifiad o iaith oedd yn hen ffasiwn a braidd yn ‘farddonllyd’ hyd yn oed yn yr 17eg ganrif pan luniwyd y Gramadeg. Un o ganlyniadau anffodus holl astudiaethau Syr John o’r gweithiau hynny (gwaith y beirdd a John Davies, Mallwyd) oedd ei fod yn tueddu ar brydiau i ddiystyru rhai o arferion ieithyddol ei gyfnod ei hun a nodweddion oedd wedi tyfu’n gwbwl naturiol yn yr iaith. Yr oedd Syr John yn cynnig safon o Gymraeg clasurol, ysgrifenedig, yr oedd bron yn amhosibl i unrhyw un ei llwyr feistroli. | On the other hand, it is worth remembering that John Davies of Mallwyd’s Gramadeg (and the language of the Bible) that Sir John supports is a description of language that was old-fashioned and rather ‘pretentiously poetic’ even in the 17th century when the Gramadeg was fashioned. One of the unfortunate results of all Sir John’s studies of those works (the work of the poets and John Davies, Mallwyd) was that he tended on occasions to disdain some of the linguistic practices of his own period and characteristics which had grown up completely naturally in the language. Sir John was proposing a standard of classical, written Welsh, it was almost impossible for anyone to master completely. |

| Yn gwbl groes i agwedd Syr John, roedd O. M. Edwards yn dymuno gweld disgyblion yn ysgrifennu yn eu tafodieithoedd Cymraeg eu hunain. | Completely contrary to Sir John’s attitude, O. M. Edwards wanted to see pupils writing in their own Welsh dialects. |

| Roedd am weld plant yn defnyddio Cymraeg naturiol ei gyfnod, gan sylweddoli y gallai gorbwyslais ar darddiad hanesyddol geiriau a chywirdeb ieithyddol, hynafol wahanu’r iaith oedd yn cael ei hysgrifennu oddi wrth y rhai oedd yn ei siarad yn naturiol. Ei ateb oedd cyflwyno mwy o ymarferion ysgrifennu creadigol mewn arholiadau Cymraeg. Barn pobl fel O. M.Edwards a enillodd y dydd hefyd yn y dadleuon ynghylch sut i ddysgu Saesneg. | He wanted to see children using the natural Welsh of his period, realising that an over-emphasis on the historical derivation of words and archaic linguistic correctness could separate the language that was being written from the people speaking it naturally. His answer was to introduce more creative writing exercises into Welsh exams. It is the opinion of people such as O. M. Edwards that also won the day in the arguments about how to teach English. |

| Mae’r gyfrol Examining the Secondary Schools of Wales 1896–2000 yn edrych ar sylwadau arholwyr arholiadau Cymraeg yn y cyfnod 1930–2000. Yn fyr, mae’n nodi’r cynnydd yn ‘weaknesses in sentence construction and an ignorance of grammar’. | The volume Examining the Secondary Schools of Wales 1896–2000 looks at the comments of examiners of Welsh exams in the period 1930 – 2000. In short, it notes the growth of ‘weaknesses in sentence construction and an ignorance of grammar’. |

| Erbyn yr 1980au yr oedd yr arholwyr yn gofyn, ‘Is it not time, for the sake of linguistic correctness, to return to some practices that were acceptable many years ago and believe again that there was value in understanding the nature of a language?’ | By the 1980s the examiners were asking, ‘Is it not time, for the sake of linguistic correctness, to return to some practices that were acceptable many years ago and believe again that there was value in understanding the nature of a language?’ |

| Y broblem gyda safbwynt O. M. Edwards oedd fod y cymdeithasau Cymraeg eu hiaith yr oedd ef am i blant Cymru eu hefelychu wedi diflannu. Eto, yr oedd arbenigwyr yn y maes addysg am gadw’r model o ddysgu iaith a gyflwynwyd ganddo. Gan fod model gwreiddiol O. M. Edwards wedi diflannu, aethon nhw ati i greu model newydd o iaith lafar, sef Cymraeg Byw. | The problem with O. M. Edwards’ viewpoint was that the Welsh-speaking societies he wanted the childen of Wales to imitate had disappeared. Nevertheless, specialists in the field of education wanted to keep the model of language learning introduced by him. As O. M. Edwards’ original model had disappeared, they went to work to create a new model of spoken language, namely Cymraeg Byw. |

| Yr un hanes sydd i Gymraeg Byw ag oedd i ymdrechion ieithyddol William Salesbury ganrifoedd cyn hynny. Nid oedd y Cymry Cymraeg yn siarad nac yn darllen y math yma o Gymraeg. O ran addysg, yr oedd yn golygu bod yn rhaid i ddysgwyr dysgu math o Gymraeg nad oedd neb yn ei siarad, cyn symud ymlaen wedyn i ddysgu math arall o Gymraeg a oedd yn cael ei siarad. | Cymraeg Byw has the same history as the linguistic efforts of William Salesbury centuries beforehand. Welsh-speaking Welsh people neither spoke nor read this kind of Welsh. Regarding education, it meant that learners needed to learn a type of Welsh that no-one spoke, before then moving on to learn another kind of Welsh, which was spoken. |

| Unwaith eto, y traddodiad barddol ym mherson y prifardd, y prifathro a’r awdur plant poblogaidd T. Llew Jones a gamodd i’r bwlch drwy wrthryfela yn erbyn y drefn a dangos pam na allai byth weithio. | Once again, the poetic tradition in the the person of the chief-poet, headmaster and popular childrens’ author T. Llew Jones stepped into the breach by revolting against the system and showing why it could never work. |

| Heddiw, mae’r cwestiwn a holwyd 40 mlynedd yn ôl ynghylch ‘the value in understanding the nature of a language’ yn dal heb ei ateb. Rwyf wedi dechrau ar ymgais i gyflwyno rhai o ‘reolau gramadegol’ y Gymraeg mewn ffordd nad yw’n seiliedig ar adnabyddiaeth o deithi’r iaith Ladin ac nad yw’n dibynnu ar fedru siarad Cymraeg chwaith. Mae’n seiliedig ar gyflwyno ‘an understanding of the nature of language’ drwy adeiladu brawddegau Cymraeg allan o flociau gramadegol o wahanol liw. Y cam cyntaf oedd y gyfrol D.I.Y Welsh. Yr ail gam (rwy’n gobeithio) fydd troi’r holl broses yn gêm y gellir ei chwarae (heb i neb teimlo’n dwp a heb bwysau) yn debyg i ‘Monopoli’. | Today, the question which was asked 40 years ago regarding ‘the value in understanding the nature of a language’ is still unanswered. I have begun an endeavour to present some of the ‘grammatical rules’ of Welsh in a way that isn’t based on recognition of the traits of the Latin language, and which doesn’t depend on being able to speak Welsh either. It’s based on presenting ‘an understanding of the nature of language’ through building Welsh sentences out of grammatical blocks of different colours.The first step was the volume D.I.Y. Welsh. The second step (I hope) will be turning the whole process into a game that can be played (without anyone feeling stupid and without pressure) similar to ‘Monopoly’. |

| Cawn weld... | We’ll see... |

Colofn 4, Medi 2018

Yr Anoeth Sisiffysaidd: Creu Geiriadur Cymraeg Gomer

The Sisyphean Quest: Creating Geiriadur Cymraeg Gomer

| Roedd Geiriadur Cymraeg Gomer yn gomisiwn ar y cyd rhwng CBAC (Cyd-Bwyllgor Addysg Cymru) ac AADGOS i ddechrau ond CBAC ac AdAS (Adran Addysg a Sgiliau Llywodraeth Cymru) erbyn y diwedd i lunio geiriadur esboniadol, safonol ar gyfer myfyrwyr ysgolion uwchradd. | To start with, Geiriadur Cymraeg Gomer was a joint commission between the WJEC (the Welsh Joint Education Committee) and AADGOS [Adran Addysg, Dysgu Gydol Oes a Sgiliau; Wales Department of Education, Lifelong Learning and Skills], although by the end of the process this had become the WJEC and DfES (the Welsh Government’s Department for Eduaction and Skills), to fashion a standard, expository dictionary for students in secondary schools. |

| Yr oedd yn gam mawr iawn o eiriadur Geiriadur Gomer yr Ifanc (GGI) a oedd yn ateb gofynion cyffredinol geiriadur Cymraeg: | It was a great step indeed from the dictionary Geiriadur Gomer yr Ifanc (GGI) which satisfied the general requirements of a Welsh dictionary: |

| 1. Beth yw cenedl (enw) 2. Sut y mae sillafu (ffurfiau anghywir e.e. cauodd; ty; penderfynnu) 3. Beth yw ystyr ‘brithwaith’ (cyn GGI yr unig ateb oedd troi at ddiffiniad y gair yn Saesneg ond yn GGI rhoddir diffiniad Cymraeg) 4. A yw’r gair yn achosi treiglad 5. Beth yw’r gair Cymraeg am y gair Saesneg xxx (sef Adran Saesneg/Cymraeg) | 1. What is the gender (for nouns) 2. How is it spelled (listing incorrect forms, e.g. cauodd [caeodd, ‘he/she/it closed]; ty [tŷ, ‘house’] ; penderfynu [penderfynnu, ‘to decide’]) 3. What is the meaning of ‘brithwaith’ (before GGI the only answer was to turn to the definition of the word in English but in GGI the Welsh definition is given) 4. Does the word cause a mutation 5. What is the Welsh word for the English word xxx (that is an English/Welsh Section) |

| Ond yn awr, yr oedd angen cynnwys rhai miloedd o dermau technegol yn y meysydd hynny oedd yn cael eu hastudio drwy gyfrwng y Gymraeg. Rhan o’r broses newydd hon oedd derbyn cyngor gan eiriadurwyr Geiriadur Prifysgol Cymru ac arbenigwyr gramadegol. | But now, it was necessary to include some thousands of technical terms in those fields that were being studied through the medium of Welsh. Part of this new process was getting advice from the lexicographers at Geiriadur Prifysgol Cymru and specialists on grammar. |

| Rhai o ganlyniadau’r ymgynghori oedd: 1. Ei fod yn eiriadur cyfoes 2. Byddai’n canolbwyntio ar ffurfiau Cymraeg safonol 3. Yn achos enwau oedd yn gallu bod yn wrywaidd neu yn fenywaidd, byddai’n nodi’r genedl fwyaf cyffredin neu a oedd un ffurf yn cael ei defnyddio yn bennaf yn y Gogledd neu yn y De. 4. Yr oedd rhaid cyflwyno pob gair yn unol â’i ran ymadrodd, e.e: | Some of the results of the consultaion were that: 1. It is a contemporary dictionary 2. It would concentrate on standard Welsh forms 3. In the case of nouns that could be masculine or feminine, it would note the most common gender or whether one form was used mainly in North Wales or in South Wales. 4. It was necessary to introduce every word according to what part of speech it was, e.g: |

| deall1 be fel berfenw defnyddiwn ferfenwau yn y diffiniad canfod ystyr to understand, to comprehend deall2 eg fel enw defnyddiwn enwau yn y diffiniad y gallu neu’r gynneddf intellect, understanding coch1 eg fel enw diffinio yn defnyddio enwau lliw gwaed neu aeron aeddfed coed celyn red coch2 ans [coch•] (cochion) fel ansoddair, diffinio yn ddisgrifiadol o liw gwaed, tomato aeddfed, etc. red | deall1 verbnoun [we show verbnouns being used as verbouns in the definition] discern meaning to understand, to comprehend deall2 masculine noun [we show nouns being used as nouns in the definition] the ability or the faculty intellect, understanding coch1 masculine noun [as a noun, define using nouns] the colour of blood or mature holly berries red coch2 adjective [coch•] (cochion) [as an adjective, define descriptively] blood-coloured, coloured like a mature tomato, etc red |

| Nid yw’r manion hyn yn ymddangos yn bwysig, ond llwyddo i gyflawni’r lefel yma o gywirdeb a chysondeb yn gyson drwy’r Geiriadur sy’n ei wneud yn waith awdurdodol. | These minute details do not appear important, but succeeding to convey this level of correctness and consistency in exactly the same way throughout the Geiriadur is what makes it an authoritative work. |

| Gan fod y testun yn cael ei osod ar gronfa ddata electronig (a luniwyd gan Nudd, fy mab) bu’n gymharol hawdd sicrhau ein bod yn dilyn yr un patrwm drwy’r llyfr. Yr oedd hefyd yn golygu y byddem yn gallu newid pethau, e.e un peth bach oedd, ein bod ar y dechrau, yn gosod brawddegau enghreifftiol mewn cromfachau. | Because the text is underpinned by an electronic database (which was constructed by Nudd, my son) it was comparatively easy to ensure that we followed the same pattern throughout the book. It also meant that we could change things, e.g. one small thing was that, at the beginning, we were placing example sentences in brackets. |

| meddwl2 be [meddyli•2 3 un. pres. meddwl/meddylia; 2 un. gorch. meddwl/meddylia] defnyddio’ch rheswm, dod i rai casgliadau, cael syniad, dod i benderfyniad (Roeddwn i’n meddwl ei bod hi’n ffilm dda. Rwy’n meddwl yr af i i nofio yfory os bydd hi’n braf.); credu, tybio to think, to consider. | meddwl2 verbnoun [meddyli•2 3 sing. pres. meddwl/meddylia; 2 sing. imper. meddwl/meddylia] to use your reason, to come to some conclusions, to have an idea, to reach a decision (I thought it was a good film. I think I’ll go swimming tomorrow if it’s fine.); credu [to believe], tybio [to suppose] to think, to consider. |

| Ond wedyn penderfynu nad oedd eisiau cromfachau yn ogystal â phrint italig, dilëwyd y cromfachau defnyddio’ch rheswm, dod i rai casgliadau, cael syniad, dod i benderfyniad, Roeddwn i’n meddwl ei bod hi’n ffilm dda. Rwy’n meddwl yr af i i nofio yfory os bydd hi’n braf.; credu, tybio to think, to consider. | But then we decided that we did not want brackets as well as italic type, and the brackets were removed: to use your reason, to come to some conclusions, to have an idea, to reach a decision, I thought it was a good film. I think I’ll go swimming tomorrow if it’s fine.; credu [to believe], tybio [to suppose] to think, to consider |

| Ond sylwch yr oedd cael gwared â’r cromfachau yn golygu ein bod yn gorfod ychwanegu coma. | But notice that getting rid of the brackets meant that we had to add a comma. |

| Dyma lefel y manylder oedd ei hangen. Gwnaethon ni sganio drwy’r testun cyfan (43,000 o ddiffiniadau) dros 400 o weithiau er mwyn sicrhau cysondeb cyn cyhoeddi’r Geiriadur. | This is the level of detail that was needed. We scanned through the enire text (43,000 definitions) over 400 times in order to ensure consistency before publishing the Geiriadur. |

| Berfau a Berfenwau Dyma un o feysydd mwyaf cymhleth y Gymraeg. Yr oeddwn yn awyddus i wneud dau beth: | Verbs and Verbnouns This is one of the most complex fields in the Welsh language. I was keen to do two things: |

| 1. Ceisio dosbarthu’r berfau yn ôl y ffordd yr oeddynt y cael eu rhedeg (fel oedd yn cael ei gwneud yn achos berfau Ffrangeg a berfau Almaeneg yn y geiriaduron Cymraeg yn ymwneud â’r ddwy iaith hynny). | 1. To try and classify the verbs according to the way they were conjugated (as was done in the case of French and German verbs in the Welsh dictionaries dealing with these two languages). |

| 2. Cofnodi’r arddodiaid oedd yn dilyn berfau Cymraeg a’r defnydd o’r arddodiaid. Yr oedd Sabine Heinz yn ei chyfrol Welsh Dictionaries in the Twentieth Century: A Critical Analysis, wedi tynnu sylw at nifer o ddiffygion geiriaduron Cymraeg, ac yn eu plith yr oedd y defnydd o arddodiaid berfol. Yr oedd Peter Wyn Thomas yn ei gyfrol Gramadeg y Gymraeg wedi dangos y ffordd ymlaen yn y maes hwn fel yn nifer o feysydd eraill a nodwyd gan Sabine Heinz, ond wrth gwrs nid oedd lle mewn llyfr gramadeg i gynnwys rhestr gynhwysfawr o’r holl ffurfiau. | 2. To note the prepositions that followed Welsh verbs, and how these were used. Sabine Heinz in her volume Welsh Dictionaries in the Twentieth Century: A Critical Analysis, had drawn attention to a number of deficiencies in Welsh dictionaries, and amongst them was the use of verbal prepositions. Peter Wyn Thomas in his volume Gramadeg y Gymraeg had shown the way forward in this field as in a number of other fields, as noted by Sabine Heinz, but of course there was not space in book of grammar to include a comprehensive list of all the forms. |

| Gyda chymorth yr Athro Robert Owen Jones a gwaith dygn ac arbenigedd Mair Treharne (CBAC) llwyddwyd i ddosbarthu berfau’r Gymraeg i 20 dosbarth, gan ddangos unrhyw ffurfiau eithriadol dan gofnod y ferf unigol. | With the help of Professor Robert Owen Jones and the assiduous work and expertise of Mair Treharne (WJEC) we succeeded in categorizing the verbs of the Welsh language into 20 classes, showing any exceptional forms under the entry for the individual verb. |

| Geiriau Technegol Mae’r Geiriadur yn cynnwys termau technegol yn y meysydd canlynol: | Technical Words The Geiriadur contains technical terms in the following fields: |

| Addysg (Education) | Amaeth (Agriculture) | Anatomeg (Anatomy) | Anthropoleg (Anthropology) |

| Archaeoleg (Archaeology) | Athroniaeth (Philosophy) | Biocemeg (Biology) | Botaneg (Botany) |

| Celfyddyd (Art) | Cemeg (Chemistry) | Cerddoriaeth (Music) | Chwaraeon (Sports) |

| Coginio (Cookery) | Crefydd (Religion) | Cyfraith (Law) | Cyfrifiadureg (Computing) |

| Cyllid (Finance) | Daeareg (Geology) | Daearyddiaeth (Geography) | Drama |

| Ecoleg (Ecology) | Economeg (Economics) | Electroneg (Electronics) | Entomoleg (Entomology) |

| Ffiseg (Physics) | Ffisioleg (Physiology) | Geneteg (Genetics) | Gramadeg (Grammar) |

| Gwaith coed (Woodwork) | Gwleidyddiaeth (Politics) | Gwniadwaith (Needlework) | Hanes (History) |

| Ieithyddiaeth (Linguistics) | Llenyddiaeth (Literature) | Mathemateg (Mathematics) | Mecaneg (Mechanics) |

| Meddygaeth (Medicine) | Meteleg (Metelurgy) | Meteoroleg (Meteorology) | Morwriaeth (Navigation) |

| Pensaernïaeth (Architecture) | Rhesymeg (Psychiatry) | Seicoleg (Psychology) | Seryddiaeth (Astronomy) |

| Swoleg (Zoology) | Technoleg (Technology) |

| Er bod rhestri o dermau ar gael, nid oedd y termau yn cael eu diffinio. Felly bu raid galw ar arbenigwyr yn y meysydd hyn i wirio’r diffiniadau Cymraeg. | Although there were lists of terms available, the terms were not being defined. So it was necessary to call on experts in these fields to check the Welsh definitions. |

| Ar ben hynny bu golygyddion CBAC yn gwirio’r diffiniadau er mwyn sicrhau bod y termau cywir yn cael eu defnyddio mewn diffiniad, e.e: | As well as that the WJEC’s editors checked the definitions in order to ensure that the correct terms were being used in a definition, e.g: |

| gwasgedd eg (gwasgeddau) 2 FFISEG grym pob uned o arwynebedd wedi’i roi ar ongl sgwâr i arwyneb (e.e. mae gwasgedd yr atmosffer tua 105 newton i bob metr sgwâr) (air) pressure pwysedd gwaed MEDDYGAETH pwysedd gwaed yn y system cylchrediad gwaed sydd ynghlwm wrth rym a chyfradd curiad y galon a diamedr ac elastigedd muriau’r rhydwelïau blood pressure. | gwasgedd masculine noun (gwasgeddau) 2 PHYSICS the force per unit area on a surface set at right-angles to the force (e.g. atmospheric pressue is about 105 newton per meter square) (air) pressure pwysedd gwaed MEDICINE the pressure of the blood in the blood circulatory system which is connected with the force and the rate of the heartbeat and the diameter and elasticity of the arteries blood pressure. |

| Hefyd yr oedd angen cyngor ar sut i ynganu termau fel: centimetr; cerebelwm, abdwcent etc. | Also, advice was needed on how to pronounce terms like: centimetr; cerebelwm, abdwcent etc. |

| Isbenawdau ac Ymadroddion Yn deillio o gynnwys termau technegol cafwyd llawer o Isbenawdau technegol, e.e: | Subheadings and Phrases As a result of including technical terms many technical subheadings cropped up under the common head-word, e.g: |

| llid eg (llidiau) MEDDYGAETH gwres, cochni a chwydd poenus mewn rhannau o’r corff, wedi’u hachosi fel adwaith i haint neu niwed inflammation llid falfiau’r galon endocarditis; llid y bilen lefn sy’n gorchuddio’r siambrau y tu mewn i’r galon a’i falfiau endocarditis llid pibell y bledren wrethritis; llid yr wrethra urethritis llid y berfeddlen peritonitis; cyflwr meddygol lle mae’r peritonëwm yn mynd yn llidus peritonitis llid y bledren etc. etc. | llid masculine noun (llidiau) MEDICINE warmth, reddening, and painful swelling in parts of the body, caused as a reaction to disease or damage inflammation llid falfiau’r galon endocarditis; inflammation of the smooth membrane that protects the chambers within the heart and its valves endocarditis llid pibell y bledren urethritis; inflammation of the urethra urethritis llid y berfeddlen llidus peritonitis; a medical condition where the peritoneum becomes inflamed peritonitis llid y bledren etc. etc. |

| Ac yr oedd yn bwysig gwahanu’r rhain oddi wrth Ymadroddion, e.e. Isbenawdau asgwrn y pen [ANATOMEG] creuan; y rhan o’r benglog sy’n gorchuddio’r ymennydd cranium asgwrn yr ên [ANATOMEG] genogl; un o esgyrn yr ên, yn enwedig yr asgwrn isaf jawbone | And it was important to separate these from Phrases, e.g. Isbenawdau [Subheadings] asgwrn y pen [ANATOMY] cranium; the part of the skull that protects the brain cranium asgwrn yr ên [ANATOMY] mandible; one of the bones in the jaw, especially the lowest bone jawbone |

| Ymadroddion asgwrn i’w grafu cynnen i’w chodi a bone to pick asgwrn y gynnen achos cweryl neu ffrae bone of contention | Ymadroddion [Phrases] asgwrn i’w grafu a quarrel to be started a bone to pick asgwrn y gynnen the cause of a quarrel or fight bone of contention |

| Y peth i sylweddoli yma yw bod y rhain yn cael eu diffinio yn Gymraeg, nid ydynt yn dibynnu ar y cyfieithiad Saesneg. | The thing to appreciate here is that these are defined in Welsh, they do not depend on the English translation. |

| Cywair Penderfynwyd cynnwys cyngor ar y geiriau hynny fyddai’n cael eu defnyddio mewn sefyllfaoedd neu gyweiriau arbennig: | Register It was decided to include advice on those words which would be used in special situations or explanations: |

| Cywair aflednais anffurfiol di-chwaeth difrïol ffigurol ffurfiol gair tafodieithol hanesyddol hen ffasiwn hynafol llafar llenyddol rheg safonol yn y De safonol yn y Gogledd sarhaus annerbyniol tafodieithol yn y De tafodieithol yn y Gogledd technegol | Register vulgar informal tasteless serious figurative formal dialect word historical old-fashioned archaic spoken literary swear-word standard in the South standard in the North unacceptably offensive dialectical in the South dialectical in the North technical |

| Wrth gynnwys y pethau newydd hyn, daeth yn fwy fwy clir na fyddai lle i bopeth mewn un gyfrol, felly penderfynwyd: | By including these new features, it became more and more clear that there would not be space for everything in one volume, and so it was decided: |

| • Peidio â chynnwys diarhebion • Cyfyngu ar nifer y geiriau cyfystyr Cymraeg i’r ddau neu dri agosaf eu hystyr • Peidio â chynnwys yr ‘Ymadroddion’ yn Adran Saesneg-Cymraeg y geiriadur | • Not to include proverbs • To restrict the number of synonymous Welsh words to the two or three closest in meaning • Not to include the ‘Phrases’ in the English-Welsh Section of the dictionary |

| Diolch i arbenigedd Gwasg Gomer, cyhoeddwyd y cynnwys i gyd mewn un gyfrol o 1,400 o dudalennau – y llyfr mwyaf a gyhoeddwyd gan Wasg Gomer mewn canrif o argraffu llyfrau. Yr oedd eu llwyddiant yn deillio o adnabyddiaeth drylwyr y wasg o’r wynebau teip mwyaf addas a’r papur arbennig a ddefnyddiwyd ganddynt. | Thanks to the expertise of Gwasg Gomer, all the contents was published in one volume of 1,400 pages – the biggest book published by Gwasg Gomer in a century of printing books. Their success came down to the press’s exhaustive knowledge of the most suitable typefaces, and the special paper they used. |

| Dyma ddyfyniadau allan o adolygiad trylwyr Christine Jones yn y Traethodydd o’r hyn a gafodd hi yn y Geiriadur: | Here are some quotations from Christine Jones’ comprehensive review in Y Traethodydd regarding what she found in the Geiriadur. |

| • Nifer o eiriau newydd sbon • Hen eiriau tafodieithol • Priod-ddulliau lliwgar • Mae’r Tabl Berfau yn syml ac yn effeithiol • 43,000 o gofnodion yn diffinio ystyr gair ac yn cynnig cyfystyron • Amrywiaeth eang o eiriau poblogaidd newydd (e.e. selfie) • Ymadroddion a phriod-ddulliau nad ydynt yn aml i’w gweld o fewn cloriau geiriadur traddodiadol • Defnyddir brawddegau enghreifftiol i’w hesbonio’n fanylach • Diffiniadau manwl nas ceir mewn geiriaduron traddodiadol yn aml • Yr ystod eang o dermau pwnc arbenigol • Mae labeli maes yn ddefnyddiol • Ond yn fwy gwerthfawr, y labeli defnydd – llenyddol; difrïol; di-chwaeth etc. • Yn wahanol i eiriaduron eraill yw’r ffocws ar rai agweddau gramadegol a braf cael y rhain i gyd yn hwylus mewn un gyfrol • Adran Saesneg – Cymraeg | • A number of brand-new words • Old dialect words • Colourful idioms • The Verb Table is simple and effective • 43,000 entries defining the meaning of a word and offering synonyms • A wide variety of new popular words (e.g. selfie) • Phrases and idioms that are not often seen within the covers of a traditional dictionary • Example sentences are used to explain things in more detail • Detailed definitions which are not often found in traditional dictionaries • The wide range of terms in specialist fields • The topical labels are useful • But more valuable are the usage labels – literary; serious; tasteless etc. • The focus on some grammatical aspects is different from that of other dictionaries, and it is a good thing to find all of these conveniently in one volume • An English – Welsh Section |

| Fel yr awgrymwyd ar y dechrau, sut oedd dringo’r ‘Mynydd Annrinagdwy’ hwn? – un cam ar y tro. | As was alluded to at the start – how did we climb this ‘Mount Impossible’? – one step at a time. |

| 1. Teithiodd Nudd fy mab gam wrth gam gyda fi pob cam o’r ffordd o’r Gweiadur i hwn 2 Cefais gymorth tîm bach o gyfeillion cwbl ymrwymedig – Dr. Dyfed Elis Gruffydd; Elinor Wyn Reynolds, Glenys Mair Roberts; ac wedyn Sioned Wyn a Gwenda Lloyd Wallace. Daeth Mair Treharne o CBAC â chwistrelliad o ocsigen inni fedru gorffen esgyn i’r brig. Ond y ‘Sherpa’ a gariodd lawer o’r pwysau o’r cychwyn cyntaf oedd Susan Jenkins o CBAC na fyddai’r Geiriadur wedi cael ei gwblhau oni bai amdani hi. | 1. My son Nudd travelled step by step with me, every step of the way from the Gweiadur to this book 2. I had the support of a small team of completely devoted friends – Dr. Dyfed Elis Gruffydd; Elinor Wyn Reynolds, Glenys Mair Roberts; and then Sioned Wyn and Gwenda Lloyd Wallace. Mair Treharne from the WJEC hefted supplies of oxygen so that we could complete the task of reaching the summit. But the ‘Sherpa’ who bore much of the burden from the very start was Susan Jenkins of the WJEC – without her the Geiriadur would not have been completed. |

| Os oedd gan y Brenin Arthur ei farchogion i gyflawni anoethau, dyma farchogion bord gron llyfrgell Gwasg Gomer yn Llandysul a diolch iddynt bob un. | If King Arthur had his knights to complete quests, these are the knights of the round table at Gwasg Gomer in Llandysul – I salute every one of them. |

gomer.co.uk/geiriadur-cymraeg-gomer.html

Colofn 3, Awst 2018

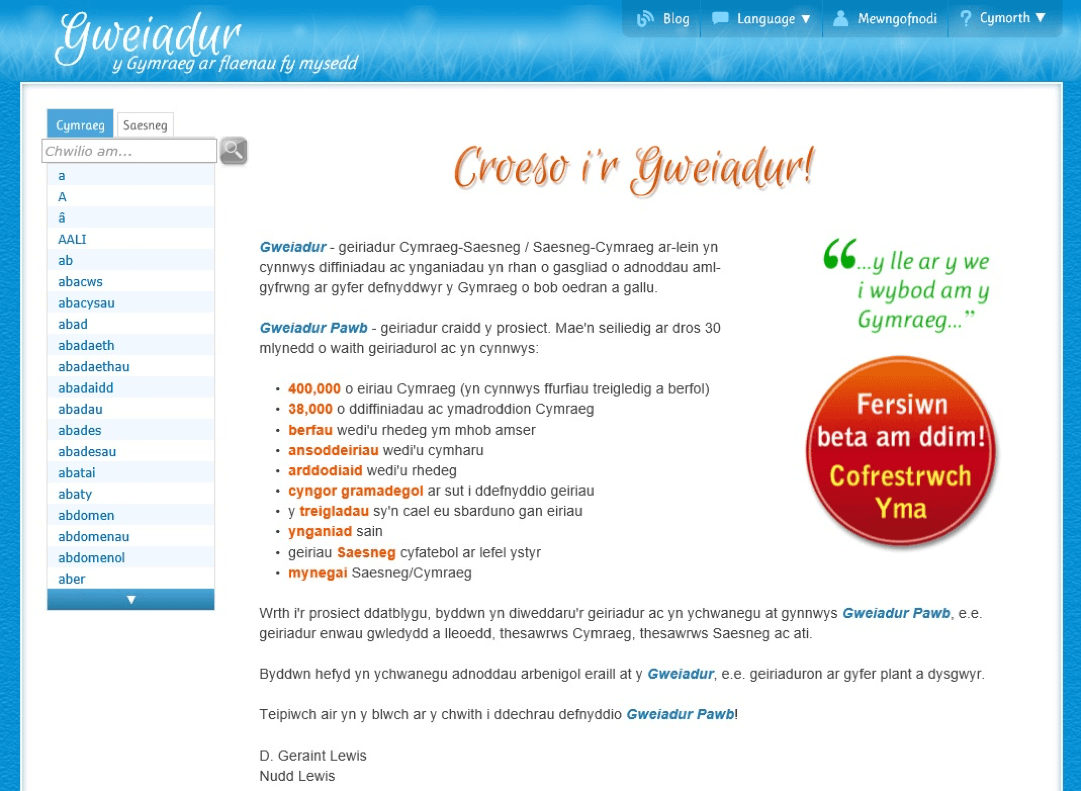

I mewn i’r oes ddigidol: creu adnau gwybodaeth ddigidol ddwyieithog, gweiadur.com

Into the digital age: creating a bilingual digital knowledge repository, gweiadur.com

| Argraffwyd Geiriadur Gomer i’r Ifanc (GGI) yn yr hen ffordd ac rwy’n cofio eistedd nesaf at Gari a fyddai’n gludo stripiau o destun ar ddalen arbennig i greu proflen dudalen. Bûm yn ffodus iawn yn gweithio gyda thîm o grefftwyr a fu’n gyfrifol am fy holl gyfrolau cynnar – Louise Jones, cysodydd GGI a Geiriadur Cymraeg Gomer, Elgan Davies dylunydd y Cyngor Llyfrau, Dr Dyfed Elis Gruffydd golygydd Gwasg Gomer a Gari. Yn achos GGI, yr oedd dwy golofn o destun a lluniau, ac wrth gwrs, yn aml iawn ni fyddai lle i’r llun ar bwys y gair priodol, ac yr oedd rhaid dod o hyd i ateb. | Geiriadur Gomer i’r Ifanc (GGI) was published in the old-fashioned way and I remember sitting next to Gari who would glue strips of text onto special sheets of paper to make page proofs. I was very fortunate working with a team of craftspeople who were responsible for all my early volumes – Louise Jones, the compositor for GGI and Geiriadur Cymraeg Gomer, Elgan Davies the designer for the Cyngor Llyfrau (Books Council), Dr Dyfed Elis Gruffydd the editor at Gwasg Gomer and Gari. In the case of GGI, there were two columns of text and pictures, and of course, very often there wouldn’t be space for the picture besides the appropriate word, and we’d have to find a solution. |

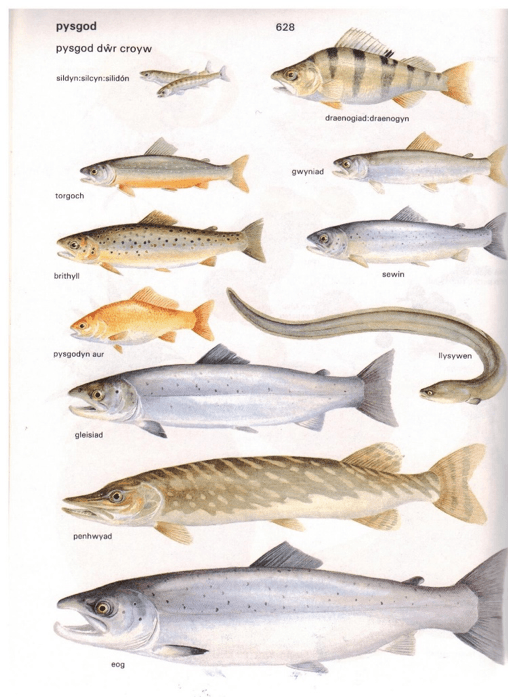

| Fred Deane oedd wedi tynnu lluniau’r gyfrol, arlunydd profiadol iawn ac y mae’n werth sylwi ar fanylder ei luniau yn y gyfrol. It was Fred Deane, a very experienced artist, who drew the pictures for the volume, and it’s worth commenting on the detail of his pictures in the volume. | A dyma un o luniau godidog Owen Williams Trefenter: And here is one of Owen Williams Trefenter’s outstanding pictures: |

|  |

| Yr ateb yn aml oedd cael llun addas o ffynhonnell arall er mwyn symud y golofn o destun i’r tudalen nesaf. | Often the solution was to get a suitable picture from another source in order to move the column of text to the next page. |

| Erbyn cyhoeddi Geiriadur Gomer i’r Ifanc yr oeddwn yn ymwybodol fod y cyhoeddwyr Dorling Kindersley wedi symud at CD Romau fel eu cyfrwng cyhoeddi a bûm yn gweithio gydag uned MEU Cymru’r Cyd-Bwyllgor Addysg i greu fersiwn CD-Rom o Geiriadur Gomer yr Ifanc. Yn anffodus, nid oedd y meddalwedd cyfrifiadurol oedd ar gael yn gallu dygymod â’r Gymraeg, yn enwedig felly drefn yr wyddor Gymraeg – rhywbeth eithaf pwysig mewn geiriadur! | By the time Geiriadur Gomer i’r Ifanc was published, I was conscious that the publishers Dorling Kindersley had moved to CD Roms as their publishing medium and I had been working with the Welsh Joint Education Committe’s Micro Electronics Unit (MEU Cymru) to create a CD-Rom version of Geiriadur Gomer yr Ifanc. Unfortunately, the computer software that was available wasn’t compatible with the Welsh language, and especially the order of the Welsh alphabet – something rather important in a dictionary! |

| Bu raid rhoi’r gorau i’r arbrawf, ond bu CBAC yn barod imi gael fersiwn digidol o’r gwaith a gyflawnwyd yn ystod yr arbrawf. | It was necessary to give up on the experiment, but the WJEC was prepared for me to have a digital version of the work which was completed during the trial. |

| Ar y pryd, yr oedd Nudd fy mab yn gweithio ym maes meddalwedd cyfrifiadurol. Y peth cyntaf a wnaeth oedd cynhyrchu meddalwedd oedd yn medru gosod geiriau yn nhrefn yr wyddor Gymraeg. Yr oedd hyn yn golygu bod modd datrys un o brif broblemau meddalwedd Cymraeg. | At the time, Nudd my son was working in the field of computer software. The first thing he did was produce software that was capable of arranging words in the order of the Welsh alphabet. This meant that there was a way to solve one of the main problems with Welsh-language software. |

| Ar ben hynny llwyddodd greu cronfa ddata oedd yn derbyn y gwaith digidol a wnaethpwyd dan nawdd CBAC. | As well as that he succeeded in creating a database which accepted the digital work which had been created under the auspices of the WJEC. |

| Y canlyniad oedd cronfa ddata eiriadurol unigryw. Rwy’n dal i ryfeddu at yr hyn sy’n bosibl ei wneud a hynny ar ôl pymtheng mlynedd o’i defnyddio. | The result was a unique lexicographical database. I am still surprised at what it can achive, even after fifteen years of using it. |

| • Dau eiriadur cynhwysfawr Cymraeg – Saesneg yn diffinio geiriau, a geiriadur Saesneg- Cymraeg - na fyddai’n bosibl mewn un llyfr, ac ar gael ar yr un dudalen • Cyfarwyddiadau yn eich dewis iaith • Meta-destun lle gallwch neidio at ddiffiniad unrhyw air mewn testun drwy clicio arno | • Two comprehensive Welsh – English dictionaries defining words, and an English – Welsh dictionary – that wouldn’t be possible in one book, and available on the same page. • Instructions in your language of choice. • Meta-text where you can jump to the definition of any word in a text by clicking in it |

| Ac y mae holl broblemau llyfr yn diflannu: • Dim problem trefn yr wyddor • Pob gair yn y geiriadur ar gael ym mhob ffurf dreigledig • Pob berf wedi’i rhedeg ym mhob Amser mewn dull ffurfiol ac anffurfiol • Llawer iawn o Ymadroddion, Priod-ddulliau a diarhebion a gallu dod o hyd iddynt drwy deipio i mewn unrhyw air arwyddocaol o’r ymadrodd • Brawddegau enghreifftiol • Geiriau cyfystyr • Yn cynnwys cyngor gramadegol ynglŷn â defnydd gair. | And all the problems of a book disappear: • No problem with alphabetic order • Every word in the dictionary available in every mutated form • All verbs conjugated formally and informally in every Tense • A large number of Phrases, Idioms and proverbs and the ability to find them by typing in any significant word from the phrase • Example sentences • Synonyms • Including advice on grammar together with the usage of a word. |

| Ewch i mewn i’r Gweiadur. Mae ar gael yn rhad ac am ddim, dim ond ichi gofestri trwy gyrru ebost at info@gweiadur.com. | Go into the Gweiadur. It’s available free of charge, you just have to register by email to info@gweiadur.com. |

|

|

| Dewiswch eich iaith yn y blwch ar frig y tudalen ac fe gewch chi bopeth y byddech chi’n disgwyl ei gael mewn geiriadur. | Choose your language in the box at the top of the page and you’ll get everything you’d expect to get in a dictionary. |

| Ni wn am unrhyw ffynhonnell ddigidol arall yn Gymraeg. Mae hwn yn gallu gwneud pethau nad ydyn nhw’n bosibl mewn cyfrol brint na chwaith mewn e-lyfr, e.e: | I know of no other digital source in Welsh. This can do things that aren’t possible in a print volume nor in an e-book, eg: |

| Teipiwch mrodyr i’r blwch gwag yn y rhestr eiriau • Cliciwch ar y chwyddwydr ar yr ochr • Cliciwch ar brodyr • Cliciwch ar brawd1 • Cliciwch ar y blwch i weld beth yw brawd2 a brawd3 | Type mrodyr into the empty box in the word-list • Click on the magnifying-glass at the side • Click on brodyr • Click on brawd1 • Click on the box to see the information for brawd2 a brawd3 |

| Teipiwch chewch i’r blwch gwag yn y rhestr eiriau • Cliciwch ar cewch • Cliciwch ar cael • Sylwch: cyngor gramadegol • Rhediad: yn rhedeg y ferf ym mhob Amser yn ffurfiol ac yn anffurfiol • Cliciwch ar y blwch Ymadroddion i weld 54 o ymadroddion | Type chewch into the empty box in the word-list • Click on cewch • Click on cael • Note: grammar advice • Conjugation: conjugating the verb in every Tense both formally and informally Click on the box Phrases to see 54 phrases |

| Teipiwch teselation i’r blwch gwag yn y rhestr eiriau: • Mae wedi’i gamsillafu Cliciwch ar tessellation • Os nad ydych chi’n gwybod beth yw ‘tessellation’ cliciwch ar ‘brithwaith’ ac fe gewch chi ddiffiniad Cymraeg • For English (a defnition of ‘tessellation’) see ‘Welsh’! Waw! | Type teselation in the empty box in the word-list • It’s been mis-spelled. Click on tessellation • If you don’t know what ‘tessellation’ is click on ‘brithwaith’ and you’ll get a Welsh-language definition • For English (a definition of ‘tessellation’) see ‘Welsh’! Waw! |

| Teipiwch stand • Cliciwch ar Ymadroddion | Type stand • Click on Phrases |

| Teipiwch ohonom: • Cliciwch ar o • Sylwch: yn rhoi cyngor gramadegol • Rhediad: yr arddodiad | Type ohonom: • Click on o • Note: giving grammar advice • Conjugation: the preposition |

| Teipiwch felen • Dilynwch y cadwyn • ‘Melyn’ Cliciwch ar Cyfystyron Saesneg | Type felen • Follow the chain • ‘Melyn’ Click on English Synonyms |

| Teipiwch codi’r rhastal; tin y nith; • Cliciwch ar runt i gael mwy o eiriau Cymraeg | Type codi’r rhastal; tin y nith; • Click on runt to get more Welsh words |

| Teipiwch Ffrancwr • Cliciwch ar ‘Wicipedia Cymraeg’ • Cliciwch ar Ffrainc • Ewch yn ôl a chliciwch ar Frenchman • Wedyn cliciwch ar Wikipedia (English) | Type Ffrancwr • Click on ‘Wicipedia Cymraeg’ • Click on Ffrainc • Go back and click on Frenchman • Then click on Wikipedia (English) |

Gweiadur.com

Yn nhermau llyfrau: geiriadur gwyddoniadurol dwyieithog cynhwysfawr

In book terms: a comprehensive bilingual encyclopaedic dictionary

Ond mae’n fwy na geiriadur: Adnau gwybodaeth ddigidol ddwyieithog

But more than a dictionary: a bilingual digital knowledge repository

Colofn 2, Gorffenaf 2018: Creu Geiriadur Gomer i’r Ifanc

| Geiriau a Geiriadura Dechreuodd fy nhaith eiriadura ym merw ad-drefnu Llywodraeth leol yn 1974. Crëwyd wyth sir fawr newydd, wyth gwasanaeth llyfrgell newydd, gydag wyth o lyfrgellwyr proffesiynol, yn gyfrifol am wasanaethau i blant a phobl ifanc. Yr oedd y rhain yn llyfrgellwyr yr oedd y rhan fwyaf ohonom wedi bod trwy Goleg Llyfrgellwyr Cymru a dod o dan ddylanwad y diweddar Frank Keys oedd yn arbenigo ym maes llyfrau plant. | Words and Dictionary-making My journey as a compiler of dictionaries began in the ferment of the local government reorganisation in 1974. Eight large new counties were created, and eight new library services with eight professional librarians, responsible for services to children and young people. They were librarians most of whom had been through the College of Librarianship Wales and come under the influence of Frank Keys, who specialised in the field of children's books. |

| Ffurfiwyd Cymdeithas Llyfrgellwyr Plant Cymru oedd yn awyddus i ddylanwadu ar y cyrff a oedd yn gyfrifol am lyfrau plant – Y Cyd-bwyllgor Addysg, Cyngor y Celfyddydau a’r Cyngor Llyfrau (nad oedd a chyfrifoldeb am lyfrau plant ar y pryd.) Bûm i’n ddigon ffodus i fod yn aelod o Banel Llenyddiaeth Plant Cyngor y Celfyddydau a ffurfiwyd gan y diweddar Meic Stephens – coffa da amdano. | The Society of Welsh Children’s Librarians was formed, which was keen to have an influence on the bodies responsible for children's books – the W.J.E.C., the Arts Council, and the Welsh Books Council (which was not responsible for children's books at the time). I was lucky enough to be a member of the Welsh Arts Council’s Children’s Literature Panel, which was created by the late Meic Stephens of blessed memory. |

| Un o dasgau’r panel oedd edrych am fylchau yn narpariaeth llyfrau plant y tu allan i faes addysg. Fel llyfrgellydd yr oedd gennyf ddiddordeb ym maes llyfrau ymchwil. Yr oedd Atlas Cymraeg ar gael, yr oedd y gwyddoniadur Chwilota ar y gweill ond nid oedd unrhyw eiriadur Cymraeg i blant. Yn wir, nid oedd yna unrhyw eiriadur cyfan oedd yn diffinio geiriau yn Gymraeg - yr oedd Geiriadur Prifysgol Cymru ar gael ond dim ond wedi cyrraedd y llythyren ‘G’ y pryd hynny. | One of the panel's tasks was to look for gaps in the provision of children's books outside the field of education. As a librarian I was interested in the field of reference books, The Welsh Atlas was available, the encyclopaedia Chwilota was on the drawing board, but there was no dictionary of Welsh for children. In fact, there was at that time no complete dictionary with definitions of words in Welsh – the University of Wales Dictionary was available but had only reached the letter 'G'. |

| Yn ysbryd brwdfrydig y cyfnod, dechreuais lunio geiriadur Cymraeg: 1. A fyddai’n diffinio geiriau Cymraeg yn Gymraeg 2. A fyddai’n ateb y cwestiynau yr oeddwn i, fel dysgwr, wedi cael trafferth i’w hateb. 3. Oedd yn cyflwyno gwybodaeth yn y ffyrdd yr oedd y geiriaduron Saesneg gorau i bobl ifanc yn eu gwneud. | In the enthusiastic spirit of the time, I began to draw up plans for a Welsh dictionary: 1) Which would define Welsh words in Welsh 2) Which would answer the questions which I, as a learner, had had difficulty in getting answers to 3) Which would present knowledge in the same ways as the best English dictionaries for young people were doing. |

| Bu’r Cyd-bwyllgor Addysg yn ddigon dewr i dderbyn y syniad (nid oeddwn yn athro, nid oeddwn yn ieithydd, nid oeddwn yn eiriadurwr – ond yr oeddwn yn frwdfrydig) a derbyniais ganddynt gymorth amhrisiadwy – golygyddion a’m cadwodd ar y llwybr cul a rhywun i osod yr holl ddeunydd ar brosesydd geiriau. | The W.J.E.C. were sufficiently brave to take on the idea (I was not a teacher, I was not a linguist, I was not a lexicographer – but I was enthusiastic) and I received invaluable support from them – editors who kept me on the straight and narrow and someone to word-process all the material. |

| Beth oedd y Geiriadur hwn felly? 1. Geiriadur Cymraeg cyfoes na fyddai’n cynnwys geiriau oedd wedi diflannu o’r iaith | So, what sort of Dictionary was this? 1. A dictionary of contemporary Welsh which would not contain words that had disappeared from the language. |

| 2. Geiriadur a fyddai’n gosod geiriau yn eu ffurf safonol na fyddai’n cynnwys ffurfiau tafodieithol ac ychydig o’r ffurfiau ansafonol mwyaf cyffredin | 2. A dictionary that would present words in their standard form and would not contain dialect forms, and would contain only a few of the most common non-standard forms |

| 3. Geiriadur a fyddai’n diffinio geiriau Cymraeg yn Gymraeg: • Nid yw Geiriadur Prifysgol Cymru yn gwneud hyn yn achos ymadroddion a geiriau cyfansawdd fel llygad y dydd; llygad maharen; llygad y geiniog; madruddyn y cefn • Nad oedd yn dibynnu ar restr o eiriau cyfystyr, e.e. lletchwith a trwsgl, trwstan, afrosgo, di-lin, anfedrus, bwngleraidd, chwithig, allan o le, annifyr, anffodus, annheg (GPC) • Oedd yn ceisio dweud beth oedd ystyr y gair mewn geiriau mor syml neu symlach na’r gair ei hun • A fyddai’n anelu at diffinio y geiriau a ddefnyddiwyd mewn diffiniadau • Geiriau Saesneg cyfatebol | 3. A dictionary that would define Welsh words in Welsh: • The University of Wales Dictionary does not do this in the case of phrases and compound words such as 'llygad y dydd' (the day's eye i.e. daisy, or poetically the sun), 'llygad maharen' (limpet), 'edrych yn llygad y geiniog' (to look the penny in the eye, i.e. to practise strict economy) and 'madruddyn y cefn' (the spinal cord) • Did not define a word in a list of synonyms e.g. 'lletchwith: trwsgl, trwstan, afrosgo, di-lin, anfedrus, bwngleraidd, chwithig, allan o le, annifyr, anffodus, annheg (GPC)' – (note: all these words used to define 'lletchwith' are simply synonyms meaning awkward, clumsy, inexpert) • Tried to give the meaning of the word in words as simple or simpler than the word itself • Would aim to define the words which were used in definitions • Would give equivalent English words |

| 4. Geiriadur a fyddai’n dangos yr holl ffurfiau Cymraeg nad oeddwn i wedi gallu eu ffindio: • Ffurfiau lluosog enwau dagrau; ceir; cŵn; elyrch • Ffurfiau berfol erys; cer; saf • Ffurfiau ansoddeiriol braith; gwleb; gwlypach • Ffurfiau’r arddodiaid amdanaf fi; amdanat ti; ohonof fi; ohonot ti | 4. A dictionary which would show all those Welsh forms which had not been easy for me to find: • Plural forms of nouns: dagrau (tears); ceir (cars), cŵn (dogs); elyrch (swans) • Verb forms: erys; cer; saf • Adjectival forms braith (feminine of brith, speckled); gwleb (feminine of gwlyb, wet; gwlypach (comparative of gwlyb, wet) • Prepositional forms such as amdanaf fi; amdanat ti; ohonof fi; ohonot ti |

| 5. Geiriadur a fyddai’n cynnig cyngor gramadegol: • Rhestr o’r geiriau sy’n achosi treiglad • Sylwch: ni ddefnyddir ‘y’ gydag enwau afonydd • Mae ‘amryfal’ yn arfer dod o flaen enw • Defnydd er, ers, erioed | 5. A dictionary which would offer grammatical advice, for example: • A list of words causing mutation • Note: 'y' is not used with the names of rivers • 'Amryfal' (various) usually comes before the noun • The use of er, ers, erioed |

| 6. Geiriadur a fyddai’n cynnwys pethau gorau geiriaduron Saesneg: | 6. A dictionary which would contain the best features of English dictionaries: |

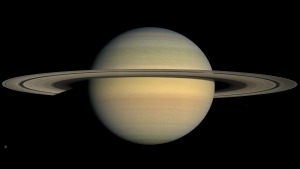

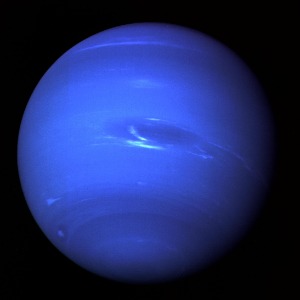

| 7. Lluniau • Du a gwyn a lliw • Wedi’u tynnu i raddfa yn dangos maint cymharol pethau • Yn dangos teuluoedd: gwartheg, defaid, ceffyl, ymlusgiaid etc. • Teulu • Cysawd yr Haul • Elfennau Cemegol • Cytser • Cyfandiroedd a’r Cefnforoedd • Y Corff • Ffrwythau • Pysgod • Adar • Coed • Blodau • Baneri’r byd • Lliwiau | 7. Illustrations • Black and white and colour • Drawn to scale showing the relative sizes of things • Showing word families: cattle, sheep, horses, reptiles etc. • Members of the family • The Solar System • Chemical Elements • Constellations • Continents and Oceans • The Body • Fruits • Fishes • Birds • Trees • Flowers • Flags of the world • Colours |

| 8. Atodiadau • Rhifau Prifol; Trefnol; Ffracsiynau • Arian – sut i’w ysgrifennu • Pwysau • Mesur • Buanedd | 8. Appendices • Cardinal numbers; ordinal numbers; fractions • Money – how to write it • Weights • Measures • Speed |

| 9. Adran Saesneg -> Cymraeg | 9. An English -> Welsh section |

| Cyhoeddwyd Geiriadur Gomer i’r Ifanc ym 1994 a phethau sy’n taro dyn, yw: 1. Fel yr ydych yn meddwl eich bod yn llenwi bylchau, fe welwch yn gliriach y bylchau sydd ar ôl 2. Yr ydych yn dysgu llawer o bethau yr hoffech chi eu gwneud yn well y tro nesaf 3. Does dim un geiriadur Cymraeg arall sy’n cynnig yr un ystod o wybodaeth â’r hyn a welwch chi uchod. | The Geiriadur Gomer i’r Ifanc was published in 1994 and what strikes one now is: 1. As you think you are filling in the gaps, you see more clearly the gaps that remain 2. You learn a lot of things that you hope you will do better next time 3. There is no other Welsh dictionary which offers the same range of knowledge as you see above. |

gomer.co.uk/geiriadur-gomer-ir-ifanc.html

Colofn 1, Gorffenaf 2018: Trosolwg o fy llyfrau / Overview of my books

| Wrth lunio Geiriadur Gomer i’r Ifanc yr oeddwn yn ceisio ateb y problemau yn Gymraeg yr oeddwn yn gwybod amdanyn nhw. Ond wrth ddechrau gyda phroblemau yr wyt ti’n gwybod amdanyn nhw, rwyt ti’n cyrraedd y problemau nad oeddet ti’n gwybod amdanyn nhw. | In creating Geiriadur Gomer i’r Ifanc (the Gomer Young People's Dictionary) I was trying to address the problems in Welsh that I knew about. But when you begin with the problems you know about, you arrive at the problems you didn't know about. |

| Y Treigladau yw un broblem fawr. Mae yna lyfr safonol sy’n ymdrin â’r treigladau Y Treigladau a’u Cystrawen. Mae’n waith ysgolheigaidd o’r radd flaenaf, ond yr oedd angen rhywbeth llawer symlach arnaf fi. Yr ail broblem oedd bod pob llyfr gramadeg yr adeg honno yn rhestru’r un rheolau treiglo ond yn gadael yr un bylchau heb eu hegluro. | The Mutations are a big problem. The standard book that deals with mutations is Y Treigladau a’u Cystrawen. It is a first-rate work of scholarship, but I felt the need for something much simpler. The second problem was that every grammar book at that time listed the same mutation rules but left the same gaps without explaining them. |

| Wrth fynd i’r afael â’r treigladau yn y Geiriadur, dysgais ddau beth: 1. Mae pob un o’r treigladau ac eithrio Treiglad Meddal yn cael ei achosi gan air arbennig - lluniais restr o’r geiriau hynny 2. Bod angen mwy o le nag oedd yn y Geiriadur i fynd i’r afael â Threiglad Meddal. | In getting to grips with the mutations in the Dictionary, I learnt two thing: 1. Every one of the mutations apart from Soft Mutation is caused by a particular word – I created a list of those words 2. To tackle the Soft Mutation needed more space than was available in the Dictionary. |

| Y canlyniad oedd Y Treigladur: A Check-list of Welsh Mutations. Dyma rai o’r pethau nad oeddwn i’n gwybod, e.e. • Does dim ‘h’ ymwthiol yn dilyn eich (ein hathro; eu hathro ond eich athro) • Mae nifer o wahanol dreigladau yn dilyn ‘un’ yn dibynnu a yw un yn rhifol, enw, neu ansoddair • Nid yw graddau cymhariaeth yn achosi treiglad o flaen enw cystal pêl-droediwr; gwell mam • A phethau mwy egsotig fel pryd mae bod yn treiglo, y tair tew; robin goch; foneddigion a boneddigesau - y cewch chi atebion iddyn nhw yn Y Treigladur. | The result was Y Treigladur: A Check-list of Welsh Mutations. Here are some of the things I didn't know, for example: • There is no intrusive 'h' following eich (your): (ein hathro; eu hathro ond eich athro) • There is a number of different mutations following 'un' depending on whether un is a numeral, noun or adjective • Comparative degrees of adjectives before the noun do not cause mutation: cystal pêl-droediwr; gwell mam • And more exotic things like when bod mutates, y tair tew; robin goch; foneddigion a boneddigesau – you get the answers to them in Y Treigladur. |